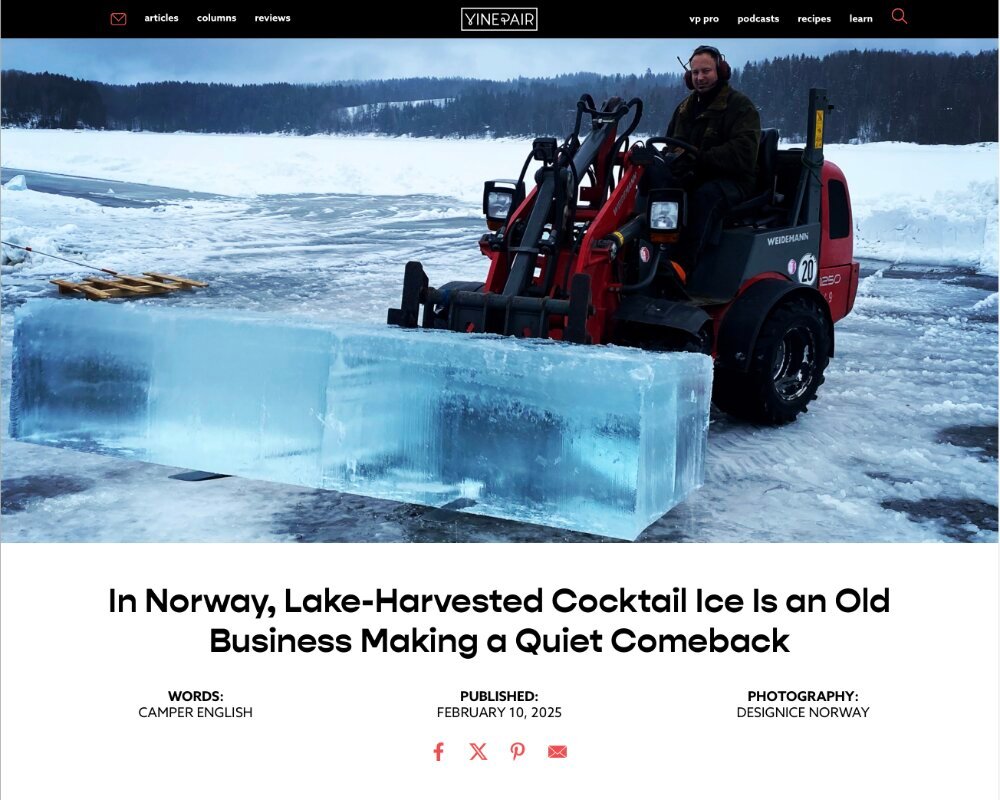

In the story I wrote for Vinepair about harvesting lake ice in Norway, a couple sections got cut out. They weren’t essential to the story, but I liked them a lot!

This first section is about ice blocks – I was researching the blocks people use at different ice hotels and ice carving festivals to see if they were machine or nature-made. The results are fascinating:

