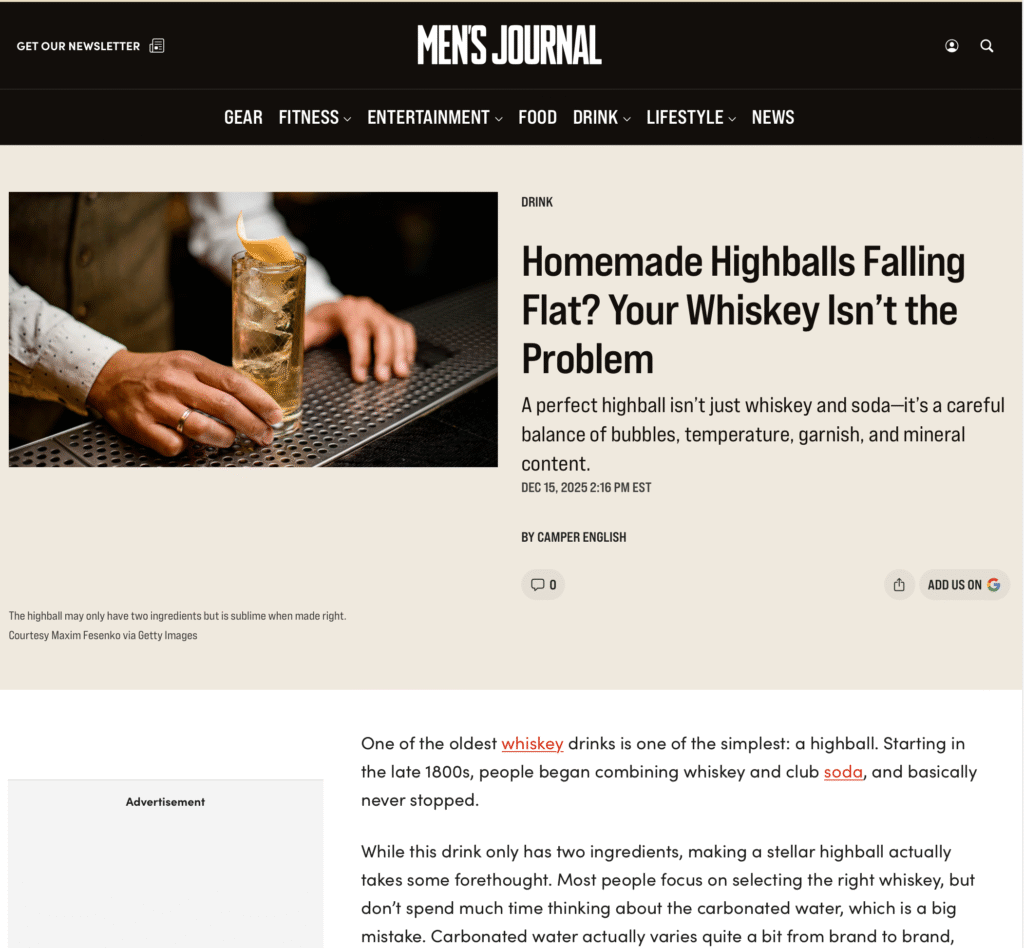

For Men’s Journal, I wrote about the choice of sparkling water for your whiskey highball.

Read it here.

For Men’s Journal, I wrote about the choice of sparkling water for your whiskey highball.

Read it here.

My fellow drink writer Liza Weisstuch wrote a story about seltzer and the specific affinity that the jewish people of NYC have for it.

The story includes some quotes from me, as I covered the medicinal history of spas and the soda fountain in my book Doctors and Distillers.

The story is very fun and super interesting – read the whole thing here.

My latest piece for Food & Wine is "How a Bottled Water Goes Social Media Viral and the Real Differences Between Them"

The reporter for this story in The Guardian and I talked a long time about clear ice, iceberg water, and bottled water.

Not much made it into the final story from me (so it goes) but I did get mentioned in the lead paragraphs!

Towards the end of 2009, Camper English achieved a major breakthrough in his kitchen in San Francisco. After months of experimentation, English, a drinks industry consultant, created the perfect piece of clear ice: a cube with minimal fissures and microbubbles, as transparent as air.

