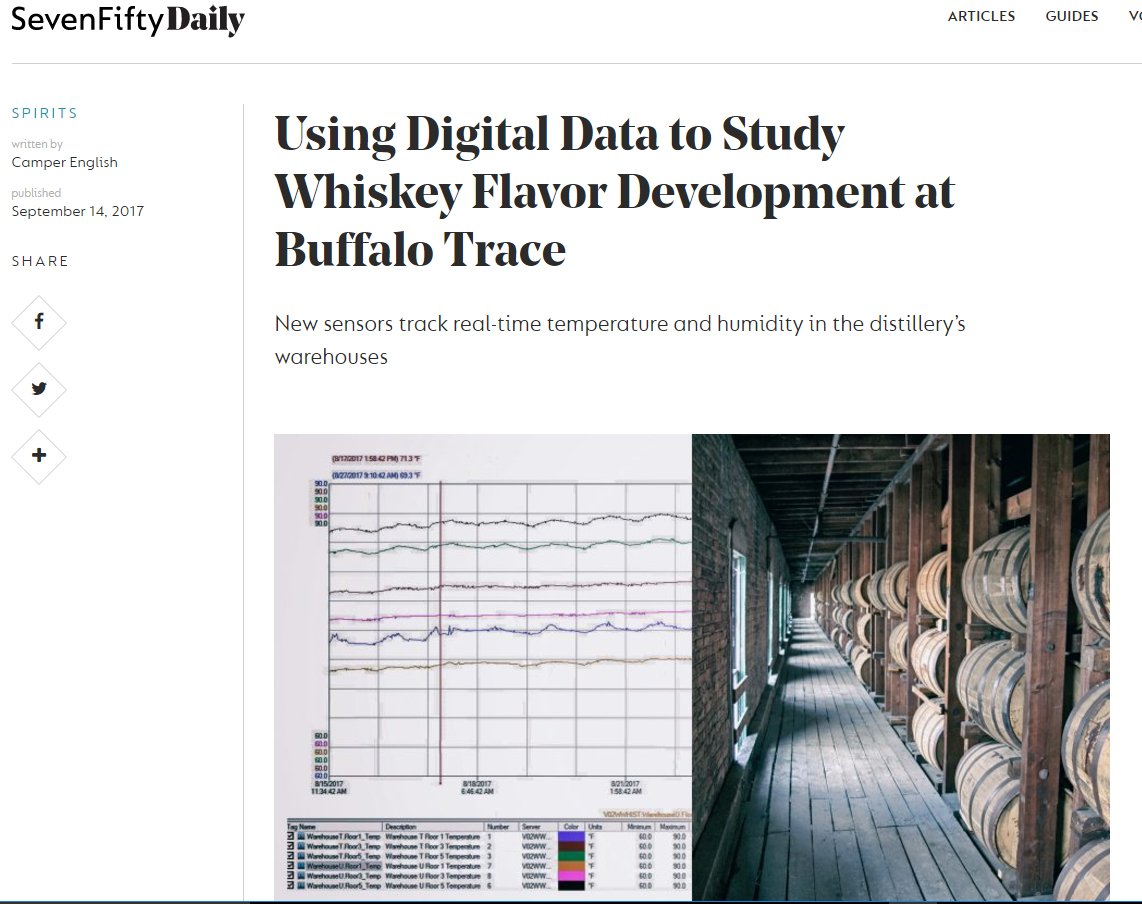

In my latest story for SevenFifty Daily, I wrote about new temperature and humidity sensors installed in warehouses at Buffalo Trace, and what those could mean for studying aging of spirits and adjusting future blends.

