I have been writing a series of blog posts about cognac, and I've really been looking forward to this one about "early landed" cognac.

This series has been detailed information about cognac production generally, and Hine cognac specifically, as I was able to ask the cellar master Eric Forget a ton of questions. It has been a fun way for me to review what I know, challenge my assumptions, and put together general production information with specifics from one brand.

The posts in this series are:

1. Cognac from grapes to wine.

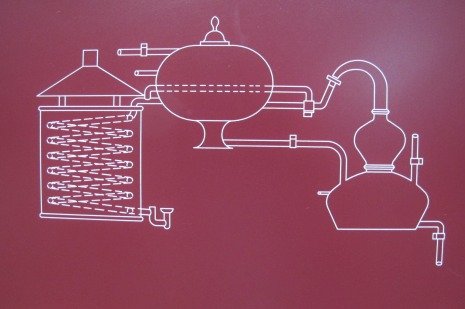

2. Cognac distillation and the impact of distillation on the lees.

3. Wood and barrels used for cognac.

4. Aging conditions for cognac.

5. The strange exception of early landed cognac.

6. Dilution and Additives in Cognac.

What the Heck is Early Landed Cognac

Early landed cognac is cognac that ages in Britain rather than in France. WHAT?? Yeah, it's weird because cognac is of course an AOC product, an Appellation d'origine contrôlée, like certain cheeses and rhum agricole and calvados and armagnac. Generally AOC products must be produced within a delimited region with a whole lot of rules for quality, and packaged in that region also.

So for there to be an exception in the AOC for cognac to be aged elsewhere and still able to be called cognac is wild.

The expression comes from the phrase "early landed, late bottled" meaning that they land on British shores early but aren't bottled until later. (In reality all cognac is aged so it's all late-bottled.)

To understand how this came to be, consider that a huge audience for cognac has always been Britain – and many of the cognac houses including Hine have British origins. In days before bottles were common, wine and spirits were shipped in barrels to the UK (thus beginning the tradition of scotch whisky being aged in ex-sherry barrels), and bottled there, so probably early landed cognac was once common. Today however not so much!