His method for making clear ice – freezing water in an insulated container, which forces tiny bubbles towards the edge and leaves the rest of the block clear – is now widely copied in bars. English has also written The Ice Book: Cool Cubes, Clear Spheres, and Other Chill Cocktail Crafts, and has found his algorithmic niche as Instagram’s top “ice cube reporter”. He regularly shares pictures of bevelled spheres, ridged gems and crystalline pebbles on his account @alcademics, all tagged with #IceBling.

The story has some good points – the most important one being that bottled water does not compete with tap water.

But anyway, if you want to geek out about water with me, I have an upcoming water class in April 2024 you can join!

I recently read the 2012 book Drinking Water: A History by James Salzman, in preparation for my forthcoming water classes I'm teaching in San Francisco.

It is about the history of public and private drinking water and bottled water, from olden times until recent times. From researching Doctors and Distillers I already knew a lot of information in this book, but it deepened my understanding of some things.

Here are some facts I picked up.

Roman Lead Poisoning

You know how people theorize lead poisoning might have killed off the Roman Empire? Well if so, the lead likely didn't come from the lead pipes, even though those were used to carry water- in part because they became calcified and the water wouldn't touch the lead. But they did boil fermented grape juice into a syrup called sapa for sweetening foods and beverages, since they didn't have sugar yet. The boiling was often done in lead pots, and it was this source of lead poisoning that could have led to problems.

p. 71

Montezuma's Revenge

Traveller's belly was known by different names in different parts of the world. Montezuma's Revenge, Delhi Belly, Mummy Tummy (Egypt), and Karachi Crouch (Pakistan). It's not neccesarily that the water is so bad, it's that you're not used to it.

p. 76

Chlorinated Water

Chlorinated Water dates to 1902 – the first municipality to use it was Middelkerke, Belgium. In 1908 Jersey City became the first city in the US to do so for an entire city.

Drinking Fountains

Public drinking fountains were often sponsored as charity works by pro-Temperance groups, both in England in the 1800s and in the US leading up to Prohibition. They were provided as free alternate sources to beer, which was the more common form of hydration before modern sanitation. Still, many public drinking fountains had a community cup chained to them for drinking! A lot of people got sick from the cups. The modern "bubbler" with water that shoots out so that you don't need a cup was an answer to the communal cup.

Some early drinking fountains in the US had space to add 20 pound blocks of ice to chill the water.

Branded Water

The first branded bottled waters were from holy wells during the era of European religious pilgrimages and visits to holy sights and relics. One could purchase flasks that were branded with the source. Later on, healing mineral waters became the branded bottled waters.

p 168

Modern Bottled Water Brand Dates

Poland Spring 1845

Vittel 1855

Perrier 1863

Deer Park 1873

Arrowhead 1894

p 171

Bottled Tap Water

For Dasani and Aquafina, "Coke and Pepsi take tap water; run it through a series of fine filters to remover minerals and bacteria, ultraviolet and ozonation treatments to kill any remaining organisms, and reverse osmosis to remove any remaining materials; and then add minerals back in because all the taste has been removed."

p 178

US FDA Regulated Terminology

I don't think I knew that certain terms on bottled water bottles are regulated. I verified on the FDA website:

The agency classifies some bottled water by its origin. Here are four of those classifications:

- Artesian well water. This water is collected from a well that taps an aquifer—layers of porous rock, sand, and earth that contain water—which is under pressure from surrounding upper layers of rock or clay. When tapped, the pressure in the aquifer, commonly called artesian pressure, pushes the water above the level of the aquifer, sometimes to the surface. Other means may be used to help bring the water to the surface.

- Mineral water. This water comes from an underground source and contains at least 250 parts per million total dissolved solids. Minerals and trace elements must come from the source of the underground water. They cannot be added later.

- Spring water. Derived from an underground formation from which water flows naturally to the surface, this water must be collected only at the spring or through a borehole that taps the underground formation feeding the spring. If some external force is used to collect the water through a borehole, the water must have the same composition and quality as the water that naturally flows to the surface.

- Well water. This is water from a hole bored or drilled into the ground, which taps into an aquifer.

Monitoring Water

“One thing is certain: Bottled water is less stringently regulated than tap water.” Bottled water isn't necessarily more "pure" or safe than tap water. It certainly can be though.

p 183

I provided some context for a story about carbonated water for Wine Enthusiast.