Category: whisky

-

Phylloxera, Gin, and Scotch Whisky

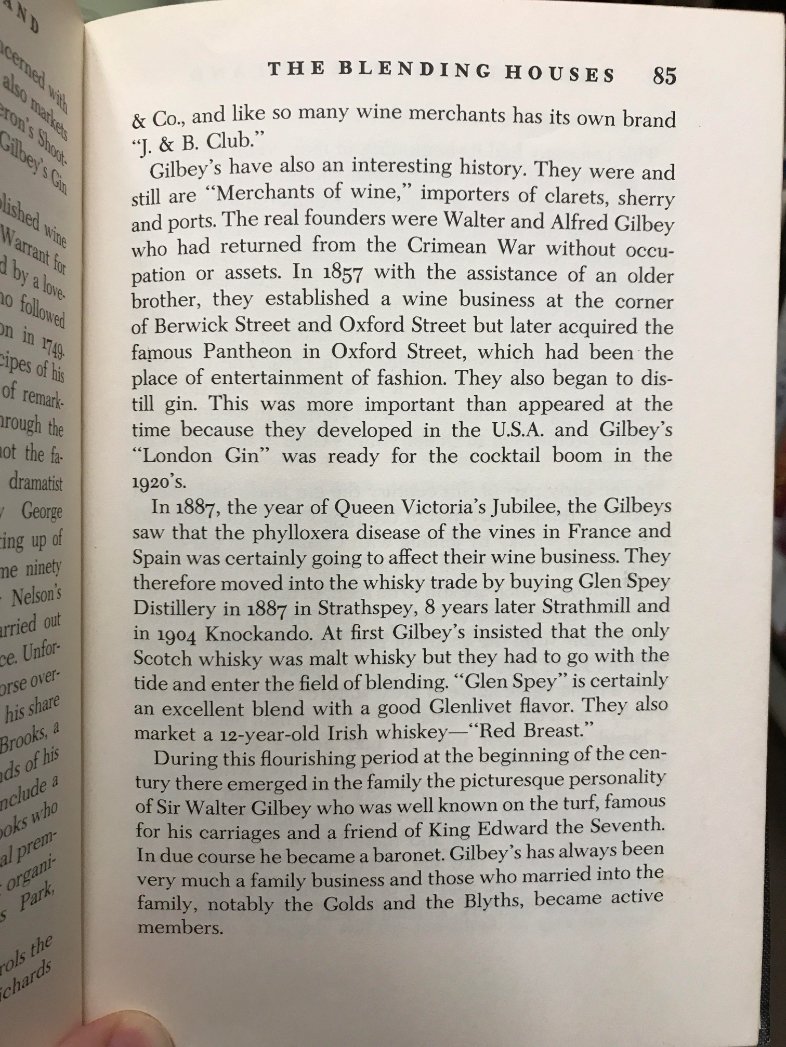

I'm continually researching topics related to bugs and booze, and went looking for some better information on how scotch whisky sales were affected by the phylloxera plague that took down most of Europe's vines in the late 1800s.

Many sources cite that scotch whisky sales really took off in the same time period as phylloxera killed the wine biz as people switched to spirits, and I was looking for more solid information on that: sales numbers, etc.

I've found that it's true there was a huge scotch boom in this period (30+ new distilleries opened between 1880-1900), but I was seeking more information.

Anyway, my office is located above the spectacular Mechanics Institute Library, a membership library dating back to 1854. I have plenty of whisky books in my office, but the library itself has some unique books I've not seen elsewhere. I went to see what I could learn.

I happened across a book called The Whiskies of Scotland by RJS Mc Dowall from 1967. It didn't have any information on phylloxera except for this one fun fact about the Gilbey's wine/gin company: they saw phylloxera happening so invested in scotch whisky. Smart.

Today Gilbey's is owned by Beam Suntory.

Anyway, just thought I'd share.

-

Water Chemistry at Deanston, Bunnahabhain, and Toberymory Distilleries

Several years ago I visited the Deanston and Bunnahabhain scotch whisky distilleries. Click on those words to read about the visits.

At the time I was there I was really obsessed with the effects of water in distilled spirits (not that I'm over it), so I followed up with some super specific questions about the pH and TDS of the water sources. I never ended up putting up a blog post about it but now it's about time.

Note that the Highland and Islay distilleries have slightly basic water (above 7.0), while the Island of Mull distillery water is slightly acidic. It would be more typical for Islay water to be acidic, as it typically runs through decaying vegetation through peat bogs, but at Bunnahabhain they collect the water upstream, two miles from the distillery. (Read more here.)

