My first story for PopularScience.com is a report on the bartenders from BarBot, held this past weekend in San Franicso.

Go here to read the story!

It's mostly a slideshow with videos as well.

My first story for PopularScience.com is a report on the bartenders from BarBot, held this past weekend in San Franicso.

Go here to read the story!

It's mostly a slideshow with videos as well.

This February I was lucky to be invited to visit the Nordic Food Lab, which is located on a boat floating in a harbor off Copenhagen. It was formerly the research lab of the world's top-rated restaurant NOMA, and I believe they still have a close relationship and work together on projects.

The lab is pretty small: A few work tables, refrigerators and cabinets on both sides of the room, and tons of samples in bottles, barrels, bags, and jars everywhere. It reminded me a lot of my apartment, except that the swaying back-and-forth was coming from the water beneath the boat, not the booze in my belly.

There I met Ben Reade, a scientist at the lab. He described some of the cool stuff he was doing, such as:

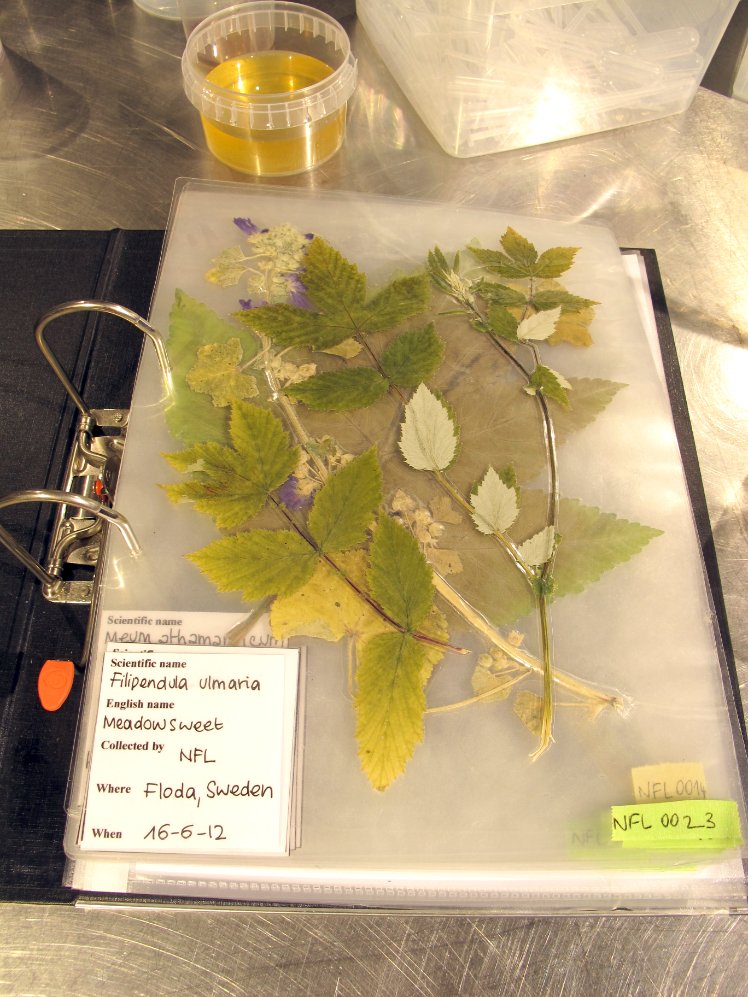

Going into the Swedish forest and collecting all sorts of possibly-edible plants

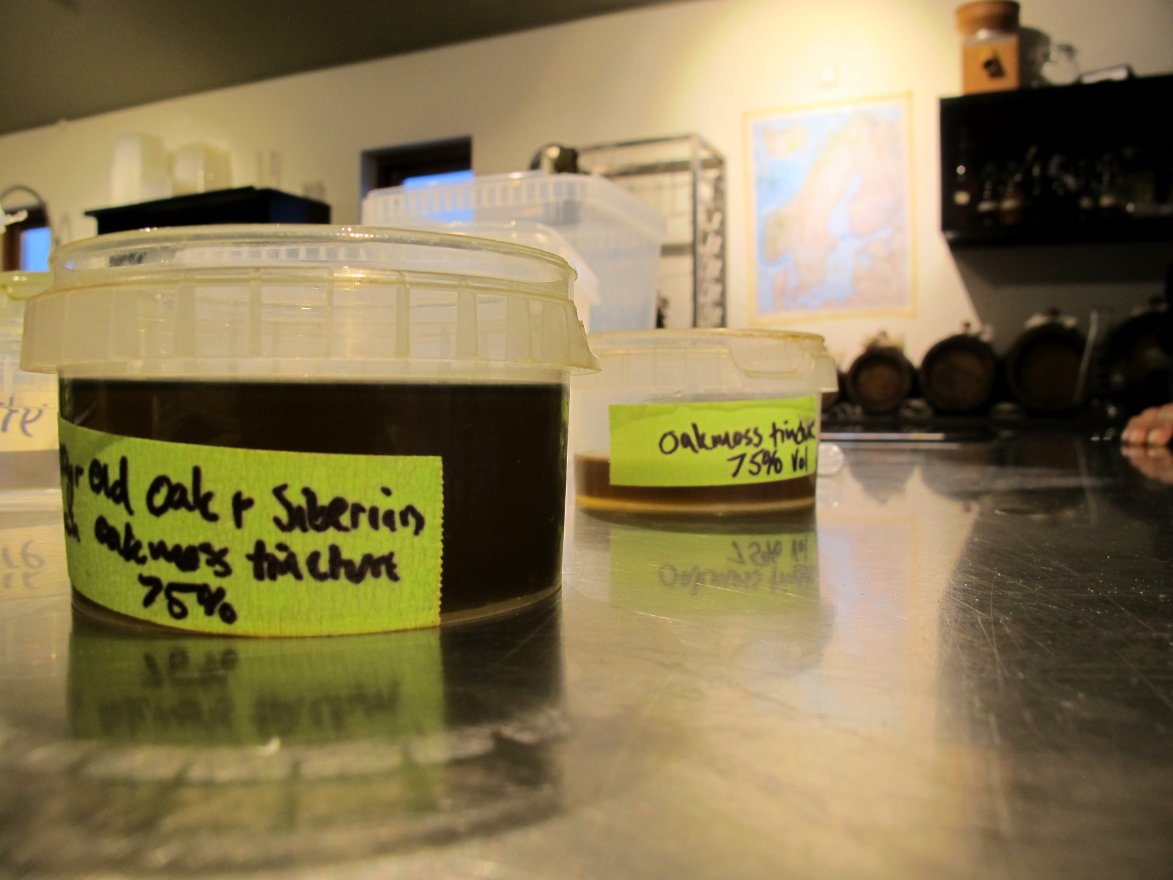

and doing all sorts of experiments with them, like making tinctures out of them.

He also brewed beer and added three different levels of (incredibly bitter) oak moss to it so see how it tasted.