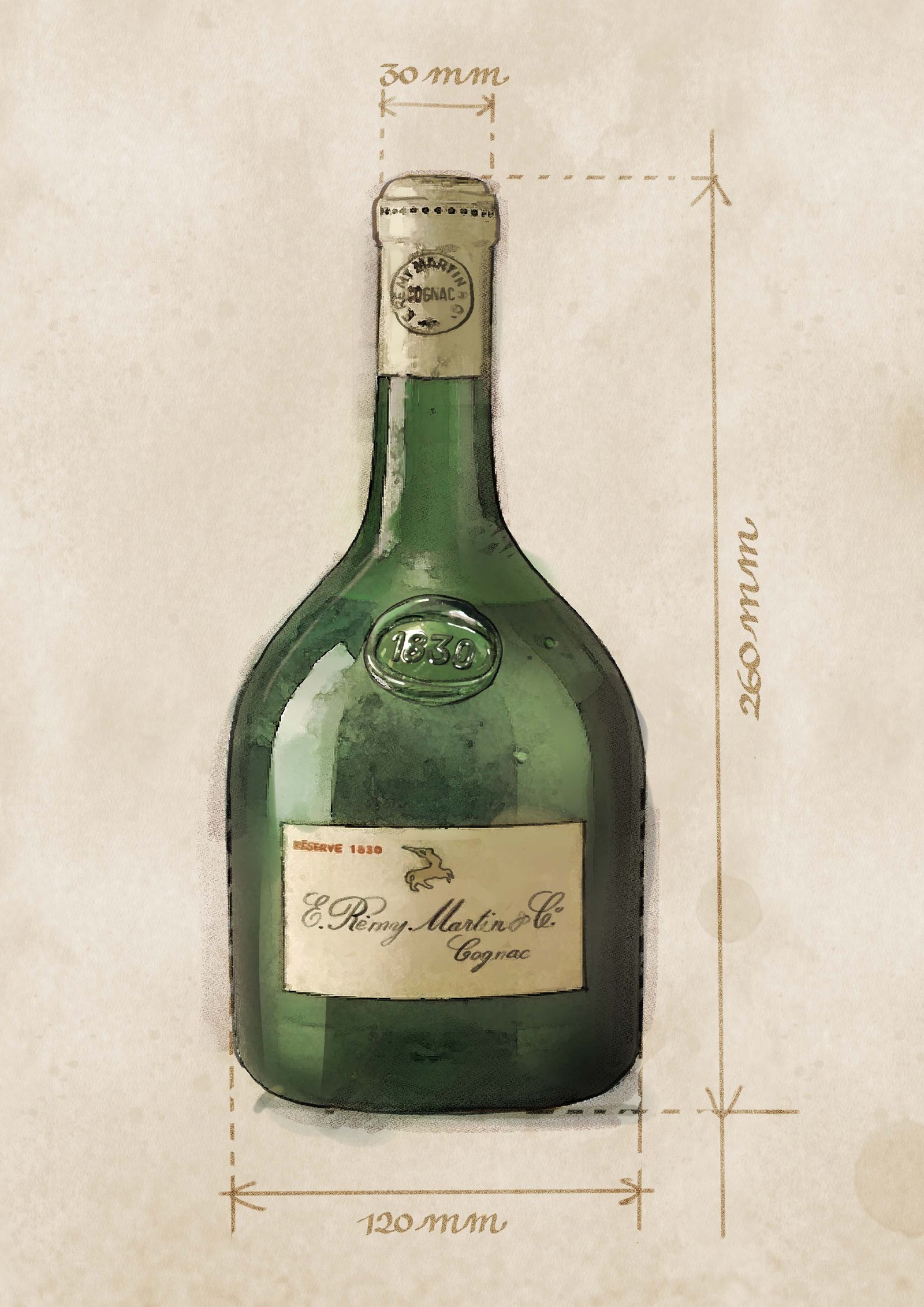

But early landed cognac is a specialty of Hine – when I looked up some information about it, every single story about early landed cognac is a story about Hine in particular. Currently on the brand's website, they list vintage 1975, 1981, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, and 1987 of early landed cognacs available for sale.

According to the Berry Brothers & Rudd website, "This custom [or early landed] dates back to the 19th century, when they first shipped selected vintage Grande Champagne Cognacs in cask to Bristol, in England."

photo: Olivier-Löser

History of Vintage and Early Landed Cognac

Hine offers vintage cognacs – both regular and early landed versions. Vintage cognac on its own is not very common- most all cognac is a blend of ages. And in fact vintage cognac was not legal to sell for about 25 years, according to this article from 1994 in the LA Times.

According to that LA Times story, early landed cognac was a way to sell vintage-dated cognac before it became legal again. "However, the BNIC [the cognac bureau] ruling only prohibited bottling of vintage-dated Cognac by the Cognac producers themselves. It didn’t stop the long-established practice of sending vintage-dated barrels of Cognac to England, where it was known as “early landed” Cognac. After varying periods of barrel-aging, English wine merchants would bottle this Cognac with a vintage year."

According to this post about cognac regulations, "In 1962 single vintage cognacs were banned. A few exceptions were made: early landed cognacs (these were ageing in England) and three cognac houses who held a perfect registration and could prove the provenance regarding year and district of their eau-de-vie. These three were Croizet-Eymard, Delamain and Hine.

In 1987 this ban was lifted again."

If true (not all info on the site is accurate so I'm trying to fact-check this), that would be a pretty cool historical factoid for a couple specific brands to get an exception.

Anyway – I mentioned that Hine offers both vintage and early landed cognacs but even better – they offer some of them from the same years so you could do taste comparison if you can get hold of them. There are vintages of both early landed and French-aged cognac from 1975, 1983, and 1985-1987. It would be amazing to taste them against each other.

Early Landed – How Hine Does It

Early landed cognac is distilled in France and sent to England to age "shortly after distillation." I first asked questions about how Hine ages their early landed cognacs, which made me curious about how other brands do it and what the regulations are. Those are below.

In the case of Hine, according to cellar master Eric Forget, the cognac for early landed is not produced any differently than it is for other vintages. It remains in the UK aging for about 20 years. Hine does not own the UK warehouses – they are "bonded warehouses". ("It is a British bond," Forget says.) The aging cognac is still owned by Hine while it's overseas.

I asked Forget if there are cellarmasters on site in England, and he replied, "We are fully in charge. The early landed just sleeps in the UK. There is no work during the time they spend there." So no manipulation is done to the cognac (transfering to different barrels, etc) – this is just a different aging environment, and then the barrels return to France afterward for bottling.