Deanston (Scottish Highlands slightly north of Glasgow)

Water Source: River Teith

Ph 7.1

Total Hardness ( mg CaCO3/ L ) 19.5

Colour (mg/L Pt/Co scale ) 20

Calcium ( mg/L ) 6.18

Bunnahabhain (Islay)

Water source: Margadale underground river

Ph 7.2

Total Hardness 120.7

Colour 50

Calcium 29.5

Tobermory (Isle of Mull)

Water Source: Gearr Abhainn

Ph 6.2

Total Hardness 21.4

Colour 175

Calcium 5.02.

To see how these water sources compare against typical Highland/Islay water, see this post as well as the whole Water Project series here to see how different water sources change the flavor of whisky before and after distillation.

-

Lunch in a Teepee, Dinner in a Castle: A Luxe Trip to The Glenlivet

Two years ago I went on a quick press trip with The Glenlivet single malt scotch whisky for the release of the first Winchester Collection, a series of 50-year-old whiskies from the brand. It was a vintage 1964 release.

Two years ago I went on a quick press trip with The Glenlivet single malt scotch whisky for the release of the first Winchester Collection, a series of 50-year-old whiskies from the brand. It was a vintage 1964 release.While on the visit we were also able to taste the 1966 vintage that has recently come out and is the second bottling of the collection.

As this has just hit the market, I decided it was a good time to revisit my visit. Those notes are below.

The press release describes the new release:

The Vintage 1966 is the second release from Winchester Collection, The Glenlivet’s first ever series of rare and precious 50-year-old single malt Scotch Whiskies.

The Vintage 1966 is a precious whisky that uses sherry casks to enhance the trademark soft, sweet and sumptuous complexity that The Glenlivet is best known for. The result is a remarkable single malt that layers the soft, smooth notes of The Glenlivet with delicate taste of spice – a teasing intermingling of cinnamon and liquorice – and offers an exceptionally long, smooth finish with a pleasing hint of dryness.

The Vintage 1966 is a precious whisky that uses sherry casks to enhance the trademark soft, sweet and sumptuous complexity that The Glenlivet is best known for. The result is a remarkable single malt that layers the soft, smooth notes of The Glenlivet with delicate taste of spice – a teasing intermingling of cinnamon and liquorice – and offers an exceptionally long, smooth finish with a pleasing hint of dryness.Only 100 bottles of remarkable Speyside single malt, priced at $25,000 each, have been carefully guarded and cared for by generations of The Glenlivet Master Distillers and are currently on sale around the world in limited distribution.

An Afternoon Trip along the Smuggler's Trails

The hills and fields around The Glenlivet distillery has a series of walking trails called The Smugglers Trails, in tribute to the tradition of pre-legal distilling in the area. We had a day of activities leading up to the distillery visit, and then a dinner evening at a local castle. As one does.

In the afternoon we rode ATVs around the countryside, with a view of The Glenlivet distillery off in the valley. We had a picnic in a giant portable teepee (as one does), and enjoyed a display of falconry (as is typical).

The Glenlivet Distillery Visit (Nerd Stuff)

Next we headed downhill toward the distillery located in the middle of the valley. Though Glenlivet is the first licensed distillery in the Highlands (in 1824), this is the second location of the distillery after the first one burned down. The second was erected in 1858.

We first stopped at Josie's Well, one of the many wells used as a water source for fermentation at the distillery. The waters from the various wells are blended before use. Alan Winchester (for whom the Winchester Collection is named) says that The Glenlivet is a hard water distillery.

On the way into the distillery, we pass a duck pond that is used to cool the condenser water coming off the still- and I'm sure the ducks enjoy a warm pond to swim in.

