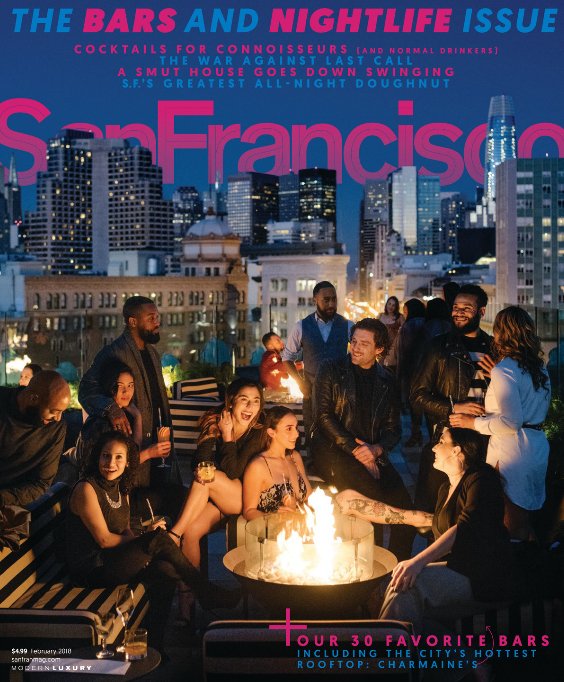

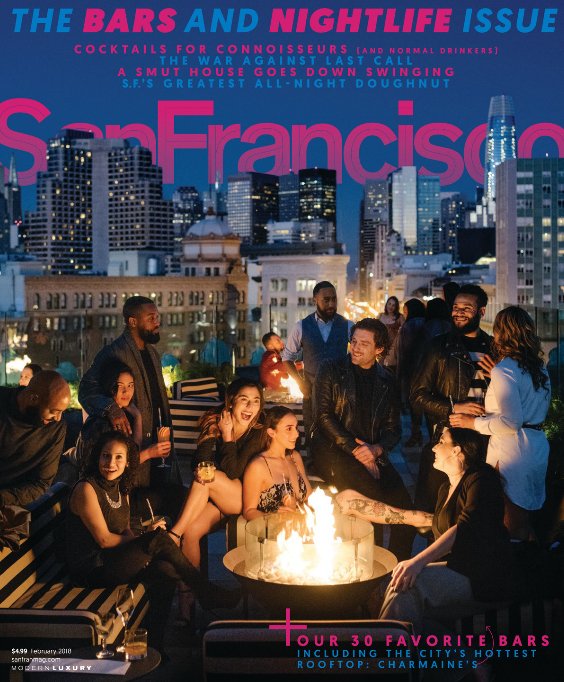

It has been many years since I have contributed to San Francisco Magazine, but now I'm back! In the new February Bars & Nightlife issue, I have ten stories loosely themed around "Future proofing the cocktail: How Bay Area drink makers are reinventing our favorite alcoholic beverages."

It has been many years since I have contributed to San Francisco Magazine, but now I'm back! In the new February Bars & Nightlife issue, I have ten stories loosely themed around "Future proofing the cocktail: How Bay Area drink makers are reinventing our favorite alcoholic beverages."

Below is the intro with links to all ten stories and brief intros from me.

Two decades into the Bay Area’s cocktail awakening, you’d think that bars would have settled into a comfortable middle age—the imbibing equivalent of staying home to Netflix and chill. But you’d be wrong.

Creativity stirs all over the region, and drink makers and bar owners continue to spin out new ways to stay relevant and keep us guessing: with secret menus, popup concepts, and menu launch parties; with vibrant drinks, exotic ingredients, and bar-specific spirits; with quality concoctions served at double the speed, thanks to newfangled juices and outsourced ice. And to meet the expanding demand for quality, novelty, and expediency in booze consumption, new clusters of great bars have sprung up not just in the East Bay but also to the north and south. These changes are often nuanced but pervasive, taking place across many bars in many precincts throughout the ever-thirsty Bay Area.

Scanning the cocktail horizon, you can spot the big ideas and the small revisions that are changing the way we drink in 2018 and beyond. Here are 10 of them.

Bartenders Are Going Straight to the Source

How bartenders are directing spirits creation from distillers.

Forget The Simple Description: These Are Very Complicated Cocktails

A look into the mind of Adam Chapman from The Gibson.

