In a series of posts I've been nerding out about cognac production, after sending a list of 100 questions to Hine cognac's cellar master Eric Forget, and combining that information with what I can pick up in books and elsewhere.

In this post, I'll talk about diluting and additives used in cognac. There is a lot that happens in between taking cognac out of a barrel and it being sealed up in a bottle.

The posts in this series are:

1. Cognac from grapes to wine.

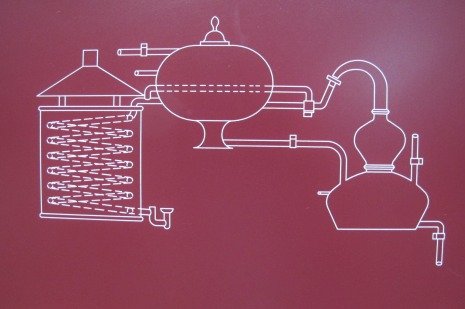

2. Cognac distillation and the impact of distillation on the lees.

3. Wood and barrels used for cognac.

4. Aging conditions for cognac.

5. The strange exception of early landed cognac.

6. Dilution and Additives in Cognac.

Dilution in Cognac

As mentioned in an earlier post, dilution in cognac does not necessarily come all at the end just before bottling. Diluting alcohol with water is actually an exothermic reaction – it creates heat. And heat blows off more volatile aromas. Much of what is done in cognac's gentle handling is specifically designed not to blow off volatile aromatics.

So cognac is often diluted slowly over the years – a little bit more water is added at certain intervals during aging, and a final amount at the end before bottling (well, most likely while marrying the blend that will rest before bottling). According to Cognac by Nichos Faith, they don't bring it down below 55% ABV while aging though, as it needs to be stronger to interact with the wood in the barrel. (Cognac is distilled to 70% initially and at least at Hine they dilute to 62-65% before putting it in barrels.)

The water used for dilution at Hine is reverse osmosis filtered totally neutral water so that there is no flavor impact on the spirit.

Some producers, however, dilute with petits eaux. Petits eaux ("small waters") is made by putting water into an old cask. This will pull some of the alcohol out of the wood and end up at around 20% ABV after six months, according to Cognac. This water is used to further slow the rate of dilution. [Note that in most places it is spelled "petites eaux," just not in the Cognac book.]

Faith's book says petits eaux are used by "reputable" producers, but Hine's Forget says they do not use petits eaux because "There is a negative impact in term of finesse."

Another reason to dilute cognac slowly is saponification – if not done correctly, the brandy can take on soapy flavors, as Faith writes, "When brandy is blended with water, molecules of fatty acids clash and the result is the sort of cheap, soapy cognacs found in all too many French supermarkets."

I would love some time to compare quick-diluted soapy-cognac with properly-reduced version to see how soapy soapy cognac is.

Boisé

Some call boisé cognac's dirty secret. It is woody water made from boiling wood chips down into a thick liquid. This liquid is added to cognacs to make them woodier without the cost of new wood barrels. As Faith writes, "It thus provides a shortcut for those wanting to add a touch of new wood to their cognacs – and an alternative to buying new casks which now cost up to £500 each, which equates to over a pound per bottle of cognac. "

Forget says that boisé is often used in wine production (I had no idea, but it makes sense), but Hine does not use it in their cognac. Faith writes that there is no limit on boisé used in cognac, unlike other additives.

I wonder about making some boisé at home to make "barrel-aged" cocktails without the barrel…. I'll have to think about that next time I get some wood chips.

Sugar

According to Faith, it is permissible to add up to 8 grams of sugar per liter to cognac, and certainly it is very common to add sugar especially to young cognacs. In the case of Hine, Eric Forget says their VSOP and XO expressions do have added sugar, but not the rest of the line. He says, "It is a common habit for all houses to deliver a little sweetness."

Caramel

Coloring caramel, which should be flavorless, is a common additive not just in cognac but scotch whisky, rum, tequila, and pretty much all aged beverages except straight bourbon where it is not allowed.

Most producers will say that adding caramel is for "consistency only" and not to make the products appear older by being darker, but in cognac some producers are actually honest about it. For Chinese/Japanese markets in particular cognacs are often made darker than the same cognacs sold elsewhere. (Nicholas Faith writes that they are often made "richer" as so they can be diluted with ice as they are frequently consumed.)

Forget says that Hine does not make their products for other markets extra dark.

Filtration

Forget says Hine is filtered, "Like all the houses of cognac, at room temperature and then again at cool temperature. Cognac is very rich in oils and if some are [removed] during the filtration, and if the filtration is well conducted, there is no negative impact on the quality. It is also necessary to export in cold regions."

Typically spirits below 46% ABV are chill-filtered for just this reason – when the spirits get cold, oils can come out of solution and look cloudy. Consumers, generally speaking, associate this with the spirit being bad or moldy or something; and cognac is nearly always bottled at 40% ABV, so all cognac (that I know about anyway) is chill filtered. Forget says this is only done for visual reasons.

If you ever want to see the effect, take a 46% or higher spirit (probably whiskey) and add some cold water to dilute it a bit. Place a glass of this and a glass of full-strength spirit in the freezer and compare after they chill – you can see the cloudy bits in the diluted one.

Marriage

I did not ask Forget specific questions about how long after creating blends does the cognac sit in large vats to "marry," to come into harmony with itself so that it doesn't taste disjointed. (To be fair, I'd already asked him 100 questions at this point.)

But when I inquired if I'd missed anything or if anything else could impact the blending process, he said two factors I hadn't mentioned were having bad wood (which is a problem I think we're seeing in all the small batch American whiskies – people are so concerned with distilling they forget to pay attention to the barrels); and the other potential problem is not allowing enough time for marrying the blend before bottling.

So, this is the last official post in the series sponsored by Hine cognac. I've learned so much, and yet I still have so many questions! But that's the nature of learning - you're never done, it's always a journey. I hope you were also able to enjoy the ride.

Note: This series of posts has been sponsored by Hotaling & Co, importers of Hine cognac.