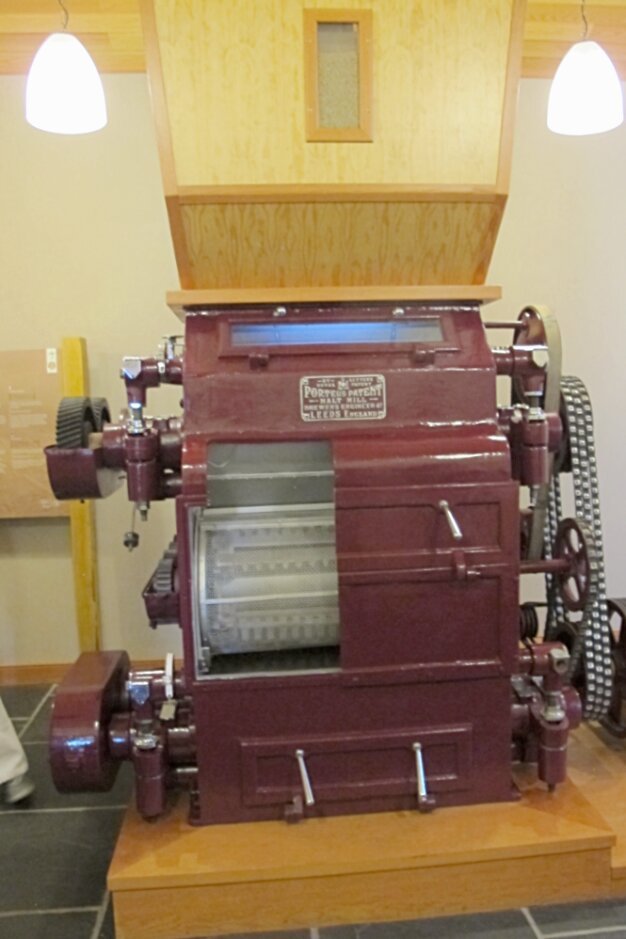

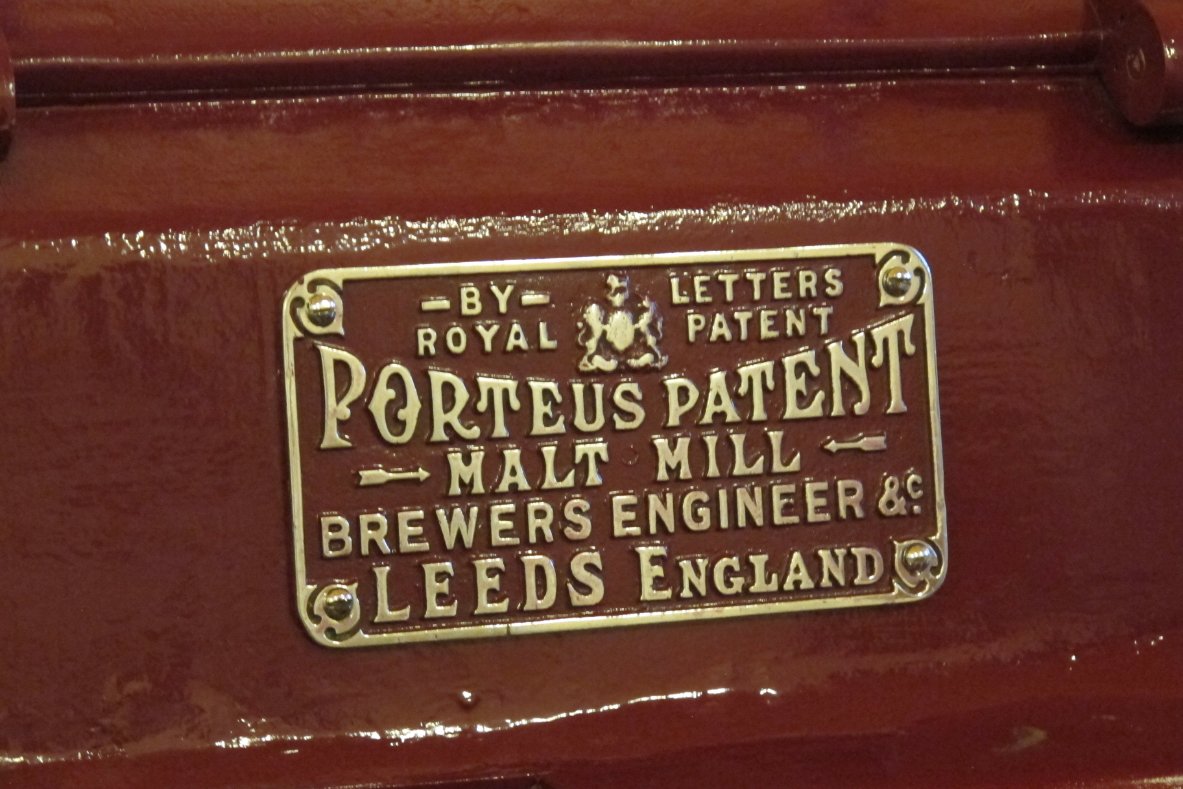

Barley for the whisky is purchased from Scotland and abroad, and it is (as you'd guess from the soft and fruity flavor profile) unpeated. Winchester says the grind of the barley determines a lot of the final whisky flavor too – a point I'd not heard many distillers discuss (versus just maximum alcohol extraction). I'd like to investigate this more in the future.