After aging in the UK, the cognac is sent back to France where it is bottled by Hine.

Early Landed Cognac Rules and Regulations

“The Bureau National Interprofessionnel du Cognac (BNIC) is a coordination and decision-making body for the Cognac industry." I reached out to them, via their PR agency, with some questions about the legalities of early landed and boy did I learn some new stuff! My impression of how early landed cognac is legal with the AOC was totally wrong.

Here is my email interview:

1. Can early landed cognacs be bottled in the UK or must they return to France for bottling?

2. If not, are they still legally cognac if bottled in the UK?

In respect of Cognac product specification, as homologated by French decree n° 2015-10 of January 07, 2015, there is no mandatory bottling in the delimited area. Therefore, it is possible to bottle Cognac in the UK, as soon as long as it has been aged for a minimum of 2 years in the delimited area.

3. If they are able to be bottled in the UK are there any special regulations – maybe something on dilution or additives that's different?

Regardless of the location, bottling has to respect the same rules, inside or outside the delimited area. Any addition not expressly referred to in Cognac product specification is strictly forbidden.

4. I believe in the past that people could buy a barrel and age/bottle it in England with an independent bottler/merchant like Berry Brothers – so people could have a private barrel. Is this still the case? (the bottom of this story from 2001 mentions doing it but I'm not sure if this has changed. )

In respect of Cognac product specification, it is possible to age cognac outside the delimited area but only if ageing during the first 2 years takes place in the delimited area.

5. Or must an approved Cognac brand do the bottling?

At this stage there is no approbation of bottlers by BNIC.

6. Are there any regulations on time of aging in the UK? (Min/max time – I see a lot of mentions of 20 years but don't know if this is something official)

To be directly sold to consumers, the only regulation is that cognacs aged at least 2 years. There is no maximum limit to this ageing, whether inside or outside the delimited area.

7. Are the cellars in the UK owned by the brands or are they independent?

It is up to the brands to decide how they want to organize the process.

So that's super interesting: 2 years is the minimum aging of cognac for VS, and after a cognac reaches that age it can be aged anywhere and bottled anywhere as long as it follows the rules of bottling for cognac.

Also interesting is that most cognacs are aged in a new oak barrel for the first several months of their life (8 months at Hine), which means that the cognacs are already on their second barrel before they get sent to the UK.

This was so new and interesting to me that I emailed Hine to clarify that it was actually the case that they're aged for 2 years. A contact at Hine (I'm not positive who) responded with the following (slightly edited for clarity):

Early landed used to be aged in Bristol, they are now aged in Scotland (and have been for a decade).

In the past, when tradition was that wines, cognacs or port were sent in cask to their final destination for commerce, liquids used to be bottled by the merchant it was sold to (Berry Brothers & Rudd, Corney & Barrow, etc. ).

This has completely stopped to avoid any possible fraud or problem during bottling that could damage the liquid, and furthermore, the brand.

Early landed are aged for around 20 years in the UK, after having spent the mandatory 2 years aging in Jarnac to obtain the Cognac appellation. Our cellar masters (Eric Forget and Pierre Boyer) travel to the UK every other year to taste the barrels on site. They last visited Scotland in June 2019.

After 20 years, barrels are shipped back to Jarnac in their bonded casks to be put in demijohns. They are then bottled at Hine, on demand.

This helps explain why you don't see a lot of early landed cognac lining shelves – they're such niche products that they're only bottled when needed. (In Sacramento, the Corti Brothers store specializes in this segment.)

photo: CK Mariot

Impact of Aging Cognac in England

In the last post in this series we talked about the impact of aging in wet versus dry cellars in Cognac. Well in the case of early landed its the case of wet vs wet-and-chilly. Hine vintages in France are aged in wet cellars. Forget says, "The difference comes from the difference in humidity and a low but stable temperature in UK."

The always-wonderful Dave Broom wrote about Hine and early landed cognac in 2001. Even the title is great! "Pale beauties that thrive in the dark."

