This post is sponsored by Anchor Distilling, makers of three rye whiskeys in San Francisco, California.

Anchor Distilling makes three unique rye whiskies in a tiny corner of a big brewery in Potrero Hill in San Francisco. I visited, probably for my 6th time, to learn the story of how it all started and how the whiskies are made.

In the Beginning…

When you speak with start-up distillers, you realize that everyone wants to make whiskey, but whiskey takes time to age, it has the expense of barrels to age it in, and it requires space in which to age it. So most new distilleries launch vodka, gin, rum, and/or other unaged products first. That wasn't the case at Anchor Distilling, which launched an aged whiskey first and then gin later.

When you speak with start-up distillers, you realize that everyone wants to make whiskey, but whiskey takes time to age, it has the expense of barrels to age it in, and it requires space in which to age it. So most new distilleries launch vodka, gin, rum, and/or other unaged products first. That wasn't the case at Anchor Distilling, which launched an aged whiskey first and then gin later.

"We had a huge advantage in that we were all brewers, and the brewery was bankrolling all this. We didn’t have a time table to get a product out on the market. We could go until we had what we wanted," says Bruce Joseph, Head Distiller of the Anchor Distilling Company.

"We were lucky that we were able to spend a lot of time experimenting. There wasn’t a lot of information out there for small-scale distilling. It wasn’t what any bourbon distillers were doing." Joseph (interviewed in May 2014) had been a brewer long before Anchor's founder Fritz Maytag had the idea to launch a distillery.

"I was in my early 20s when I started working here. The brewery had just moved into this building. When I started working here there were 13 employees. I thought, 'I’ll do this for a little bit' and I started working here and there was a real sense that these were a group of people on a mission: making beer that the majority of people didn’t want to drink," Joseph says.

Making products (beer, then spirits) that won't be appreciated by most people ever, and not by hardly anybody for a while after they hit the market, seems to be both a point of pride and the business plan at Anchor.