For every ton of barley that comes into the distillery, one third ends up as whisky, another third as CO2 fizzed off by fermentation, and the final third is spent solids sold as cattle feed.

After the barley is ground, it goes to the mash tun where it is washed three times with hot water to pull out all the fermentable sugars. They don't stir it before pulling off the clearest liquid here, as this produces a less cereal-flavored (and presumably more fruity-flavored) whisky.

Next the clear liquid is transferred to the Oregon wood wash backs for fermentation. After 50 hours it reached about 8.5% ABV.

There are 14 stills at The Glenlivet, not just the six pretty ones you see on the tour. A lot happens out of sight or off-site, given that the distillery is relatively small. This is the second best selling single malt scotch whisky brand so they produce a lot here. There are aging warehouses located around Scotland, and things like watering down to barrel proof also happen elsewhere.

Demineralized water is used both for barrel proofing and for bottle proofing, as is typical.

Aging takes place in ex-bourbon, ex-sherry, "traditional" (reused) barrels, and new French oak barrels.

Dinner in a Castle

After sampling a couple of 50-year-old whiskies at the distillery, a castle was a natural choice for dinner. It helps that there are a lot of castles around.

But the castle that we ended up in is Fyvie Castle, which dates back to at least 1211. We had bagpipes, suits of armor, the whole shebang.

It was a nice way to end a quick-and-lovely trip to The Glenlivet.

-

Distillery Visit: Stranahan’s Colorado Whiskey in Denver

This December, I visited the Stranahan's single malt Colorado whiskey distillery in Denver, in order to partake in the fun and insanity of waiting in line overnight for the annual Snowflake whiskey release.

This December, I visited the Stranahan's single malt Colorado whiskey distillery in Denver, in order to partake in the fun and insanity of waiting in line overnight for the annual Snowflake whiskey release. The previous night, however, we were given a tour by Stranahan's distiller Rob Dietrich.

Background

Stranahan's was launched by Jess Graber, who along with George Stranahan came up with the original recipe and product launch. This was back in 2004-2006, and in 2010 the brand was sold to Proximo (created by Jose Cuervo and owner of stylishly-branded brands including The Kraken rum and Boodles Gin).

In Denver, there is clearly no animosity towards Proximo's ownership, as the Snowflake whiskey release events show. Likewise, Jess Graber's newer whiskey brand TinCup is "finished" at Stranahan's (and I believe owned by Proximo), so that relationship remains in good standing as well.

Production

Stranahan's is an American single-malt, meaning it's distilled from 100% malted barley. The barley they use is mostly a "bulk" barley, plus three other "specialty" barleys making up their custom recipe.

The barley is milled on-site, then put into the mash tun to extract sugars for fermentation. Water is added. Next it goes into a "boil kettle" that kills bacteria/sterilizes it basically. This is not typical in bourbon or scotch production, but comes from the facility's historical use as a brewery. This is the stage at which hops would have been added.

I'm guessing that between what they call the mash tun and the boil kettle, it's doing the same thing as the mash tun and wash back of scotch whisky (soaking the grains and washing out the fermentable sugars with hot water), minus the filtering of the liquids (which at Stranahan's comes in the next step).

Then it goes into a "whirlpool," another brewery tool, which spins it to separate the liquids from the solids and gets "clean distiller's wort" out of it.

Fermentation is in closed-top, temperature-controlled stainless steel fermenters that are 5500 gallons in size. These also come from the former brewery. The yeast Dietrich says is an unusual strain, chosen not for producing high alcohol content necessarily, but for flavor production. Fermentation lasts six days. The ABV after fermentation? They won't say.