I'm not sure what they're doing with this drying (boar?) leg, but they're attempting traditional curing/drying techniques. The one on the right is coated with some sort of wax.

He's also working a lot with fermentation. He made a vinegar from fermented elderflower, which led to us having a long discussion on shrubs and drinking vinegars.

He was also experimenting with kombucha – we tasted a ton of it with different levels of pear juice to seek the optimum amount.

He was also aging vinegar in a mini-solera. How much do I want a set of these barrels?

At the end of the visit we got to taste some non-sweet sugar with added lactasol (not sure if I am spelling that correctly). It's a chemical that inhibits the perception of sweetness. So the powder we tried is mostly sugar but it tastes like nothing.

Therapeutically it can be given to anorexic people mixed with high-sugar foods as apparently they don't want to eat anything sweet, but of course my thoughts went to cocktail applications: a drop of it in a too-sugary cocktail could dry it right up! (Unfortunately he said it's usually only available in massive-sized quantities.)

Overall the visit was very cool and very inspiring, making me wish I had more space for more experiments at home.

You can read about the work being done at the Nordic Food Lab on their research blog.

For CLASS Magazine online at DiffordsGuide.com, I wrote an article about filtration in spirits. This was based on the research I did for my talk on the subject at the Manhattan Cocktail Classic earlier this year.