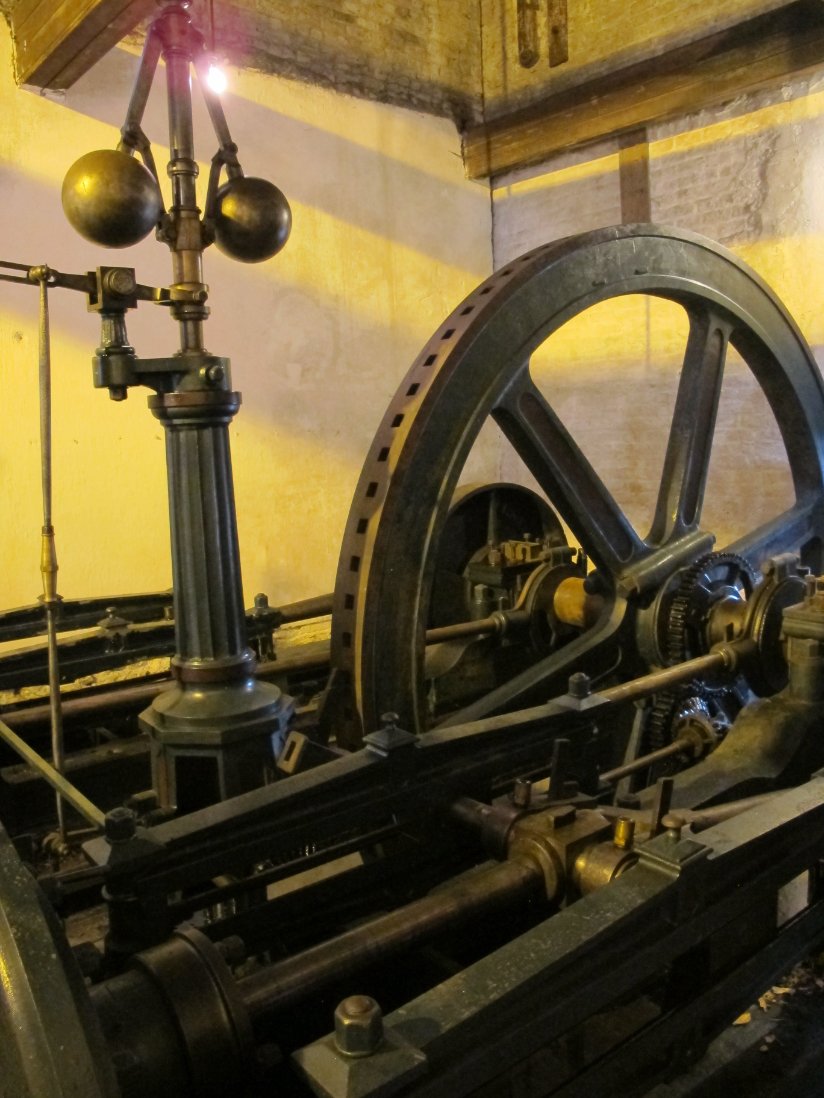

The still for second distillation of whisky and genever

In a 2012 interview of Anchor Brewing and Distilling founder Fritz Maytag conducted by Alan Kropf of Mutineer Magazine (and now the Director of Education at Anchor), Maytag said his success with the beer company led to an explosion of other creative beer makers, and then it became less exciting the more other people were making equally exciting beers.

"It got to where our competitors were coming out with all kinds of things including things that were kinda goofy. It got to where if you brewed a chocolate-blueberry stout people would say, 'Oh another one of those,' and I didn’t find that very rewarding."

[All quotes from Maytag come from the interview with Kropf, who gave me access to the recording.]

A Plenitude of Points of Differentiation

Bruce Joseph was there for the beginning of the experiments with distillation. He says, "Rye was perfect for Fritz because it was historical and it was hugely unpopular. No one gave a damn about rye whisky at the time."

Not only was the choice to make rye a bold one, the choice to make it in a pot still was radical. At the time, in 1993, there were no legal pot-distilled whiskies being made in America – it was all made in continuous column stills.

Furthermore, Maytag decided on a 100% malted rye whiskey to distill. He said, "The rules say 51% rye (to be legally called rye whiskey by US law) but the rye whiskeys don’t use malted rye- they just use rye- and probably some malted barley and some corn. Just as in Scotland they require that the single malt whiskeys be made with all barley malt mash, I thought, 'Why don’t we make rye whiskey but we’ll make it with malted rye?'"

He continued, "And we thought we could steal the phrase 'single-malt.' We stole it fair and square – the Scots forgot to trademark it!"

Malting is the process (required for all single-malt scotch whisky but with barley instead of rye) where the grains are allowed to germinate in wet conditions, then they're dried. This produces grain that is easily fermentable. (Most bourbons use a portion of malted barley in their recipes as this helps the other grains ferment, though today enzymes also help speed the process.)

The still for the first distillation of rye whiskey and genever

Joseph says, "Fritz had that idea that he wanted to do 100% rye. When we did early mashes we all just loved the flavor of the malted rye. It had a certain character and certain quality that was just real attractive. (Maytag described that taste as "a richer, warmer, friendlier flavor".) Once we started doing spirit distillation it just seemed that it was bursting with flavor."

Fake It 'Til You Make It

Yet another unique feature of the rye whiskeys made at Anchor is that the fermented mash goes into the still, not a wort. Or, in English: grains are fermented with water and yeast. After fermentation the whole thing goes into the pot still at Anchor.

This is unusual: In Scotland where they use pot stills for single-malts, they separate the solids from the fermented beer before distillation (and the liquid beer is called wort). This prevents those grain bits from sticking onto the side of the still during distillation and burning.

Additionally, rye is known for being very gummy and hard to distill because of that. Joseph says, "Rye is a sticky, viscous, mess – a brewer’s nightmare."

Luckily, their copper still came with a built-in agitator that can be turned on to keep the liquids in the pot moving so that nothing sticks and burns. Joseph says, "The very first time we did it, if my memory serves me well, we at first used the agitator when we were heating up the mash then turned it off during distillation. It caked onto the inside of the still, and once it’s cooked onto the side you don’t get heat transfer. We learned that in the first day or two."

And I bet somebody had a not-fun job of scraping out the inside of a small 600-liter still.

Age Is Just a Number, Except in California

The first single-malt rye whiskey from Anchor was aged barely over one year – 13 months. This was 1996, about six years before the whole white whiskey trend came to be.

Maytag said, "I thought that after 6-8 months our whiskey was just charming. It was kind of almost sweet. And since the (federal) law said that there were no rules about how long it had to be in the barrel – it just had to state the age (if under four years)- I said why don’t we bottle it at one year old?"