Wine Country Has An Unofficial Cocktail AVA

Drinks at the fantastic Duke's and other Healdsburg cocktail bars.

The Future (and Present, Actually) Is Female

Who runs the bars? Girls. A sampling of ten women running things in Bay Area Bars.

Asian Restaurants Are the Center of Cocktail Innovation

Once the home of sake bombs and soju immitations of real drinks, now Asian restaurants are some of the most forward-looking.

Viking Drinks Are So Hot Right Now

Aquivit will be everywhere in 2018.

You'll Be Spending the Night in San Jose

Paper Plane and other great bars in San Jose.

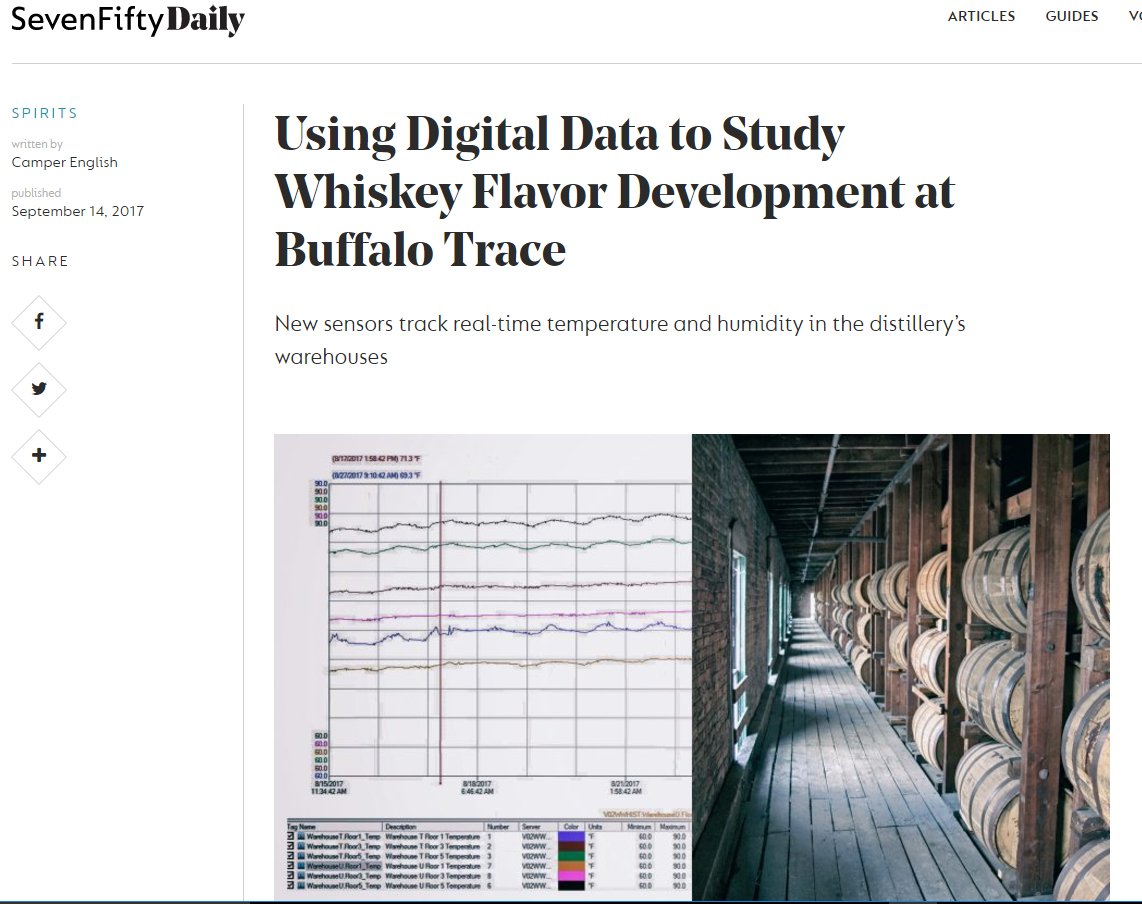

Your Highball Intake Is About to Increase Dramatically

Whiskey and other highballs are happening.

Outsourcing Is In

Blind Tiger Ice and Super Jugoso are going to have a major impact on prep work in SF bars.

The Mission Has Only Just Begun

So, so many new bars are opening in the Mission District.

I've already got my next assignment for San Francisco Magazine, so hopefully this will be a regular thing.