Other Lakes, Other Places

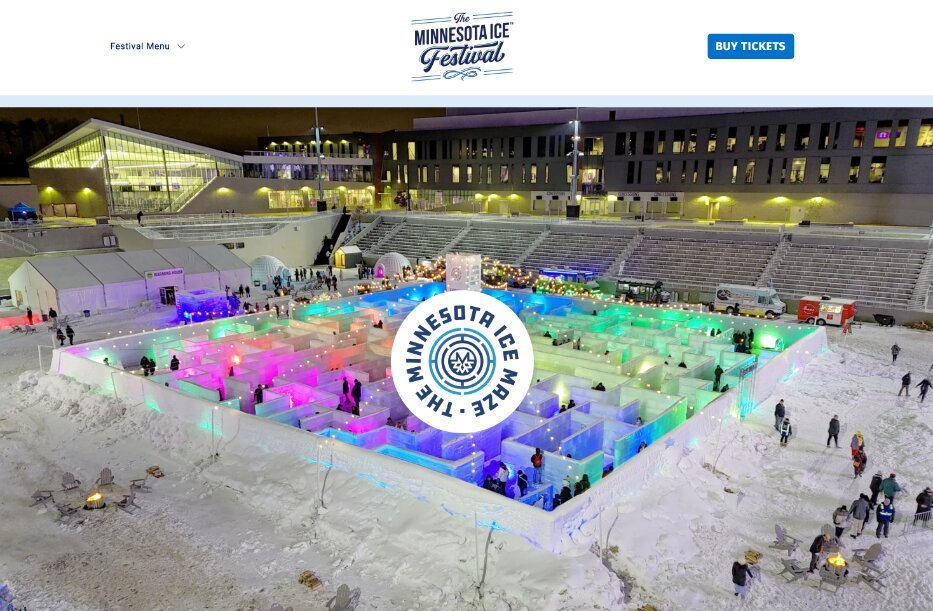

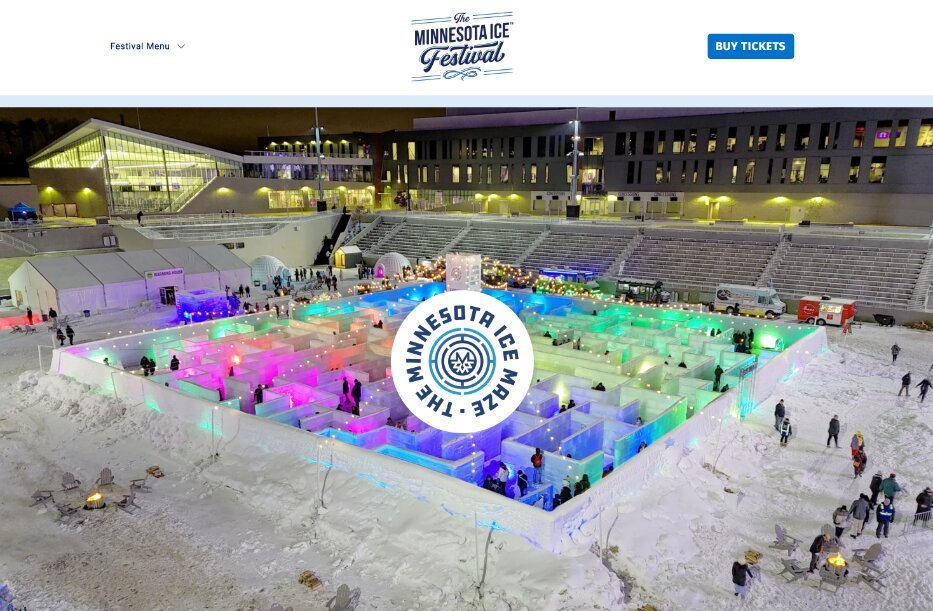

Not all ice blocks are equal. The Minnesota Ice Festival this year features the world’s largest ice maze, with all the 3,452, 425-pound blocks for it produced by a fast (and semi-clear) brine-cooled block-making machine owned by Minnesota Ice.

Orderud of DesignIce in Norway says that the blocks for a lot of other ice mazes and ice hotels (the non-see-through parts anyway) are typically made from compressed snow, rather than ice. Clear Clinebell blocks are sometimes used for the windows.

The Songhua River is the source for “most” of the thousands upon thousands of ice blocks used for the huge annual Ice and Snow Festival in Harbin, China, not too far from the northern border with Russia. Reportedly there are more than 2000 sculptures and constructions in the theme park built from ice or snow, and some of the ice structures reach over 150 feet in height.

And at the World Ice Art Championships, held annually in Fairbanks, Alaska, blocks are taken from gravel ponds and standardized to 6 by 4 by about 2.5 feet (depending on how thick the ice is that year). Leigh Anne Hutchison, member of the Ice Alaska Board of Directors, says of the pond blocks, “Some even are cool enough to have methane bubbles in them.”

That sounds a bit more “scary” than “cool,” until you realize that nobody is trying to eat that ice. (The blocks with methane bubbles do look pretty groovy though; she sent me pictures.) As far as Orderud is aware, none of the naturally frozen ice for these or any other festivals is served in drinks.

Read the story on Vinepair here, and imagine this section in it.