He continued, "Later we discovered we had broken the California law, which was a stupid mistake. But in California to be called whiskey, never mind rye whiskey, you have you to be in the barrel for at least 3 years, and some of the barrels have to have been charred. Which is absurd because there were no charred barrels until about 1840 or so."

Yes, another unique feature: one of the three single-malt rye whiskeys made at Anchor is aged in a hand-made, air-dried, toasted American oak barrel, while laws for bourbon specify charred oak and that's the standard. It was a combination of Maytag's wine expertise and dedication to make a historically valid whiskey that had led him to the toasted oak decision.

"We called it 18th Century-Style Whiskey because we couldn’t call it rye whiskey because it wasn’t aged in charred barrels. (But) that whiskey can’t be called whiskey at any age in California because there are no charred barrels. We still have a product that in California is labelled as a “spirit”; can’t call it whiskey, it’s crazy," he said.

This Is How It's Done

Anchor Distilling makes three rye whiskies.

Anchor Distilling makes three rye whiskies.

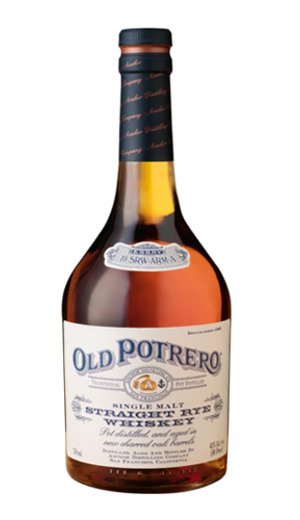

- Old Potrero Single-Malt Straight Rye Whiskey (sometimes called 19th Century whiskey)

- Old Potrero 18th Century Style Whiskey

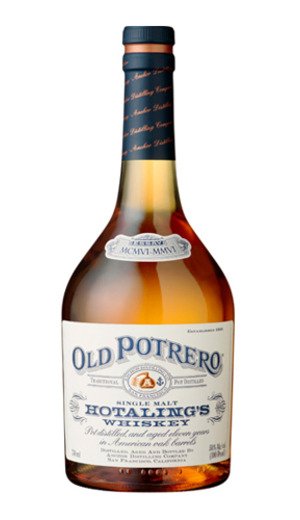

- Old Potrero Hotaling's Single-Malt Whiskey

They all start with the same distillate, made from fermented 100% malted rye mash. Then they all go into different barrels at the same proof, "a little below the legal limit of 125 proof," according to Joseph.

- The Old Potrero 18th Century Style Whiskey is aged in toasted barrels for 2.5 – 3 years, sometimes with a little bit of older whisky mixed in. Joseph says, "Toasted barrels work better for a younger whisky."

- The Old Potrero Single-Malt Straight Rye Whiskey is aged in new charred oak barrels for 4.5 – 5 years. Joseph says, "We prefer the whisky not to age too long."

- The Old Potrero Hotaling's Single-Malt Whiskey is aged in used whiskey barrels. These have always been ex-bourbon barrels, but recent releases will have been aged in used charred barrels that were used to age something else (forthcoming) at Anchor. Joseph says, "We kept tasting it but for the first 7 years we didn’t like it as much as the other whiskies. But finally we tried it after about 8.5 years after we hadn't in a while and we said 'We should have been putting more of this away!' The age of the release changes each year, as there isn't very much of it around.

The barrels were aged on-site in Potrero Hill for many years, but now they age in Western Sonoma County in a warehouse that keeps a San Francisco-like temperature year-round.

This post about the pioneering spirits created by Fritz Maytag and his team is sponsored by Anchor Distilling.

When you speak with start-up distillers, you realize that everyone wants to make whiskey, but whiskey takes time to age, it has the expense of barrels to age it in, and it requires space in which to age it. So most new distilleries launch vodka, gin, rum, and/or other unaged products first. That wasn't the case at Anchor Distilling, which launched an aged whiskey first and then gin later.

When you speak with start-up distillers, you realize that everyone wants to make whiskey, but whiskey takes time to age, it has the expense of barrels to age it in, and it requires space in which to age it. So most new distilleries launch vodka, gin, rum, and/or other unaged products first. That wasn't the case at Anchor Distilling, which launched an aged whiskey first and then gin later. Anchor Distilling makes three rye whiskies.

Anchor Distilling makes three rye whiskies.