This September I visited Cognac, France to judge a competition for Grey Goose vodka. While there, I learned about the production process. I'm sorry I don't have pictures of all this to share- you like reading, right?

Grey Goose is made in two parts: in Picardy, in the north of France, where the wheat is grown and distilled; and Cognac, France, where the wheat spirit and water are filtered and bottled.

The Wheat

Grey Goose is made from soft winter wheat grown in Picardy. In that region they grow tons of wheat for France (and you know how the French like baguettes). The temperature never goes below -5 degrees Celsius and in the summer not hotter than 25 or 35 degrees. Winter wheat is sewn in October and harvested in August, giving it 10 months to grow strong, as opposed to summer wheat that grows in 6 months and is more fragile.

The wheat is grown by many farms, then sold to and classified by a co-op. They use only that classified as "superior bread-making wheat" for Grey Goose. Soft wheat, as opposed to hard wheat, is better for distilling according to Maitre de Chai Francois Thibault. I takes about 1 kilo of wheat to make 1 bottle of vodka.

Milling and Fermentation

Interestingly, Grey Goose doesn't own their distillery, yet they have an exclusive contract with the distillery and they produce only Grey Goose there. The distillery is also located in Picardy, and it sounds like quite the huge operation. The entire distilling process is one continuous operation – wheat goes in and spirit comes out with the whole thing in motion.

The wheat, purchased from three different co-ops, enters the distillery, where it is cleaned and then milled. It is milled four times over the course of 24 hours. The husks, which won't ferment, are sold as cattle field. The flour goes through to fermentation.

To break the carbohydrates in the flour down into fermentable sugars, enzymes are added. They add one enzyme that cuts the starch into random sized pieces, then cool it, then add another enzyme that cuts those pieces into evenly sized fermentable sugars.

Why use enzymes? I asked Francois Thibault that question. He said that unlike barley, which can be prepared to transform into fermentable sugars by the malting process, wheat doesn't germinate (see geeky explanation by Ben in the comments). However, as with bourbon, malted barley could be added to the corn/wheat to help transform its starches into fermentable sugars. Thibault says though they could use malted barely, using enzymes is more stable, efficient, and cleaner; and no undesired microorganisms will be added during the process.

Now the wheat is ready for fermentation. They use a commercial (non-proprietary) yeast strain that is prepared elsewhere.

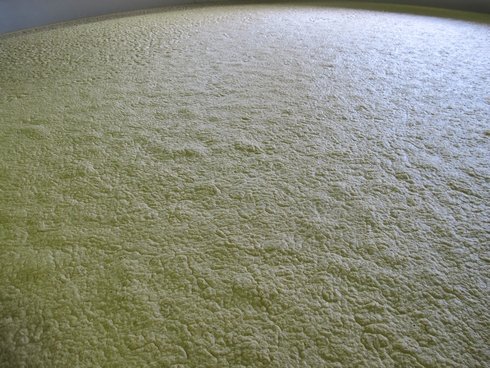

Fermentation takes place in a continuous manner – this is something I've not seen at other distilleries, though I think this technology is used elsewhere. Typically, the wheat/corn/whatever that is being fermented goes into a big vat, ferments completely, then the vat is emptied out. This is a batch process.

For Grey Goose, they use a continuous fermentation process over a series of six cascading tanks. Wheat and yeast goes in the first tank, then pours into each successive tank operating at a different phase in the fermentation process. At the end, the liquid is fully fermented in the form of a beer at 10% alcohol by volume. This takes about 30 hours. New wheat and yeast is constantly added to the first tank and beer is constantly pulled out of the last one.

Distilling

Then the beer is distilled into spirit. They use a five column distillation process. Despite the names given to each of thecolumn stills, they're more or less the same stills, just fine tuned with number of plates, pressure and temperature settings, etc., to do a certain job.

- The first column strips out the water and produces a spirit at 92% alcohol.

- The second column is tuned for "hydro-selection," meaning the spirit is watered back down before entering it, and it is redistilled to remove certain components.

- The third column is "rectification under pressure" and the fourth is "rectification under vacuum." Both of these strip out high and low oils.

- The last column is tuned for "demethanolisation."

The waste products of distillation are redistilled and sold off as industrial alcohol.

The entire process from when the wheat enters the distillery until it leaves takes four and a half to five days.

Filtration, Water, and Bottling

I didn't have the opportunity to visit the wheat fields and distillery in Picardy, but I did get to visit the bottling facility near Cognac.

The water used to bottle Grey Goose comes from a well 500 feet deep beneath the bottling plant. As the soil is full of limestone (just like in Kentucky), the resulting water is full of calcium.

The water is filtered to remove the minerals using double reverse osmosis. Thibault emphasized that the machine can't make great water out of bad water, so they have to start with good stuff like they have. Furthermore Thibault says they don't filter it to 100% pure H20 – they do it to their specifications and leave in the rest for character.

The water is mixed with vodka to bottling proof and then filtered again, this time through pads of cellulose and carbon.

I was curious as to why they don't just bottle the vodka up in Picardy. Thibault says they didn't really consider it – he was based in Cognac (he was a cognac and other spirit maker) when Sidney Frank asked him to develop Grey Goose, and he knew the water in the region was good. He says it was a practical decision to grow the wheat and distill in Picardy and transport it Cognac rather than ship the water of Cognac to Picardy or to try to grow wheat in the Cognac region.

Finally, the bottles are also produced in France. At the bottling facility they only bottle Grey Goose, no other products.

The Glycerin Question

Grey Goose has long been the victim of rumors that it has something added to it to make it smoother. Darcy O'Neil tested Grey Goose for glycerol and found none. But other additives are allowed by US law (sugar, and I think citric acid, for example). So I asked Thibault directly if anything was added to Grey Goose after distillation besides water. He said "Absolutely nothing," and I believe him.