Don't Forget the Filtration Factor

By Camper EnglishNearly every spirit undergoes some sort of filtration, yet we rarely acknowledge it as part of production. But filtration makes vodka what it is today, practically defines Tennessee whiskey, is the standard in making white rum, and is changing the look of tequila. Filtration is important.

Generally speaking, filtration refers to the mechanical process of passing a liquid or gas through a medium that keeps out solids of a certain size. But in spirits, we include carbon filtration (sometimes called carbon treatment) as filtration too. Carbon filtration works differently: by absorption, the adhesion of particles to a surface, like flypaper.

I researched filtration in spirits for a talk at this year's Manhattan Cocktail Classic. While I can't claim category-wide or hands-on expertise in this matter, I spoke with several industry sources who know their stuff. Consider this an introduction to the subject.

The article covers filtration in vodka, rum, tequila, whisk(e)y, and cognac. I hope you'll find it interesting. Get the full story here.

Update: The story came off the site, so here it is in its entirety:

Filtration in Spirits

Camper English

Nearly every spirit undergoes some sort of filtration, yet we rarely acknowledge it as part of production. But filtration makes vodka what it is today, practically defines Tennessee whiskey, is the standard in making white rum, and is changing the look of tequila. Filtration is important.

Generally speaking, filtration refers to the mechanical process of passing a liquid or gas through a medium that keeps out solids of a certain size. (Think of a screen door.) But in spirits, we include carbon filtration (sometimes called carbon treatment) as filtration too. Carbon filtration works differently: By adsorption, the adhesion of particles to a surface. (Think of flypaper.)

I researched filtration in spirits for a talk at the Manhattan Cocktail Classic in May 2012. While I can’t claim category-wide or hands-on expertise in this matter, I spoke with several industry sources who know their stuff. Consider this an introduction to the subject.

Vodka, Charcoal, Tequila, and Rum

Early vodka was surely very different from the perfectly clear, nearly-neutral spirit we know today. True, distillation was cruder, performed in pot stills rather than in today’s hyper-efficient columns, but filtration helped rid vodka of lots of nastiness. Much early vodka filtration seems to resemble “fining” in wine and beer – a fining agent speeds up precipitation of impurities in the liquid. Fining agents have included egg whites, milk, gelatin, fish bladders, something called “blood powder.” Vodka has also been filtered through sand and other soils (this process is still used in water treatment), felt, and other materials.

But activated carbon (charcoal) seems to have the largest impact on vodka and other spirits, or at least it is the most commonly used filtration method. In vintage vodka, charcoal derived from trees was used to clean up the liquid, but today charcoal for filtration may come from wood, nut shells (coconut especially), and even bones. (Fun fact: some white table sugar is clarified using bone charcoal, rendering it non-vegetarian.)

Vodkas today advertise a range of other material to complement the carbon. These include birch charcoal, quartz sand, and algae (Ladoga), Herkimer Diamonds (Crystal Head), freeze filtration, Z-carbon filter, and silver (Stoli Elit), Platinum (Platinka), Gold (Lithuanian), Lava Rock (Hawaiian, Reyka), and marble (Akvinta). Though many of these methods sound like pure marketing, in fact some of these precious materials like platinum and silver do improve filtration efficiency. (For very detailed information on some vodka filtration technologies, this site https://www.vodka-tf.com/ is quite a read.)

Charcoal filtering is also commonly used in tequila. According to one tequila producer, this is because the law for tequila production (the NOM) specifies amounts of impurities like esters and furfural that may be present in tequila, and these numbers are difficult to consistency hit with distillation alone. Thus, charcoal filtration cleans up the impurities in tequila a little bit – but also removes some flavor with it.

Charcoal filtration can remove color as well as flavor and impurities. Many ‘white’ rums are aged a year or more in ex-bourbon barrels, and then filtered for clarity. Charcoal filtration (and other new-at-the-time technologies such as aging and column distillation) helped make Bacardi the popular and later global brand of rum that it is today. This lighter, clear style of rum born, in Cuba, is often called the ‘international style’ that won out in popularity over regional production methods.