Interestingly, the water they use for fermentation is charcoal-filtered city water, while the water they use to dilute post-distillation to barrel-proof and bottle-proof is Colorado Springs mineral water. Typically, it's the other way around – the "special" local water is used for fermentation, then the reverse osmosis filtered city water is used for the rest. Interesting.

After fermentation, they suck out everything except the spent yeast and keep it in the "wash storage" until they're ready to distill it.

There are three large wash stills. One is the distillery's first still that they used to use for everything. They've since expanded to three wash stills for the first distillation, and two smaller spirit stills for the second distillation (as there is less volume of liquid to distill after the first distillation is done).

As you can see, both sets of stills are pot-column hybrid stills. If I recall correctly, Dietrich said their hybrid still was the first of its type used to make whisky in the state.

After the first distillation the spirit is 40%, and the spirit comes off the second distillation at 150 proof (75% ABV).

The spirit is then diluted with water from Colorado Springs and put into the barrels at 110 proof (55%). Amazingly, this spring water for barrel and bottle proofing is El Dorado Springs water, purchased in 5-gallon bottles, same as you'd buy for the water cooler in your office. There was a huge rack of them in the distillery. So I guess if you wanted to make matching ice cubes or bourbon and branch water, you'd know exactly which water to use.

In Colorado's weather, the alcohol percentage rises in the barrel, so after 2-3 years it comes out of the barrel at 114-166 Proof. The barrels are all new oak barrels, toasted first then charred with #3 alligator char by Independent Stave.

After aging, the spirit is put through a 5-micron filter just to keep out barrel char, then diluted with water from Colorado Springs for bottling. None of the whiskies are chill-filtered.

Stranahan's Whiskeys

The three Stranahan's releases are distilled the same way – same recipe and process. The difference between them is in age and finishing.

The Stranahan's Original single-malt is aged a minimum of two years in new American oak barrels. The majority of the liquid is two years old, with some 3-, 4-, and 5-year whiskey blended in.

The Stranahan's Diamond Peak is all aged four years in new American oak barrels.

The Snowflake whiskies are annual releases first aged in new American oak barrels, then finished in a variety of casks that held other wines/spirits and blended. Those are available for one day and then gone for the year.

-

I Waited in a Long Line for Whiskey, or, A Heroic Tale of Endurance

6 AM, December 3, Denver: While using the port-a-potty, my glasses fogged over with the steam rising from my pee. I knew at that moment I had made the right decision.

A couple weeks earlier, I had been invited to the Stranahan's distillery for the release of their annual Snowflake bottling. The press trip would involve a helicopter ride into the snowy mountains and then waiting outside overnight along with hundreds of other people for the whiskey to be released at 8AM.

Cold weather? Heights? Waiting overnight in a line for drinks? These are all things I very much do not like, yet I very much *do* like to be made uncomfortable. Count me in.

Arriving in Denver, we were told the helicopter ride would not be happening due to poor weather. I was relieved and disappointed as you'd expect. The point of the helicopter ride was to visit Crestone Peak – the Rocky Mountain peak after which this year's Stranahan's Snowflake whiskey was named. (Each annual bottling is named for a different peak, and this year is the 100th anniversary of the first successful summit of Crestone.)

Luckily the clever public relations team found a new way to arouse my discomfort, by taking myself and the other journalists on the trip to a western wear store to buy a cowboy hat, and then to perhaps America's least vegetarian-friendly restaurant. Well-played, team.

The store in question is Rockmount Ranch Wear, and there I picked up a snazzy new hat without too much fuss. The restaurant is The Buckhorn Exchange, Denver's oldest restaurant, taxidermy museum, and server of elk and yak meat. While I didn't eat much there, nor have more than one cocktail (their Old Fashioned has ginger ale in it), I did enjoy plenty of whiskey with Stranahan's distiller Rob Dietrich. I peppered him with nerdy distillery questions that I'll talk about in a future post. (post is here)

At 5AM the next morning, we headed out to the distillery and took our place in line. There were already hundreds of people there, in the very, very cold, near-pitch-dark line that wrapped all the way around the distillery then looped around the roads surrounding it.

The point of the trip was to experience this phenomena- the cultish devotion to the brand by locals (and a few people who came from pretty far away). The first person in line was there on Thursday afternoon for the Saturday morning event – and it turns out it's his thing to always be the first in line.