“Naturally carbonated mineral spring water was thought to be extra healthy compared with regular mineral water, and far healthier than surface water from rivers and streams,” English notes. “European and American mineral springs rich in iron or other mineral salts were recommended to settle the stomach or treat conditions including anemia.”

Many distilleries brag about their pure water supply, but typically that water is only used for fermentation, and then reverse osmosis filtered or distilled tap water is used to dilute spirits down to bottle proof. So the quantity of that special water left in the bottle is small – in the case of vodka it's just a few percent.

Some producers claim to use special water but then do the RO or distillation to it to remove minerals and other organic matter from it for bottling, making the special water a lot less special.

That's what I suspected was going on when I noticed that on the new Lucky Thirteen bottling from Widow Jane bourbon the label says, "Pure limestone water from the legendary Rosendale mines of NY."

So I asked their PR team for clarification- it would be pretty unusual to be using untreated/filtered water.

I heard back from Lisa Wicker, President and Head Distiller for Widow Jane. She wrote:

It is very unusual to use mineral-rich water for proofing! When I “inherited” proofing using water from the Rosendale limestone mines, it took me a while to determine how to handle it. We worked with water engineers on a withdrawal system that does not strip the minerals. The water tests beautifully, it does not need to be treated. Our cave is under lock and key for purity and we hold the only permit of its' kind in New York for withdrawing cave water as an ingredient. Finally, we “polish” the whiskey without chill and conventional filtration, which would have stripped the minerality out that makes Widow Jane whiskey, “Widow Jane.”

So, it turns out that they do something that I think is pretty unique. I will have to see if I can detect any mineralogy when I taste it.

I was recently in touch with Top Note Tonic founders founders Mary Pellettieri and Noah Swanson about their new Club Soda that was created specifically for making highballs with whiskey. They went into the process with specific goals in mind to pair it with whiskey, researched styles of water and other brands' mineral content, then experimented with specific minerals to use for best results.

The end product contains water, potassium bicarbonate, sodium bicarbonate, calcium chloride, magnesium sulfate, and salt.

To achieve their ideal club soda, Pellettieri says that they followed "standard beer chemistry rules – to make malty beer the brewer will add chloride ions and have a 2:1 chloride:sulfate content minimum. The goal was to make it high chloride, low sodium. [Other brands] didn’t take a position on what a club is. It was time to make club soda different, not just salty water. "

To achieve their ideal club soda, Pellettieri says that they followed "standard beer chemistry rules – to make malty beer the brewer will add chloride ions and have a 2:1 chloride:sulfate content minimum. The goal was to make it high chloride, low sodium. [Other brands] didn’t take a position on what a club is. It was time to make club soda different, not just salty water. "

"We really followed beer brewing fundamentals and built our club soda water base to amplify malt, like a beer brewer would do to make a light malty beer. It so happens the core ion, chloride, is what we focused on here. I think this reference is the best to explain the different mash water chemistry and the impact to beer across the world.

https://www.brewersfriend.com/brewing-water-target-profiles/

"In brewing, they look at the ions separately, and focus on ratios. SO4/Cl ratio is an important one, as is the hardness and alkalinity of the water. They all play a factor in the final product, because of how the malt interplays with the mash."

But water of this style is also similar to Kentucky limestone water. "Noah found after researching that it was close to Kentucky water. We found out indeed Kentucky water was close, but not exact to what we set out to do. We focused on the mineral content, keeping it low sodium, but high in calcium, magnesium and minerals that amplify flavor."

Differentiation

Pellettieri says, "The chloride helps pop the citrus [notes], so it plays nice with vodka too. It's probably not best in a bitter drink."

They had other brands of club soda analyzed.

Swanson says, "[We looked at] a few waters from Japan –those were also low sodium, but some were also low in other minerals."

Pellettieri says, "Mineral waters are variable, so the numbers change a bit…. Schweppes is hugely salty. Q is salty. Our target was 54, a little lower than Fever Tree. I think later in the game we decided to add more potassium – it adds some mouthfeel. But too much potassium chloride gave it a swimming pool character. Topo Chico is high in sulfate. So is San Pellegrino – it almost has an eggy character from sulfate [sulfur]."

I asked about Burton Water Salts, which are a pre-mixed ratio of minerals that are used to make beer, but they also closely resemble the mineral ratios in San Pellegrino.