All charcoal isn’t created the same, however. Should you take a dark rum and run it through a water filter repeatedly, you may not lose any color. (I tried.) Some parameters that distillers investigate in choosing the right carbon filtration material include the base material (bone, nut charcoal, wood, etc), the “iodine number” and the “molasses number,” the latter a measurement of decolorization. Activated carbon meant for cleaning up water may not be of any use in stripping color from liquids.

Decolorization has allowed for a new trend in tequila: aged tequila filtered to clarity. Probably the first tequila to do so was Maestro Dobel, a blend of reposado, anejo, and extra-anejo tequila filtered to near-clarity. In recent months, new brands have followed suit, including Casa Dragones (blanco and anejo mixed together and clarified), Milagro Unico (blanco with ‘aged reserves’), and Don Julio 70th Anniversary Anejo Claro (clarified anejo). In the opposite direction, the first tequila that I’ve seen labeled as ‘unfiltered,’ a special cask-strength bottling of Ocho, has also just hit the market.

Whisky and Cognac

In both scotch and in bourbon, there is an increasing trend toward unfiltered whiskey, while chill filtration is still very much the norm. Chill filtration prevents cloudiness in spirits (particularly at low temperatures) and precipitation of particulates in the bottle. It is purely an aesthetic choice, not meant to affect the flavor of the spirit. However, many experts argue that it does alter (flatten) the flavor to some extent. (For a very nerdy analysis of chill filtration, we refer you to this information from Bruichladdich https://www.bruichladdich.com/library/bruichladdichs-guide-to-chill-filtration.)

As far as I have been able to learn, in chill filtration activated carbon is not used. The spirit is chilled to a certain degree, and then a cellulose or other paper filter is used to remove the esters and fatty acids that are less soluble at low temperatures. Whiskies bottled at higher proofs tend not to cloud, so many cask-strength whiskies and many (if not most) whiskies bottled at 46 percent alcohol or higher are non-chill filtered. Outside the bottle, however, when ice or water is added and they dilute, they may get cloudy.

Tennessee whiskey has its own style of filtration. After the spirit is distilled but before it goes into the barrel for aging, the whiskey is dripped through or soaked in tubs with about ten feet of charcoal made from sugar maple trees. Contrary to popular opinion, this is in no way required by law, but both Jack Daniel’s and George Dickel employ this technique. Gentlemen Jack is unusual in that it undergoes charcoal filtration a second time before bottling.

One cognac distiller revealed that filtration in cognac is also standard: cognac is run through paper filters of a specific (depending on the product) pore size to filter out undesired molecules. While most cognac is not chill-filtered, one producer said that when bottles are destined for cold-weather countries (cognac is popular in Scandinavia), it is often chill-filtered to prevent cloudiness in the bottle. It might be interesting to taste chill and non-chill filtered versions of the same cognac. The opportunity is rarely, if ever, afforded in scotch.

So, some form of filtration is used in about every type of spirit, whether that’s to change the color, clean up undesired impurities or clean out off flavors, to prevent cloudiness, or just to keep out chunks of stuff from floating in your bottle. As with the water used in fermentation, the type of still, and the location/condition of aging barrels, filtration is an important part of the process of making spirits and shouldn’t be so often overlooked.

While at Tales of the Cocktail Vancouver, I attended the seminar on dilution by Audrey Saunders and Harold McGee. Saunders is the owner of the Pegu Club in New York and McGee is the author of the seminal work On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen.

Part of the discussion was about why we get more aroma in weaker drinks rather than stronger ones. People add water to whisky and other spirits when nosing them to release aromatics, yet this is counter-intuitive: shouldn't the whisky on its own have a more intense flavor that a whisky with just water in it?

The explanation is:

Saunders has been making a series of "inverted cocktails" in which she uses 2 parts of a weak ingredient like a fortified wine to 1 parts of the strong ingredient like whisky. These inverted cocktails are more aromatic than the stronger (1:2) versions of the same drink.

Other fun facts learned in the seminar:

I was lucky enough to get a sample of the Perlini cocktail carbonating system, but before I even got around to using it I was fascinated by carbonation information the instruction manual.

Note: Yes, I read the instruction manuals. Pretty much always.

The Perlini is basically a cocktail shaker than you fill with carbon dioxide (CO2), then shake and pour. The manual comes with tips both for using the shaker, and also about carbonation in general.