Most "StranaFans" were in small groups of four or so people, huddled together in lawn chairs wearing heavy winter clothing. Many were in sleeping bags, some had space heaters, there were some tents, a lot of people had been drinking, and I would expect that more than a few had partaken in the state's legal marijuana. At five in the morning, though, most of the line was more mellow and sleepy/asleep than wild.

In our group, we had a small tent with a space heater in it, a little boom box, and people to grill up food for us. It was as genteel as you could make it, but damn it was still cold! I had not expected to start drinking whiskey by 5:30AM, but umm, I needed it. By the time I'd get near the end of an ounce and a half or so of whiskey in my tin cup, both the liquid and the cup itself would be uncomfortably cold. (I was also hoping not to use the port-a-potty but after a lot of liquid I needed it, and had embraced my fate.)

Soon enough though, the sun began rising and people started stirring. After a few drinks, our little place in line got a tiny bit loud. Others got up and started stamping their feet to shake off the cold. Eventually towards 7AM or so (forgive me for inaccurate timing reports, I had consumed a fair amount of whiskey at this point), then line started moving.

They handed out tickets for the number of bottles that people wanted to purchase (maximum of two), so that when it reached the point where no more bottles would be available, people would know they'd not bother getting in line.

The fast-motion videos below should give you an idea of just how long the line was.

They began letting people into the distillery, directing the line along probably the longest route through it so that people could warm up while waiting. They had entertainment inside including live bands, and everyone was in a jolly mood at that point. (Not that anyone was in a bad mood at any point… there was a lot of whiskey around.)

The line wriggled all the away around the warehouse and back to the front counter, we were able to purchase our bottles of whiskey and have them signed by distiller Rob Dietrich.

First guy in line I think, walking out with his bounty as we were getting to the front of the building.

First guy in line I think, walking out with his bounty as we were getting to the front of the building.Then, very tipsily, the group of journalists piled into some Ubers with our newly-aquired, hard-earned whiskey, and headed out to a much-needed breakfast. With discomfort, comes success!

About Stranahan's Snowflake Batch 19: Crestone Peak

Each year Stranahan's Colorado single-malt releases a special Snowflake batch (no two are the same- get it?), named for one of the peaks of the Rocky Mountains.

Each year Stranahan's Colorado single-malt releases a special Snowflake batch (no two are the same- get it?), named for one of the peaks of the Rocky Mountains. The whiskey begins as Stranahan's Original (mostly two-year-old single malt with some 3- 4-, and 5- year mixed in) that is finished in a variety of casks. The press release notes, "Rob has chosen to celebrate Crestone Peak – Colorado’s seventh highest summit – by marrying the whiskeys from seven different barrels to create this edition of Snowflake."

The seven barrels in this year's single-malt blend are:

- 1 Syrah Amador wine cask

- 1 Madeira wine cask

- 1 Old Vine Zinfandel wine cask

- 1 Saint Croix Rum cask

- 2 4-year old Stranahan’s whiskey casks

- 1 5-year old Stranahan’s whiskey cask

Of course, the annual Snowflake release is already sold out, so if you didn't get one, you didn't get one.

Read about how Stranahan's makes their whiskey with my distillery visit blog post here.

-

Sulfur Control in Sherry Casks Headed to Midleton Distillery

While in Jerez for the launch of the Redbreast Lustau Edition, I had the opportunity to speak with Midleton Distillery Head blender Billy Leighton. Since I had a couple extra minutes, I asked him about the effect of sulfur in barrels used for their whiskies.

While in Jerez for the launch of the Redbreast Lustau Edition, I had the opportunity to speak with Midleton Distillery Head blender Billy Leighton. Since I had a couple extra minutes, I asked him about the effect of sulfur in barrels used for their whiskies.As some background, the whisky writer Jim Murray, who seems to enjoy generating controversy to increase book sales, said that sulfured casks are ruining scotch whisky. I don’t know much about the topic, so I asked Leighton if it was an issue.

He said, “The use of sulfur to sterilize casks for shipping or storage is a common practice, but it has to be done carefully. In the year 2000 we stopped the cooperage from using sulfur candles when they’re shipping casks to us. There is always a little bit of a risk of infection or secondary fermentation when you do that. Also, we have only shipped barrels typically between Oct and Feb [the lower temperature months in order to avoid that fermentation/spoilage], though it’s expanding because of [increased sales] volume."

