I received an email from a newish soju brand Tokki Soju with a really interesting story. Given the technical skill of one of the founders, I thought I could get some additional information, and that's just what happened.

First, the background:

The brand was launched in 2016 by Founder Brandon “Bran” Hill and CEO Douglas Park and currently includes two soju offerings in its portfolio: the White Label (23% ABV) and the Black Label (40% ABV).

Armed with a BS in Molecular Biology, Tokki Founder Brandon “Bran” Hill moved to South Korea in 2011 to study traditional Korean fermentation and distilling. After receiving a Masters in Korean Traditional Alcohols at Susubori Academy, and having put some time in at a Korean yeast bank, he returned home to become the Head Brewer for Van Brunt Stillhouse in Brooklyn, NY. While at VBS, Bran began distilling soju as a passion project, and by 2016, the first bottles were hitting the shelves of NYC liquor stores.

What Is Soju and How is Tokki Different

Soju is a Korean distilled spirit that was traditionally made with rice, however during the Korean War, when rice was banned, most soju producers were forced to switch to alternative starches like wheat, sweet potatoes and tapioca. Although the ban was lifted in the 1990’s, many of the best selling brands in Korea still use alternative starches and chemicals to replicate the taste. Tokki Soju is the first American small-batch rice soju. Tokki is made with glutinous (“sticky”) rice, water, yeast and nuruk.

Soju is not to be confused with other Asian spirits, including Shochu and Sake (both of which hail from Japan), although there are some overlapping similarities to note. For instance, all three are made from rice, however both Soju and Shochu are distilled (while sake is brewed). Shochu and Sake are made with koji (inoculated rice), while Soju is made from rice. Most mass Soju and Shochu brands are distilled from alternative starches, including barley, sweety potatoes, wheat, etc. – but Tokki remains one of the few that uses rice, and again, glutinous rice at that.

What sets Tokki apart is that it’s the only soju brand on the market that uses glutinous (sticky) rice in the distilling process. They also hand-cultivate their own nuruk starter (a labor-intensive and costly process).

Nuruk for Soju Versus Qu for Baijiu

Nuruk is a traditional fermentation starter meant to saccharify the rice – most soju producers do not use the traditional ‘nuruk’ starter due to the intensive labor and costs. Tokki uses hand-cultivated nuruk that takes 2-3 weeks to grow. Tokki is distilled in a copper pot still and only 35% of the run is bottled. As for the sticky rice that Tokki sources, it is all local from Chungju, where the distillery resides, and as a result, will over time have a positive effect on the local agriculture as Tokki becomes the number one purchaser.

Nuruk in Korean alcohol seems similar to qu for Chinese spirits. I wrote about qu after a visit to China:

Qu is a combination of mold, yeast, and bacteria. It is used not only for baijiu production but also for undistilled Chinese beverages.

- The mold we could say is similar to koji used in sake and shochu production. It helps break the starches in the grains down into fermentable sugars (saccharification). In whiskey, this is accomplished by adding malted barley and/or enzymes to the grains.

- The yeast makes alcohol, as it does in other spirits.

- The bacteria helps in flavor development of the alcohol.

Back to nuruk: According to Wikipedia, "Microorganisms present in nuruk include Aspergillus oryzae, Rhizopus oryzae, lactic acid bacteria such as Lactobacilli, and yeasts, predominantly Pichia anomala and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Aspergillus provides the enzyme amylase, which saccharifies the rice's starches. The resulting sugars are consumed by the yeasts, producing alcohol, as well as the Lactobacilli, producing lactic acid. Rhizopus provides the enzyme protease and lipase, which break down the protein and fat in the outer layers of the rice grain (endosperm), allowing the amylase access to the starches in the inner part.

