Hacienda La Caravedo is the oldest working distillery in the Americas and the place where they make Pisco Porton. It's located in Ica, Peru, about a four hour drive south of Lima. I visited in the spring of 2014.

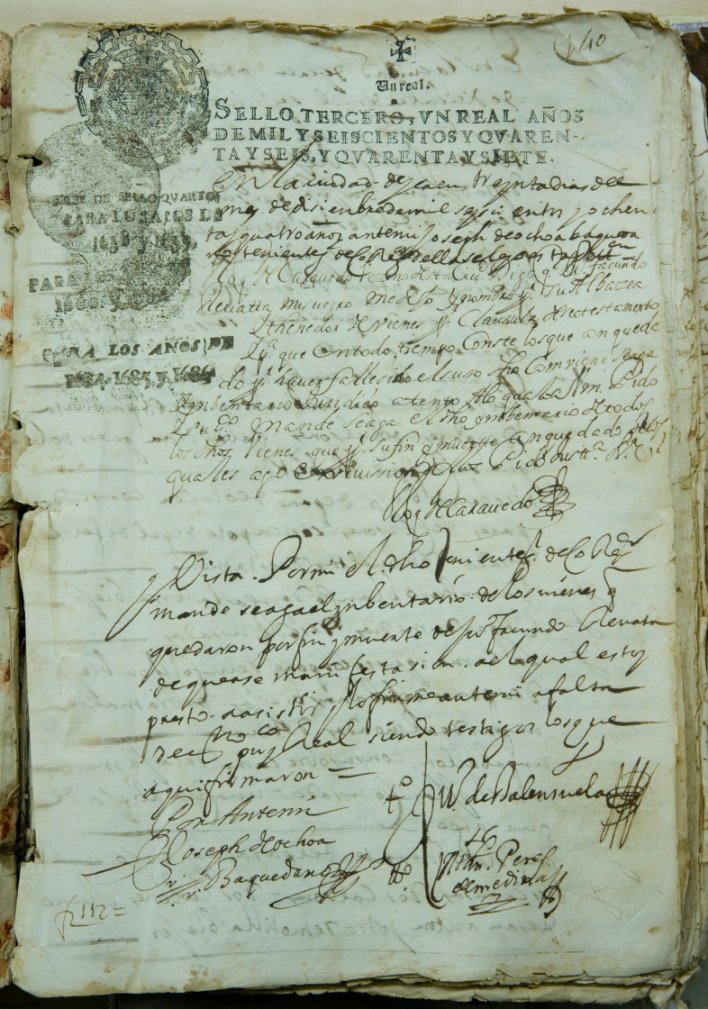

The distillery dates to 1684. Below is a picture of the document establishing the distillery.

The grounds hold the distillery, vineyards, and this huge house, which is newly-constructed.

You might recognize it from the bottle label. The house belongs to the owners of the brand. They were preparing for Easter when I visited so I didn't get to peep inside.

The vineyards are located between the house and the Andes mountains you can see in the background.

The Old Part of the Distillery

The distillery is an imaginative combination of the very old part dating to the 1600s and a very new part dating back a couple of years.