[Irish Distillers has a relationship with the cooperage Antonio Paez to build and prepare their sherry barrels, so they don't buy their casks on the open market. If they did they'd not be able to control/track this.]

[Irish Distillers has a relationship with the cooperage Antonio Paez to build and prepare their sherry barrels, so they don't buy their casks on the open market. If they did they'd not be able to control/track this.]He continued, "Historically you would have found a presence of sulfur from time to time. Now we have stopped that for 16 years. We don’t have the same problem certainly in our first fill casks. We could still see some sulfur raising its ugly head again in refill casks [casks purchased before 2000 that aged whisky and then were reused]. And one cask affected with it can ruin a vat. So even now every single sherry casks is personally screened by me."

That’s new info to me, and I thought I’d share.

-

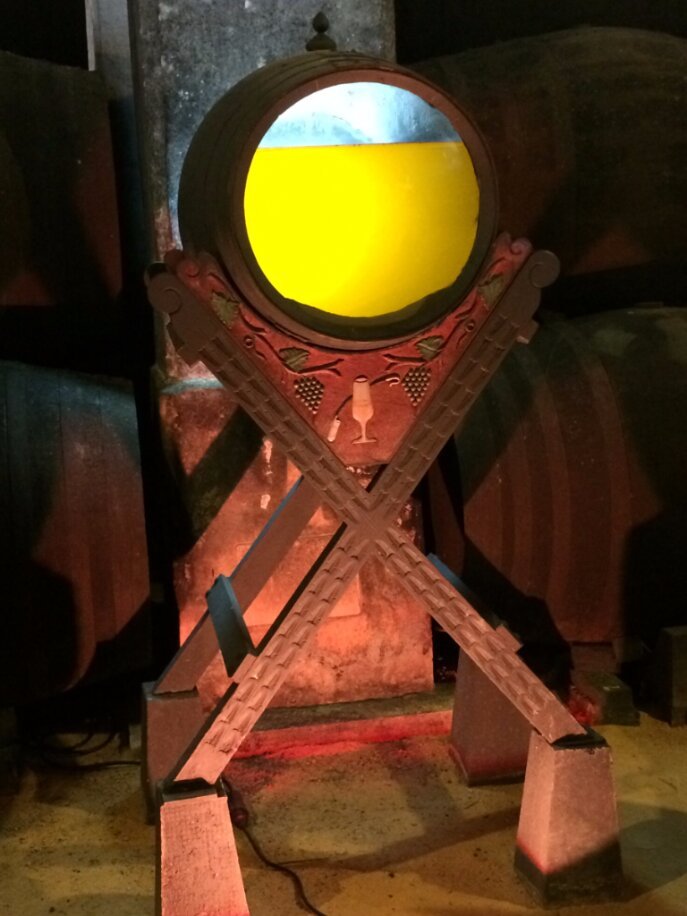

Why Sherry Cask Whiskies are Aged in Spanish Oak But Sherry is Aged in American Oak Casks

This is a simple point but one I didn’t know before. Often you’ll see that scotch and other whiskies are aged in Spanish oak barrels that previously held sherry. However, I’ve always been told the barrels in the sherry soleras are American oak. What gives?

This is a simple point but one I didn’t know before. Often you’ll see that scotch and other whiskies are aged in Spanish oak barrels that previously held sherry. However, I’ve always been told the barrels in the sherry soleras are American oak. What gives?Thanks to Billy Leighton, Head Blender at Midleton Distillery, I have an answer. He says that yes, the true barrels on the sherry soleras are American oak and as old as possible. They do not want wood influence in sherry so the barrels don’t lend any flavor.

Traditionally, sherry was shipped to the UK in barrels (rather than bottles), and for that they would use the much less expensive/lower quality (at least at the time; I can’t speak for that now) Spanish oak casks, rather than American oak ones.

After being emptied, those casks would have been the ones reused to age scotch and other whiskies.

The Redbreast Lustau Edition is aged in ex-bourbon American oak barrels and sherry conditioned Spanish oak casks.