Back to nuruk: According to Wikipedia, "Microorganisms present in nuruk include Aspergillus oryzae, Rhizopus oryzae, lactic acid bacteria such as Lactobacilli, and yeasts, predominantly Pichia anomala and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Aspergillus provides the enzyme amylase, which saccharifies the rice's starches. The resulting sugars are consumed by the yeasts, producing alcohol, as well as the Lactobacilli, producing lactic acid. Rhizopus provides the enzyme protease and lipase, which break down the protein and fat in the outer layers of the rice grain (endosperm), allowing the amylase access to the starches in the inner part.

Camper: Can you name any differences in composition/action of nuruk vs qu, and also any production differences if you know?

Brandon “Bran” Hill:

Yes, traditional nuruk is similar to qu or "big qu" as far as the method of cultivation and how it is used in a fermentation, as a saccharification enzyme. Qu is different than what we personally use, because qu has wild yeast strains and bacteria attached to it. We only want aspergillus oryzae in our nuruk for conversion purposes and consistency. So, in our case, our nuruk is more similar to koji production, except koji is cultivated on whole rice and nuruk uses milled wheat cakes.

Camper: For other brands that use "alternative starches" and don't use nuruk, do they just add enzymes? (I see on Wikipedia that many/most mass market sojus are distilled to vodka levels then just diluted so probably!)

Bran:

The mass produced sojus brands (green bottle soju) do not make their soju. They operate more as bottlers of mass produced neutral spirit (like vodka) that they purchase and then add sweeteners, chemicals, and dilute before bottling. I currently do not know another soju brand that uses traditional nuruk, but not to say they don't exist, but it is rare. Brands who make their soju today, often use Japanese koji in their fermentations.

Fermentation

Korean Fermentations with sticky rice and nuruk purely depend on what you are trying to do with the fermentation. There are no set times for Korean fermentations and many different styles. Lots if variables come into play that will effect what determines the end of the fermentation. For example, the style or method used to start the fermentation process, feeding the culture multiple times, temperature of the fermentation, desired attenuation of the ferment, etc. Our fermentations take about 9 days for what we are trying to accomplish.

Sticky Rice

Camper: Sticky rice – from a production standpoint, why sticky rice? Wikipedia says "Glutinous rice is distinguished from other types of rice by having no (or negligible amounts of) amylose, and high amounts of amylopectin (the two components of starch)." and that amylose is "hard to digest" – does this imply that fermentation with nuruk would be much easier with sticky rice than with traditional rice as amylose is harder to break down from starch into fermentable sugars? I'm kind of making a guess here.

We tested many types of rice and combinations of rice in the beginning of Tokki, when we were deciding on a recipe. We choose to use just sticky rice or more specifically Korean Chap Ssal (잡쌀) for a few reasons. First, we knew wanted to use a Korean variety of rice for our soju. Second, for quality the flavor. Sticky rice is more glutinous and has a much sweeter and rounder flavor and feel that we prefer over other varieties of rice.

Yes, nuruk does break down the starch and into fermentable sugars to aid the start of the fermentation process. We also pitch yeast after our nuruk is added. It is true that amylose is harder to breakdown than other starch structures, but with our practices, I personally have never had a problem with liquefaction, conversion, or hitting desired attenuation in our fermentations with sticky rice. Also, I would not say that nuruk breaks down sticky rice easier than regular rice varieties in my experience. I have had great results with nuruk applied to both types of rice and haven't personally noticed a big discrepancy favoring one over the other as far as speed and yield of the fermentation goes.

By "hard to digest" amylose as a resistant starch on the Wikipedia page, I think they are referring to human digestion and not yeast digestion.

Humans have a problem physically digesting amylose when eating cereal grains because its molecular structure, but when we are mashing we break down the polymer and then distill it. The end soju product does not have the same molecular structure so, doesn't effect human digestion the same way. Also, haven't had any issues with yeast propagation in the fermentations either, but like you said…sticky rice has small amounts of amylose.

Camper; Also, is there a taste difference between using sticky and traditional rice? If so, how would you describe that difference?