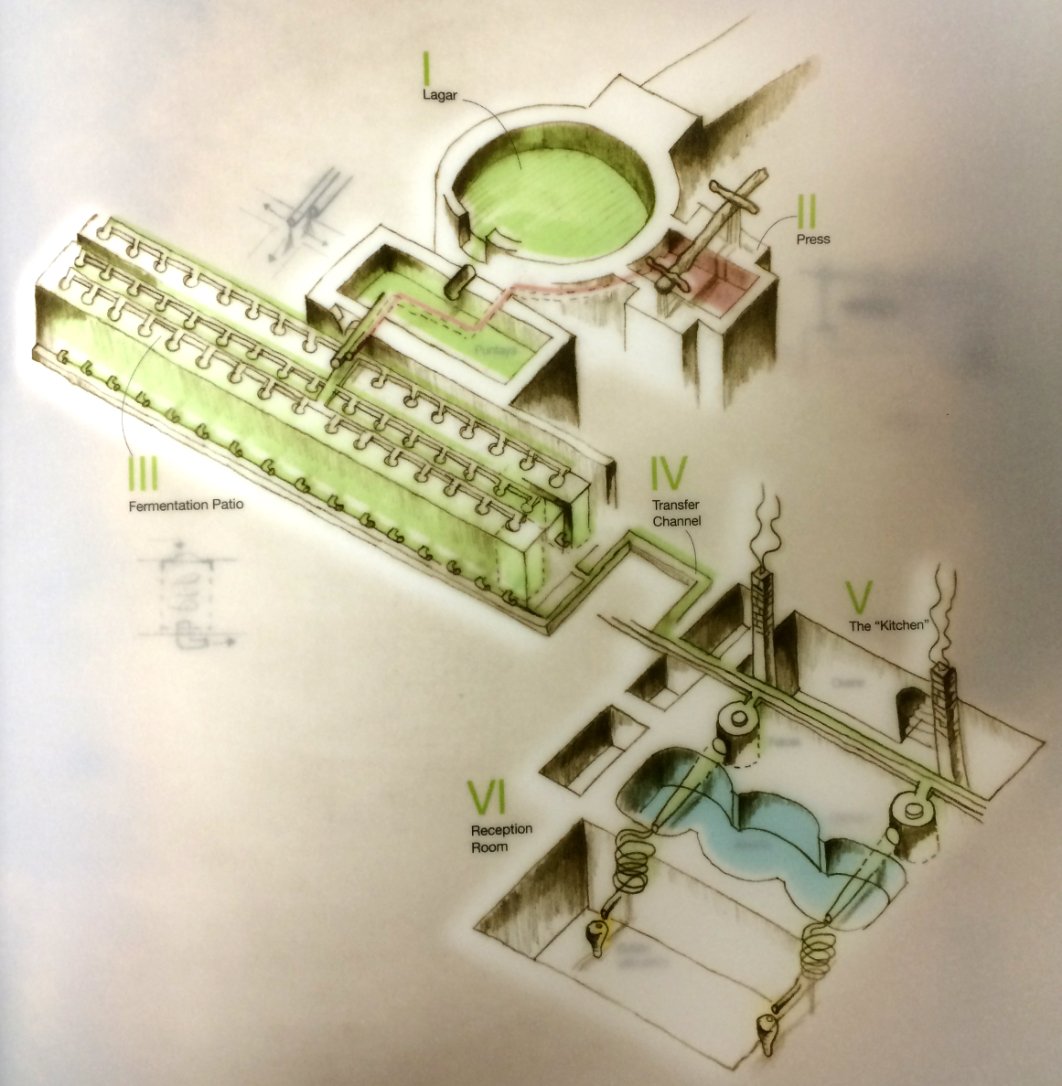

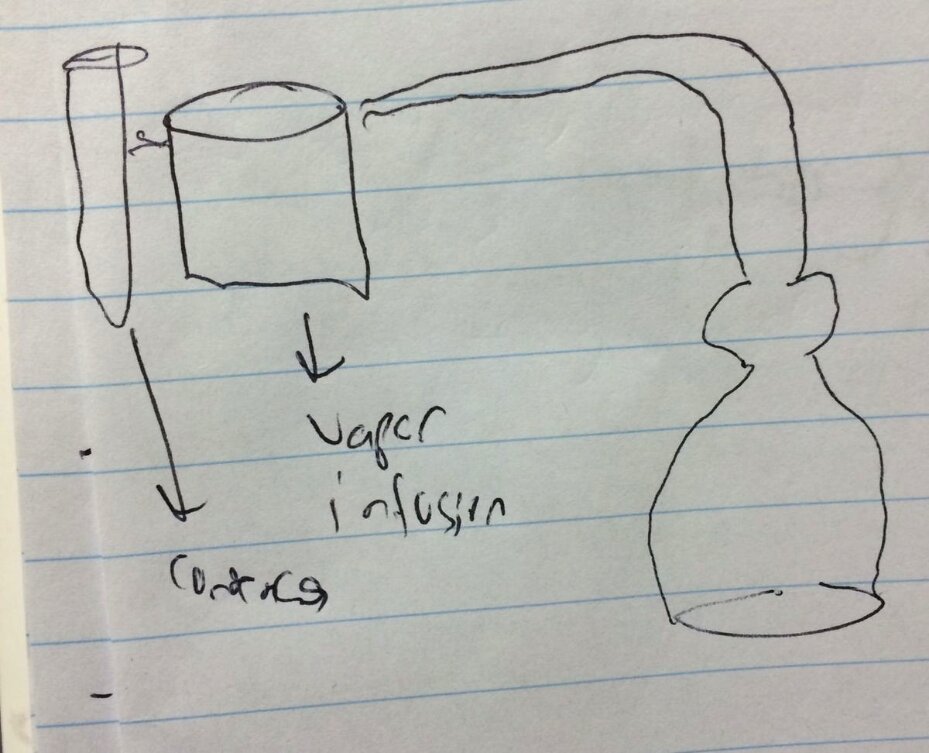

The original distillery was all run by gravity. A schematic from the Porton brand book is below. The process goes grapes to juice to resting to fermentation to distillation to resting again.

The grapes would come in from the winery and be carried up the stairs into a large circular pit with drains. That shallow (a few feet deep) pit is under the central round canopy in the picture below.

People would stomp on the grapes to release the juice, which would flow down to the next level for resting and fermentation.