Pellettieri responded, "Burton salts famously produce really hoppy beer and we didn't follow that sort of chemistry. We followed the rules for making 'light/malty' beer as the image below shows. You can see the light hoppy beer water chemistry formal below as well, it has nearly 3:1 So4/Cl. Brewing research shows the higher the SO4, the higher the hop perceptions. Even 4:1 is what they strive for. But we were not going for that."

Carbonation

Swanson said of carbonation, "We did a lot of whisky highballs in the office. [We were aiming for] a subtle mouthfeel, super bright carbonation to lift the maltiness of whiskies."

"Our goal was 4.0 volumes. Most beer is 2.5-2.8 volumes. Champagne can be 6.0."

I don't recall if they had other brands measured for carbonation level. I asked if it is possible to get that high carbonation in cans versus bottles. They told me it's challenging to reach high carbonation levels in cans by nature of canning and the large surface area of the top of a can, versus bottles.

Production and The Future

Swanson says, "Our co-packer packs with 100% RO [mineral-free reverse osmosis-filtered] water. Other ones only use a portion of RO water. So that was a problem with others. [Our co-packer] mixes minerals into water then dilutes with more water [before force carbonating]."

I asked – since this is "Top Note Club Soda No 1, aka 'Kentucky Club" if that means there are plans for this to be a range of club sodas. Yep, there are.

Pellettieri says they're, "Planning to do a series of them – low and higher sodium sodas: High sodium for more bitter drinks [like bitters and soda]; lower for malty more subtle. A little sodium goes a long way."

DIY at Home

Are you curious about making your own custom soda water at home? A few years back I did some experiments I called The Water Project. The most relevant posts are:

In a series of posts I've been nerding out about cognac production, after sending a list of 100 questions to Hine cognac's cellar master Eric Forget, and combining that information with what I can pick up in books and elsewhere.

In this post, I'll talk about diluting and additives used in cognac. There is a lot that happens in between taking cognac out of a barrel and it being sealed up in a bottle.

The posts in this series are:

1. Cognac from grapes to wine.

2. Cognac distillation and the impact of distillation on the lees.

3. Wood and barrels used for cognac.

4. Aging conditions for cognac.

5. The strange exception of early landed cognac.

6. Dilution and Additives in Cognac.

Dilution in Cognac

As mentioned in an earlier post, dilution in cognac does not necessarily come all at the end just before bottling. Diluting alcohol with water is actually an exothermic reaction – it creates heat. And heat blows off more volatile aromas. Much of what is done in cognac's gentle handling is specifically designed not to blow off volatile aromatics.

So cognac is often diluted slowly over the years – a little bit more water is added at certain intervals during aging, and a final amount at the end before bottling (well, most likely while marrying the blend that will rest before bottling). According to Cognac by Nichos Faith, they don't bring it down below 55% ABV while aging though, as it needs to be stronger to interact with the wood in the barrel. (Cognac is distilled to 70% initially and at least at Hine they dilute to 62-65% before putting it in barrels.)

The water used for dilution at Hine is reverse osmosis filtered totally neutral water so that there is no flavor impact on the spirit.

Some producers, however, dilute with petits eaux. Petits eaux ("small waters") is made by putting water into an old cask. This will pull some of the alcohol out of the wood and end up at around 20% ABV after six months, according to Cognac. This water is used to further slow the rate of dilution. [Note that in most places it is spelled "petites eaux," just not in the Cognac book.]

Faith's book says petits eaux are used by "reputable" producers, but Hine's Forget says they do not use petits eaux because "There is a negative impact in term of finesse."

Another reason to dilute cognac slowly is saponification – if not done correctly, the brandy can take on soapy flavors, as Faith writes, "When brandy is blended with water, molecules of fatty acids clash and the result is the sort of cheap, soapy cognacs found in all too many French supermarkets."

I would love some time to compare quick-diluted soapy-cognac with properly-reduced version to see how soapy soapy cognac is.

Boisé

Some call boisé cognac's dirty secret. It is woody water made from boiling wood chips down into a thick liquid. This liquid is added to cognacs to make them woodier without the cost of new wood barrels. As Faith writes, "It thus provides a shortcut for those wanting to add a touch of new wood to their cognacs – and an alternative to buying new casks which now cost up to £500 each, which equates to over a pound per bottle of cognac. "

Forget says that boisé is often used in wine production (I had no idea, but it makes sense), but Hine does not use it in their cognac. Faith writes that there is no limit on boisé used in cognac, unlike other additives.