Yes, as I said above, sticky rice is more glutinous and has a much sweeter fuller flavor that translates to the distillate. We preferred this flavor and thought it was much more versatile for our product when pairing. Most other rice varieties, like Korean Meb Ssal (멥쌀) lack sweetness and are more dry, flat, and less complex when distilled.

Why These ABVs, and Why Two Versions?

Camper: Bottling at two ABVs – In Korea what is the standard ABV (if there is one) – the lower or higher proof? If one or the other is standard (I think the lower proof), why did you decide to release it at two proofs in the US? I've noticed that some shochu brands have started doing this, I think to appeal to the bartender/mixology set.

Traditional soju in the past was consumed a high abv, usually whatever it came off the still at or slightly diluted to taste. The lower abv soju trend came during war times in Korea. To make sure there was enough soju to go around to all the soldiers, they would diluted it in half to double the quantity. The trend of low abv sojus held after the war and never really went back to the high abv style, at least not for the mass market.

There is no regulation or standard for soju abvs that you have to adhere to in Korea. You are free to release it at what expression you feel is best. Green bottle sojus have been declining in abv every year. Currently, most of the mass produced brands of soju have abv percentages that are in the teens.

We decided to release at two different abvs. The lower abv (Tokki White) at 23%, which also comes in a smaller 375ml bottle is more for the current trend of drinking with friends paired with food. The higher abv (Tokki Black) at 40%, comes in a 750ml bottle and is more of a nod to the old style sojus and more versatile. It is great for cocktails or just by itself.

Moving the Distillery to Korea

In recent news, Tokki Soju just moved their distillery from Brooklyn, New York, to Chungju, Korea. They also have plans to open a tasting room later this year, as well as their flagship bar in 2021. Tokki is launching a gin and a vodka brand this summer, making them the first to distill Western spirits in South Korea. A rum brand is also planned for 2021.

This will be a game-changer for cocktail bars in Korea, saving them on high import costs by giving them a local option.

The gin, Sonbi, will be distilled using citrus, flowers, and spices all native to Korea; only the juniper will be imported.

Camper: The decision to move the operation to Korea is a unique choice. What was the reason? I'm wondering if there were business reasons/incentives (such as the ability to be the first gin/vodka as a branding move, or government tax breaks or something), versus personal/relationship ones? I see it was mentioned "since all non-Korean spirits are currently imported at extremely high tax rates" that could be a factor if you're betting on sales in Korea.

There we many factors that went it to the move to Korea. First, you are correct, Korean importation taxes are very high on alcohol. We had an overwhelming fan base in Korea of people who wanted our products, but we were not able to come to market at a reasonable price exporting to Korea from New York. By not being able to offer a competitive price point exporting, we felt we would eliminate many demographics and send the wrong message about our mission.

Two, we thought if we were going to elevate the Korean spirits category we should start at the source and and produce in Korea. Three, the soju market is much larger here in Korea than the US and gives us more opportunities to grow.

Camper: Distilling – copper pot still in the US – pot with a column on top or just a pot still?

We have a hybrid still. We can run it as a pot and as a column. We do a two phase distillation in our process where we use both styles for our soju. First, is the pot stripping run and then cleaned up and finished with the column spirit run.

Camper: Did you move the still itself to Korea or get a new one?

We got a brand new still. We are using a much larger system now compared to our Brooklyn operation days. It is double the capacity of our old still.(1500 liters)

Camper: Assuming the soju will be made the same in the new distillery (it's a new distillery right?), did you get a new still for the vodka/gin – maybe not as I see the vodka base is rice plus GNS – are you planning to do self-distilled rice spirit plus GNS for the vodka? And for the gin is it just GNS or rice spirit in there too?

Yes, we have a new facility.

We did need a hybrid still to continue our same soju recipe, but it is great for a wide range of spirits. Our gin and vodka recipes are not finalized yet. We are in the trial and testing phases for both and looking forward to locking them down this year.