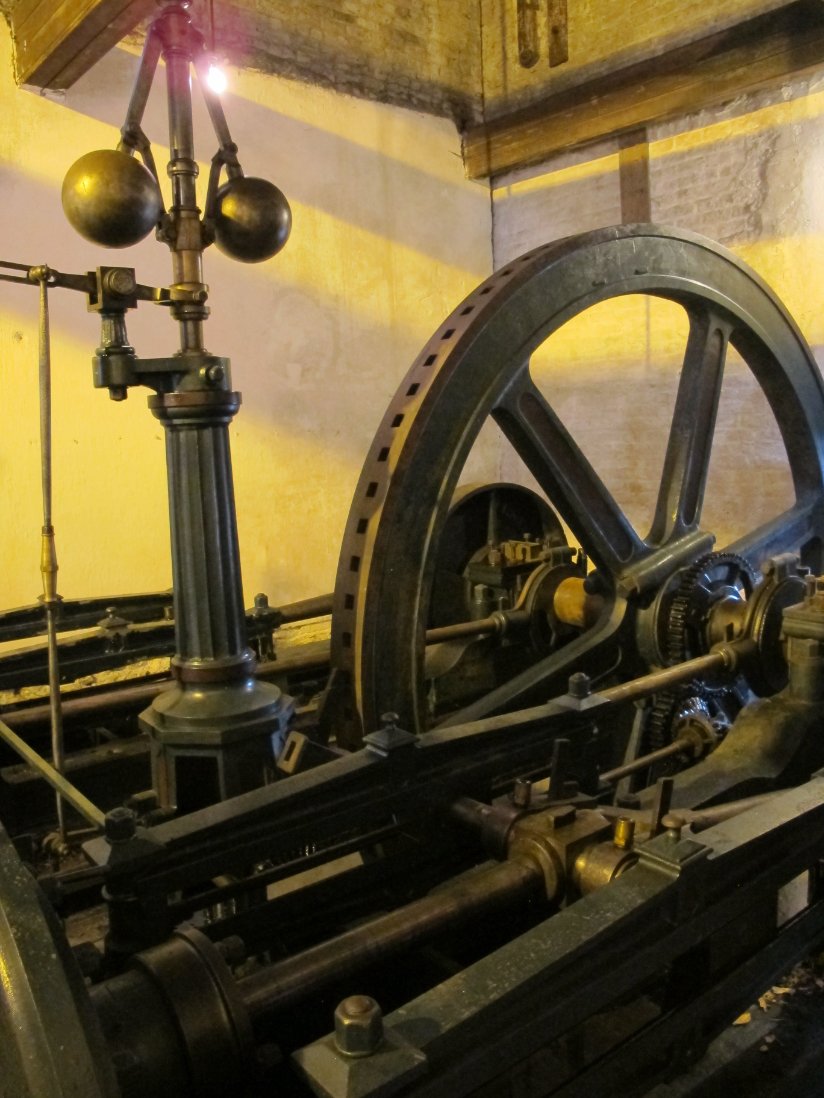

Then in the part where the square canopy is, grapes would be further crushed using the old grape screw press.