We exit from the creaking lift into a chilly, crepuscular dungeon. A greenish-grey mould covers the walls like diseased cotton wool, barrels lie apparently smothered in soot, and the floor is slippery. Hell for a homeowner, but paradise for ageing Cognac that thrives in the cold and the humidity already seeping into my bones. These conditions help give early-landed Cognac its signature style…

He pulls samples from the casks, giving me a quick history lesson on how "early landed" means the spirit arrives here before it is two years old and how, when the style was more common, wine merchants would age it in waterside bonds in London, Bristol, Liverpool and Leith… [note: we see here before the law changed it was moved from France before it was 2 years old]

The pale colour, he explains, is because the humidity allows the strength of the spirit to fall, but the cold means there is virtually no evaporation.

The Berry Brothers website continues from the above:

Nowadays, Hine still ships some of its single vintage cognacs to the UK (and is one of a very rare few estates who continue this tradition) after they have spent several months ageing in new oak barrels in Jarnac.

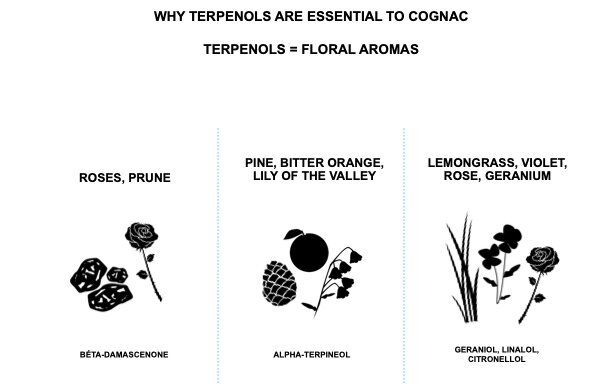

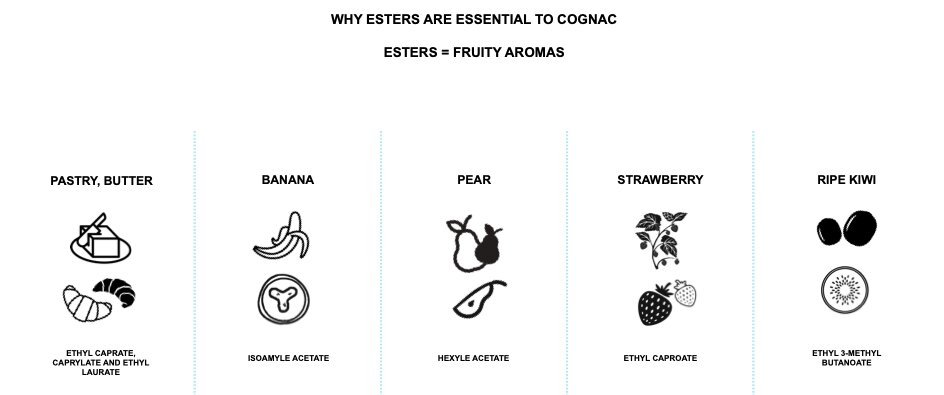

Cool, dark cellars house barely a hundred barrels of Early Landed (a barrel is the equivalent volume to around 350 bottles). Here the ageing conditions are quite different from those in Jarnac as the temperature is low and remains constant (between 8 and 12°C) and the high humidity level rarely drops below 95%. These factors ensure that Hine's Early Landed cognacs are particularly light and fruity with very delicate oaky notes, and delightful aromas of fresh flowers and the characteristic orange peel – very close to the cognac’s initial notes.

Nicholas Faith in his book Cognac describes the British palate as preferring this particular style of cognac. He writes:

This is why the brandies are lighter and mature more quickly than those which remain at home- indeed they are smooth, elegant, and delicious after a mere twenty years. This was much to the taste of old-style English connoisseurs. One of their breed, Maurice Healy, described such a cognac as 'of almost unearthly pallor and a corresponding ethereal bouquet and flavor'. By contrast they were – and -are- not overly highly rated by many French blenders, who find them flabby.

The low, stable temperature means there isn't a ton of wood impact on the spirit (as the light color indicates). Forget describes the taste difference of early landed cognacs, "The cognacs keep more freshness and liveliness and get this so typical orange peel nose and taste."

Conclusion

Early landed cognacs could be a marvelous opportunity to make an exact comparison of the aging environment on spirits. Currently they're aging in the UK, and you could compare Hine's vintage cognacs aged in France versus those in the UK.

And since there's that new 2015 law, cognac could be aged in other parts of the world too. I hope someone is doing so already because I'd like to try it in another decade or two when it's ready.

Note: This series of posts has been sponsored by Hotaling & Co, importers of Hine cognac.

photo: CK Mariot