I wrote my take on this subject for The AlcoholProfessor, where the story first appeared.

Why is Distilled Alcohol Called Spirits?

The word “spirit” has many definitions but most center around either the idea of the conscious self as opposed to the physical body; or an attitude, as in “the spirit of the movement” or “in good spirits.”

But given that this is Alcohol Professor we are concerned with the origin of the boozier definition today; that of “a strong distilled alcoholic liquor.”

That definition comes in at number 21 out of 25 definitions of the noun “spirit” via Dictionary.com. Most of the other definitions have to do with thoughts and feelings or with ghosts and demons (as in Spirit Halloween) and other intangibles. But unlike the rest of the terms, the “spirits” in the form of distilled alcohol are real physical liquids that you can hold in a bottle or pour into a glass.

The Origin of the Word Spirit

Looking instead at the etymology (the study of the origin of words and how their meanings have changed throughout history) of the word, we can see that ‘spirit’ is probably derived from the Latin spiritus meaning "breathing” or “breath” and also the “breath of life" as in the force that animates people; the force that gives them life.

How do we get from the word for breath and the concept of consciousness to the word for whiskey and vodka? The answer is not so straightforward, and we have to go through alchemy to see it.

Alchemy and Distillation

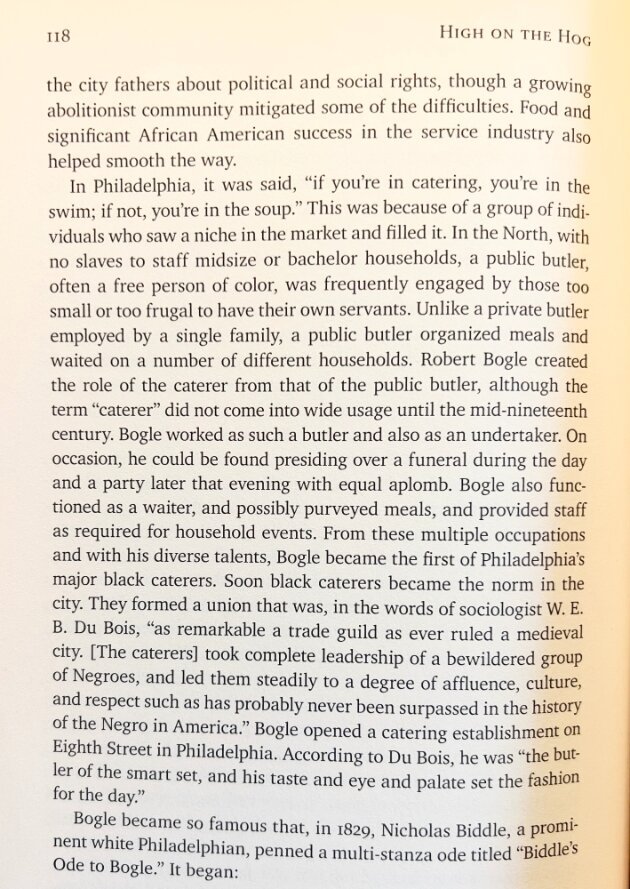

Doctors and Distillers by Camper English

To be clear, I am not a linguist or etymologist, but I have wrestled with this question as I wrote the book Doctors and Distillers. Or rather, I was wrestling with the concept that distillation of spirits came from the theory and practice of alchemy, and along the way I figured out why the word “spirit” would be used to describe the result.

Alchemy was not (only) a practice of magic or a profession of tricksters and scam artists. It was proto-science before science was formalized, and involved elements of minerology, chemistry, religion, astrology, astronomy, metallurgy, and more. It was an attempt to understand how the world works, and how to improve it.

And just how would they improve it? With distillation. Distillation was one of the most advanced tools of early chemistry, more sophisticated than things like filtration, boiling, corrosion, and dehydration. And it was a tool used to make both the philosopher’s stone and medicine.

The Western-style pot still dates to at least 300 ACE in Egypt, but we don’t have good evidence of distilled concentrated spirits in the West until after 1100. In that millennium in between, the alchemists used the still to separate materials; for example, metals that had been corroded by liquid acids.

Many different, complicated distillations were thought to be required to make the philosopher’s stone; a powder or other substance that would help speed up the supposedly natural evolution from lesser metals into perfect gold. The still was seen as a tool for extracting the intangible part of something to apply it to something else in order to change (or heal) it.

Medicinal Waters

At the same time, alchemists were using the same equipment to make distilled, preserved medicines and perfumes called “waters.” As we know from distilling red wine or yellow grains, everything that comes out of a still is clear, or the color of water. So things like rosewater and orange flower water were distillates from those plants.

Distillation leaves the solid parts behind in the still and imbues the resulting colorless liquid with the flavor and scent – and healing properties – of the original matter. Thus, the alchemists thought of this as creating a “water” with the “active energy” of the original material. And that energy could be applied to other things.

Much like creating the philosopher’s stone meant to ‘heal’ a lesser metal into gold, medicinal waters could heal humans into healthier form. This concept of active, reanimating energy from plants contained within distilled liquid medicine (the breath of life!) seems the most likely origin of the term “spirit.”

The Water of Life

We see real written proof of concentrated alcohol produced from the still before the year 1200 in Southern Italy. The distilled wine, used as medicine, was called the “water of wine” at first, then “burning water” as it could be set on fire, and eventually aqua vitae or “the water of life” when distillation technology improved, and the distillate’s superior healing and invigorating powers were explored further. (It can’t be understated how big of an improvement distilled spirits were to medicine; the alchemists thought they could prolong human life significantly with it.) The terminology became more formalized in writings of the 1200s and 1300s.

These terms were written in Latin, the language of science in the Middle Ages, before being translated into languages like French (where knowledge of distillation travelled from Italy), German, and other languages. “Aqua vitae” becomes “eau de vie” in French, “aquavit” in Scandinavia, and even “whiskey” in English via the Gaelic “uisge beatha.”

At the same time, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word “spirit” comes from mid-thirteenth century French, based on the Latin word spiritus. This seems to fit our timeline perfectly – the water of life gives the breath of life to people who ingest it. By the late 1300s the word “spirit” comes to mean “distillate” directly.

Now, the Latin word spiritus also corresponds to directly “breath,” referring to wind and respiration, so could the origin of the word simply refer to the moist alcoholic vapor produced in the process of distilling?

That’s possible, but given the important symbolic medicinal properties of distilled alcohol, my vote is still for the definition of “spirit” as the breath of life, the active energy, or the animating principle of the universe distilled into liquid form.