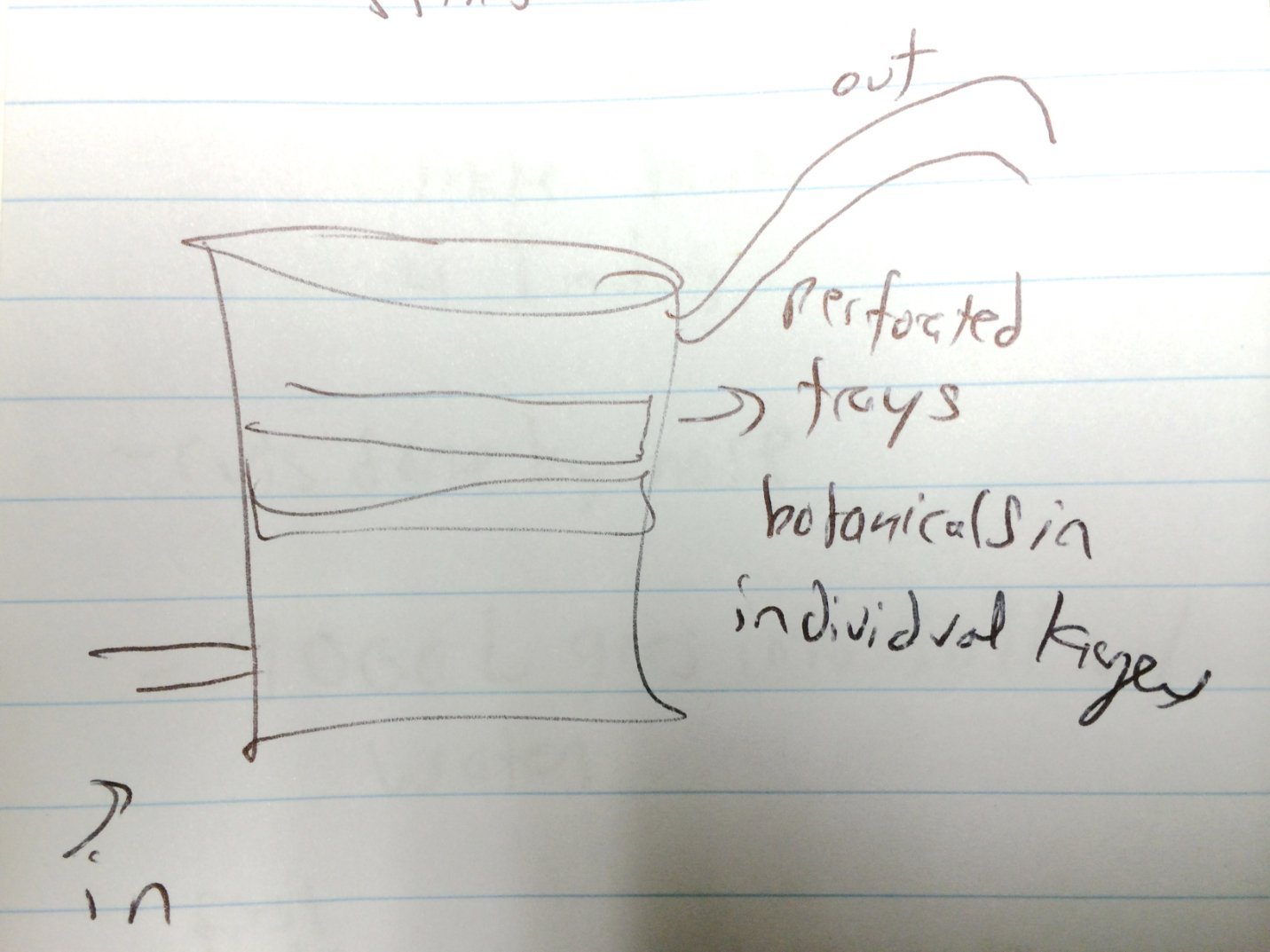

The grape juice ran down into a set of vats. They would allow the juice to sit together with the grape skins for a day. Pisco Porton still does this step, which distiller Johnny Schuler says is unusual.

Then the juice is transferred to another adjacent vat and fermented. The below picture shows the maceration and fermentation vats in the old distillery.

From the fermentation vat, the wine flows through a channel over to the old stills. Somehow I didn't get a picture of the channel, but it's a small open cement trough that runs across the lawn at ground level.

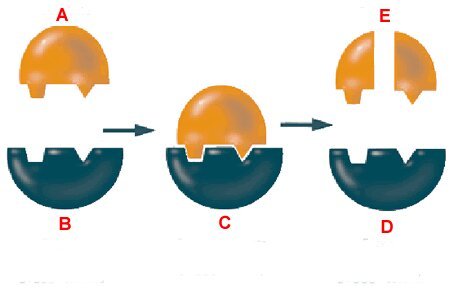

The old style stills at La Caravedo and other distilleries are called falcas. The top of the stills are at ground level (where the wine runs in), and the bottom is a level down. These old-style stills don't have a bubble cap like a typical pot still; they're like big boxes with a pipe running out the side. On top they're just a big copper cap.

These particular copper falcas, built into the original distillery's footprint, are probably 150-200 years old.

The stills are wood-fired from below.

After the spirit comes off the still (from a pipe on the side rather than through a swan's neck like in a pot still) it passes into the next chamber, the condenser.

The condenser is just a big pool with a copper coil running through it. The vapor from the still condenses back into liquid as it travels around the coil deeper into the pool.

Here is a view from the top of the pool, which is at the same level as the top of the falca.

Then in the next chamber down at the bottom of the pit the spirit is received. From a full distillation of 1500 liters, they produce 450 liters of pisco puro or 250 liters of pisco mosto verde (more on that in another post).