I can tell you that our vodka will be made with local sticky rice as well and our gin will most likely not contain rice, but will consist of botanicals unique to Korea that I have not seen in a gin before, like kul (귤) for example, which is a variety of Mandarin orange grown on the Korean island of Jeju.

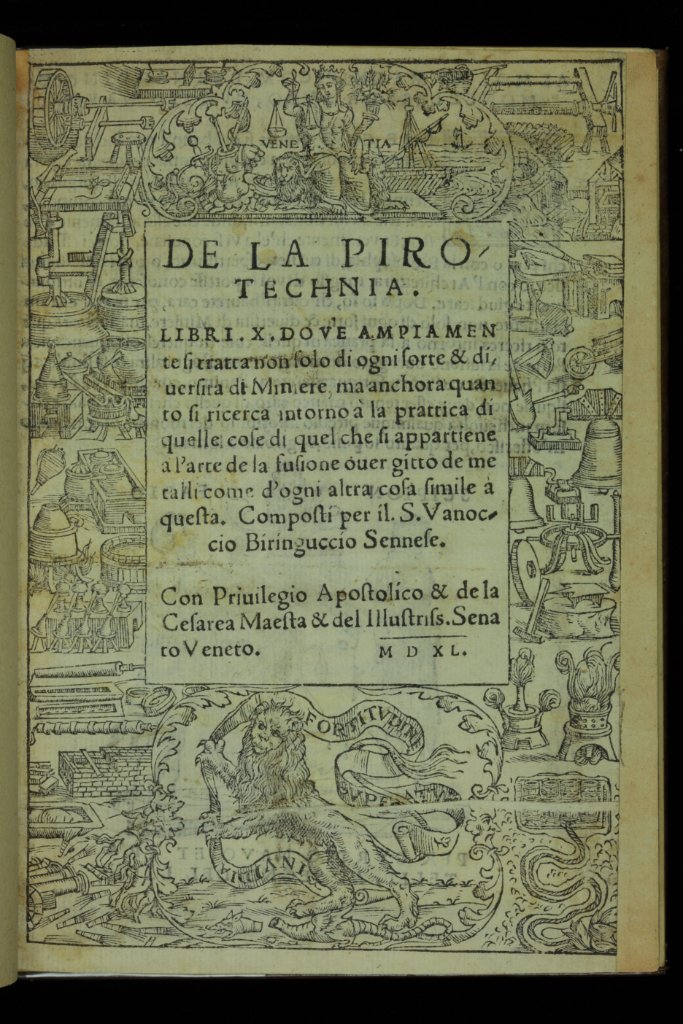

Aqua Vitae as a terminology comes from the "alchemico-medical" background – the medical alchemists separating a pure essence of the universal life force (supposedly) from wine. The name refers to the method (distillates were called waters) and (supposed) healthy life-giving impacts to the person who drinks it. It first referred to wine-based spirits but came to mean distillates of all sorts (and is the base of the words for aquavit, eau de vie, and whiskey) but then words like whiskey, brandy, etc came to dominate as spirits differentiated. A thing to note here is that this terminology and technology was from Southern Italy and spread up north in Europe toward the UK and Scandinavia, and eastward into Germany, Poland, and Russia. The technology of distillation of aqua vitae followed the path of knowledge with travelling monks.

Aqua Vitae as a terminology comes from the "alchemico-medical" background – the medical alchemists separating a pure essence of the universal life force (supposedly) from wine. The name refers to the method (distillates were called waters) and (supposed) healthy life-giving impacts to the person who drinks it. It first referred to wine-based spirits but came to mean distillates of all sorts (and is the base of the words for aquavit, eau de vie, and whiskey) but then words like whiskey, brandy, etc came to dominate as spirits differentiated. A thing to note here is that this terminology and technology was from Southern Italy and spread up north in Europe toward the UK and Scandinavia, and eastward into Germany, Poland, and Russia. The technology of distillation of aqua vitae followed the path of knowledge with travelling monks.