So here are some things I learned:

– The amount of CO2 that will go into solution is controlled by pressure and temperature. The higher the pressure, the more CO2 fits. Obviously when you release the pressure (such as opening a bottle of a carbonated beverage) the pressure equalizes and the carbon dioxide comes out of solution.

– The colder the temperature of the liquid, the more CO2 can go into solution. Thus in the case of the Perlini, you add ice to the cocktail shaker. You can also chill the liquids in advance and not use ice (though the shaker is optimized for ice).

– To keep the carbon dioxide in solution, we want to minimize the amount of bubbles that form and carry CO2 out of solution. Bubbles form when microscopic pockets of gas are found in imperfections in a piece of glassware (note that in a champagne flute most bubbles form a stream from certain points at the bottom and sides of the glass) or in debris (solids) in the drink. These imperfections and solids are called nucleation points. The CO2 diffuses into these tiny pockets and blows them into bubbles, which are buoyant and float to the top and release the CO2 into the air.

– Your tongue has lots of nucleation sites for bubbles to form, and that's where we like them as it tingles. So we're trying to keep the CO2 dissolved into liquid until it hits our tongue.

– When using the Perlini (or say if you wanted to create a bottled soda) you want top keep nucleation sites out of the container. Thus you want to avoid having solids (like bits of citrus from fresh juices- strain them instead).

– Also, the surface area of ice has lots of nucleation points. So you want to decrease the total surface area of ice, by using larger cubes rather than chipped ice.

– The Perlini is meant to be shaken like a cocktail shaker, but when you do this bubbles form in the shaker. Thus they recommend waiting until the bubbles settle down before cracking open the shaker- otherwise it can foam over. Viscious liquids (liqueurs, milk) will hold bubbles for longer, so you need to wait longer for the shaker to settle before depressurizing.

– You're also not supposed to strain the liquid coming out of the strainer when you pour the cocktail. There is a built-in strainer to keep the ice out of the drink, but double-straining will add more nucleation points and fizz while you're pouring it through the strainer. Instead, strain any drink before putting it in the shaker. This cuts down on nucleation points from the pulp, etc. before you shake it. Also, pouring it on new ice will increase nucleation points as well.

– Carbonated beverages taste more tart than non-carbonated beverages. This is because CO2 dissolved into water produces carbonic acid, which itself is flavorless but somehow adds the perception of tartness.

– To adjust for the above, you should adjust citrus cocktail recipes towards the sweeter side so they come into balance when carbonated.

– Egg white (and other high-protein) drinks are going to be problematic as they are very foamy.

– "The acidity from the carbonic acid can interact with the tannins of wood-aged spirits in a way that emphasizes acerbic notes in their flavor profi les, requiring extra care in optimizing recipes." Weird.

I am excited to crack this thing open and give it a try. I am especially curious to experiment on how carbonation affects the perception of tartness and tannins!

I have a short piece in Tasting Panel Magazine about the instant infusion method – using a whipped cream charger filled with nitrous oxide to infuse flavors in spirits – and Purity Vodka's promotion of the technique.

The story is at this link, which opens a digital magazine reader.

By the way, the original Dave Arnold post annoucing this method is here at CookingIssues.com.

Here is my latest story in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Sweetening drinks can be a science

Camper English, Special to The Chronicle

Friday, January 8, 2010

Gin that bruises, 500-year-old secret recipes and miracle hangover cures. The world of cocktails is rife with myths and misinformation. As we slowly move out of the Dark Ages and into the cocktail Enlightenment, bartenders are starting to use scientific methodology to disprove hearsay and improve drinks.

Some of that science will be explained Jan. 20 at the Exploratorium. A one-night event (sold out, though the Web site promises to share details for home experiments) will include exhibits on the science behind layering a pousse-café, why absinthe turns white when water is added and how cocktails are affected by the shape of ice.

Having experimented with ice in recent years, many bartenders have moved on to studying sugar. Simple syrup is used to balance acid in many cocktails, so several curious bar types have purchased refractometers and pH meters to measure exact levels of each.

Read the whole story on the science of sweetening drinks here.