Peruvian pisco is distilled a single time, not twice like almost every other spirit in the world.

In the olden days, pisco would then have been rested in botijas, the ceramic/clay vases seen in every pisco distillery (often just for decoration now that we have cement and stainless stell).

The New Part of the Distillery

The new part of the distillery is a tall building of cement and glass, located across a small courtyard from the grape press structure. This is a view of the new distillery from the top of the grape press.

The fountain in the picture isn't just an aesthetic touch. The water used to cool the condensing steam from distillation heats up and needs to be cooled. At La Caravedo, they shoot that hot water up the fountain to cool in the air, a trick I haven't seen used at any other distillery.

Inside the distillery are rows of huge stainless steel tanks. These hold the fermenting wine.

On either side of the distillery are gargantuan cement tanks for holding the distilled pisco. Pisco always rests after distillation. In the old days, it rested in the ceramic botijas jugs. These cement tanks, which are on the outsides of the distillery to catch the sun, are meant to mimic the resting in botijas.

The still room is enclosed by glass. The stills are traditional copper pot stills, with round caps on top. Thus these produce a different spirit than the old-style falcas.

So, now we know the two ways that pisco is distilled and rested at La Caravedo in the modern and ancient distilleries on the property. In the next post we'll look at how these technologies are combined to give us the mosto verde blend of Pisco Porton. [Here is the post.]

Below are some more pictures from the grounds and my awesome day at the distillery.