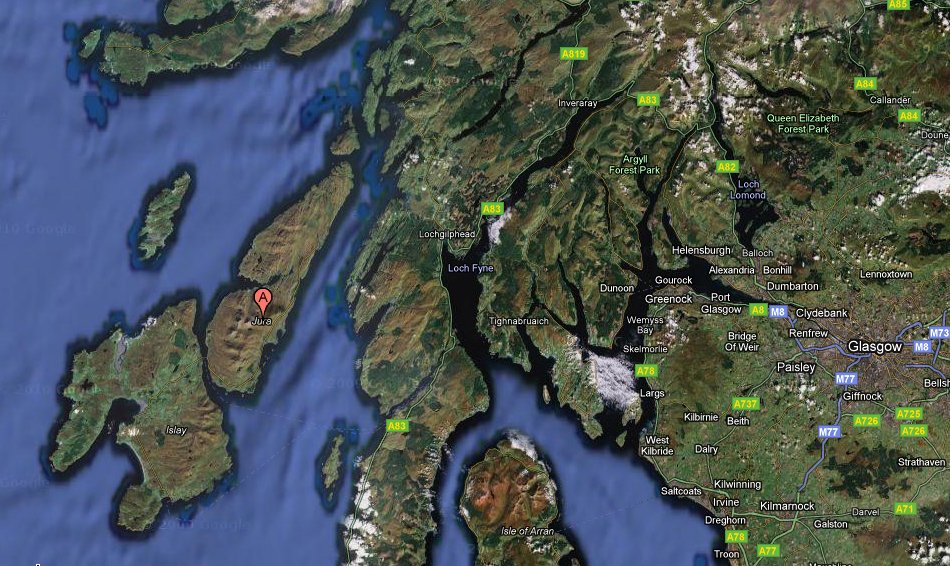

In June I took a short trip to Islay, Scotland to see how Laphroaig single-malt scotch whisky is made. Islay is an island off the coast of Scotland known for its smoky, peaty whiskies.

What Laphroaig does differently from other scotch producers, as you'll read, is:

- Floor maltings

- Separation of malt flavoring (with peat smoke) and malt drying

- An uneven number of pot stills

- Quarter Casks

Floor Malting

Laphroaig is one of six scotch makers that floor malts some of its own barley. Floor malting is the historic technique of preparing barley for fermentation. Most of the 100 distilleries in Scotland purchase malted barley from commercial malting plants, and most (all?) of the distilleries that do floor malting also purchase additional malt from commercial malters.

The other distilleries that malt their own barley are Bowmore and Kilchoman on Islay, Highland Park on Orkney, Springbank in Campbelltown, and The Balvenie in Speyside on the mainland. (Other brands including BenRiach have announced considering it.)

In floor malting here at Laphroaig, barley is soaked three times at room temperature (simulating spring rains), then spread out over a floor where it will begin to germinate. During four days in the summer (seven in winter), the malt is turned over with rakes to reduce heat build-up and release Carbon Dioxide that builds up in the piles. Then it is dried to halt germination.

Traditionally, the wet barley was dried over the local fuel source, be that peat (thick blocks of muddy decaying vegetation from bogs, on its way to becoming coal), or actual coal in the case of Highland distillers that had access to coal from the railroads. Now that other sources of energy can be used to blow hot air through the barley to dry it, smoke isn't necessary in the flavor of scotch. From commercial maltings, distillers can specify the level of smokiness they want their malt made.

Harvesting Peat

But for distillers with floor maltings who want smoky scotch, that means harvesting the local peat to burn for fuel. We donned Wellington work boots and headed out into the bog.

The peat for Laphroaig is all harvested by hand. The procedure is to first cut off a top layer of grassy soil that hasn't decayed enough yet and place it on the next row over so it will keep decaying. Then peat is cut in long brick-shaped pieces by pushing down into the muddy peat with a special peat cutting tool, then placing it on the surface grass to dry outdoors.

Click through the images below to see me harvesting peat.

The seaweed and other Islay plant-rich peat harvested here imparts more "peaty" (earthy and medicinal) flavor characteristics to the barley than peat harvested from the mainland (which may be comprised of other vegetation), which imparts more wood smoke flavors.

After the peat dries outdoors (but before it is too dry, as moist peat gives off lots of the desired smoke), they bring it back to the distillery where it is time to use it to dry the wet barley on the floor of the malting house.

I Peated in Your Scotch

Wet peat is moved into the drying room, which sits a floor above a big boxy fireplace like on a steamship. Down below, peat is shoveled into the fire and the smoke rises to the room above to engulf the wet barley with smoke aroma. I took a turn throwing some peat onto the fire so you could be drinking my handywork in ten or so years.

Laphroaig is unique in that first they flavor the barley with smoke for 17 hours, and then after that they pump hotter dry air through it for an additional 19 hours to fully dry the barley. Other floor malting distilleries do the flavoring and drying steps together.