I wonder about making some boisé at home to make "barrel-aged" cocktails without the barrel…. I'll have to think about that next time I get some wood chips.

Sugar

According to Faith, it is permissible to add up to 8 grams of sugar per liter to cognac, and certainly it is very common to add sugar especially to young cognacs. In the case of Hine, Eric Forget says their VSOP and XO expressions do have added sugar, but not the rest of the line. He says, "It is a common habit for all houses to deliver a little sweetness."

Caramel

Coloring caramel, which should be flavorless, is a common additive not just in cognac but scotch whisky, rum, tequila, and pretty much all aged beverages except straight bourbon where it is not allowed.

Most producers will say that adding caramel is for "consistency only" and not to make the products appear older by being darker, but in cognac some producers are actually honest about it. For Chinese/Japanese markets in particular cognacs are often made darker than the same cognacs sold elsewhere. (Nicholas Faith writes that they are often made "richer" as so they can be diluted with ice as they are frequently consumed.)

Forget says that Hine does not make their products for other markets extra dark.

Filtration

Forget says Hine is filtered, "Like all the houses of cognac, at room temperature and then again at cool temperature. Cognac is very rich in oils and if some are [removed] during the filtration, and if the filtration is well conducted, there is no negative impact on the quality. It is also necessary to export in cold regions."

Typically spirits below 46% ABV are chill-filtered for just this reason – when the spirits get cold, oils can come out of solution and look cloudy. Consumers, generally speaking, associate this with the spirit being bad or moldy or something; and cognac is nearly always bottled at 40% ABV, so all cognac (that I know about anyway) is chill filtered. Forget says this is only done for visual reasons.

If you ever want to see the effect, take a 46% or higher spirit (probably whiskey) and add some cold water to dilute it a bit. Place a glass of this and a glass of full-strength spirit in the freezer and compare after they chill – you can see the cloudy bits in the diluted one.

Marriage

I did not ask Forget specific questions about how long after creating blends does the cognac sit in large vats to "marry," to come into harmony with itself so that it doesn't taste disjointed. (To be fair, I'd already asked him 100 questions at this point.)

But when I inquired if I'd missed anything or if anything else could impact the blending process, he said two factors I hadn't mentioned were having bad wood (which is a problem I think we're seeing in all the small batch American whiskies – people are so concerned with distilling they forget to pay attention to the barrels); and the other potential problem is not allowing enough time for marrying the blend before bottling.

So, this is the last official post in the series sponsored by Hine cognac. I've learned so much, and yet I still have so many questions! But that's the nature of learning - you're never done, it's always a journey. I hope you were also able to enjoy the ride.

Note: This series of posts has been sponsored by Hotaling & Co, importers of Hine cognac.

Several years ago I visited the Deanston and Bunnahabhain scotch whisky distilleries. Click on those words to read about the visits.

At the time I was there I was really obsessed with the effects of water in distilled spirits (not that I'm over it), so I followed up with some super specific questions about the pH and TDS of the water sources. I never ended up putting up a blog post about it but now it's about time.

Note that the Highland and Islay distilleries have slightly basic water (above 7.0), while the Island of Mull distillery water is slightly acidic. It would be more typical for Islay water to be acidic, as it typically runs through decaying vegetation through peat bogs, but at Bunnahabhain they collect the water upstream, two miles from the distillery. (Read more here.)

Deanston (Scottish Highlands slightly north of Glasgow)

Water Source: River Teith

Ph 7.1

Total Hardness ( mg CaCO3/ L ) 19.5

Colour (mg/L Pt/Co scale ) 20

Calcium ( mg/L ) 6.18

Bunnahabhain (Islay)

Water source: Margadale underground river

Ph 7.2

Total Hardness 120.7

Colour 50

Calcium 29.5

Tobermory (Isle of Mull)

Water Source: Gearr Abhainn

Ph 6.2

Total Hardness 21.4

Colour 175

Calcium 5.02.

To see how these water sources compare against typical Highland/Islay water, see this post as well as the whole Water Project series here to see how different water sources change the flavor of whisky before and after distillation.