This longer, slower flavoring and drying method changes the flavor profile of the barley, and the finished product – it doesn't just make it smokier. According to Master Distiller John Campbell, when we talk about the phenol profile of a whisky we're talking about 5-7 flavor components. The process of flavoring the barley at Laphroaig particularly brings out 4-ethyl glycol guaiacol and creosole components, present in other whiskies but not to the same extent as in Laphroaig.

The malted barley made at the distillery is mixed with malted barley made just down the road at the Port Ellen maltings, along with malted barley from the mainland as well. Now it's time to ferment and distill.

Fermentation and Distillation

The water source for Laphroaig is a large reservoir a ways from the distillery, uphill.

The dried, malted barley is then ground up and put through the "mashing" process. Hot water is added to the barley and this inspires the enzymes released through the malting process to break the starches into fermentable sugars.

Next they collect the sugary water and discard the solids, adding yeast to allow the sugar water to ferment over 55 hours into a beer. Then it's ready to be distilled.

At most scotch whisky distilleries, the stills come in pairs. A larger still (wash still) performs the first distillation, and a smaller one (spirit still) paired with it takes on the second distillation.

Here at Laphroaig, things are weird. There are 3 wash stills and 4 spirit stills. The 3 wash stills are all the same size, but there are 3 small spirit stills and 1 big one with twice the capacity of the small ones.

One batch of fermented beer fills up 5 wash stills, so what they do is run 3 wash stills to go into 3 small spirit stills, then 2 more wash still runs to go into the one big spirit still.

Campbell says that the large and small spirit stills produce different tasting whiskies, but it's because they run the larger spirit still distillation too fast. (They've been doing it for 40 years that way though, so he's not about to change it.) The big still produces heavier, slightly oilier spirit as opposed to the lighter, sweeter, fruitier spirit that comes off the smaller spirit stills. Regardless, they blend all these together before putting it in barrels.

Barrel Aging

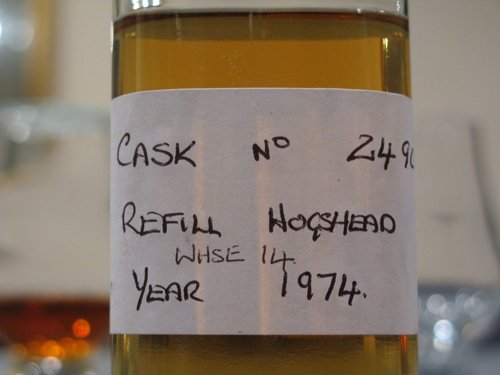

The spirit is 136 proof after distillation (68% ABV), but they put it into the barrel at 127 proof, which is common in the industry.

Nearly all Laphroaig is aged in ex-Maker's Mark barrels. On Islay, they have 8 warehouses holding 50,000 casks. As is now the norm in Islay scotches, they also age some of their stock on the mainland. However, Campbell says that he believes the majority of the whisky used in the single-malt Laphroaig (as opposed to stuff sold to other brands for blending) is aged on the island. He says aging on the island imparts earthier, saltier notes to the whisky.

The warehouse we visited is four floors tall and is the largest warehouse they use. Campbell says they get great flavor out of the whisky aged in this warehouse, but less color extraction from the wood as in their other warehouses. (The other warehouses are covered with metal and get hotter than the oceanside warehouses with their thick walls.) But putting together the barrels for the final products is the job of the blender.

The Range

10 Year – This is 70% of Laphroaig's single-malt sales. Minimum of 10 years aging in ex-bourbon casks.

Quarter Cask – After aging 5-11 years in ex-bourbon barrels, a blend is made and then it is further aged in "quarter casks" for 7 months.

Quarter casks are a quarter the size of a sherry butt, though they are made out of ex-bourbon barrels. They hold 30 gallons as opposed to 55 for bourbon barrels. These smaller casks impart more wood influence into the spirit in a smaller amount of time.

Triple Wood – This starts with the Quarter Cask liquid, then it is aged for an additional 2 years in ex-oloroso sherry casks.

I made the point that since quarter casks are actually made out of ex-bourbon casks, this is technically only two woods, not three. Lies! Maybe they should have called it triple barrel instead…

PX – This is the same product as the Triple Wood (that is actually double wood), except for those additional 2 years it is aged in ex-Pedro Ximenez (PX) sherry barrels instead of oloroso. This bottling is only available at duty-free.

18 Year Old – A minimum of 18 years in ex-bourbon barrels.

Cask Strength – This is the 10 Year Old at cask strength. Previously this was a blended product so that each bottle tasted the same (called Original Cask Strength), but now they release this in batches, so it should be a little different with every batch.

The Water Project on Alcademics is research into water in spirits and in cocktails, from the streams that feed distilleries to the soda water that dilutes your highball. For all posts in the project, visit the project index page.

The Water Project on Alcademics is research into water in spirits and in cocktails, from the streams that feed distilleries to the soda water that dilutes your highball. For all posts in the project, visit the project index page.