In the summer of 2017 I visited Poland with Belvedere Vodka to see how the vodka is made and to learn about the then-forthcoming Single Estate Rye series of vodkas, in which the same rye was grown in two different parts of Poland and separate, unfiltered vodkas were made from each. We got super deep into the science of terroir.

In the summer of 2017 I visited Poland with Belvedere Vodka to see how the vodka is made and to learn about the then-forthcoming Single Estate Rye series of vodkas, in which the same rye was grown in two different parts of Poland and separate, unfiltered vodkas were made from each. We got super deep into the science of terroir.

Belvedere is made from rye, which is first distilled at one of seven regional farm distilleries, and then redistilled and bottled at a distillery named Polmos Zyrardow. ("polmos" = "distillery") From other trips to Poland I've learned regional distilling followed by central distilling is quite common- why truck all that grain around when you can condense it into high-proof spirit and just transport the liquid?

The Polmos Zyrardow distillery dates back to 1910, and they've been making Belvedere exclusively at the facility since 1993.

Polish Vodka

- If the bottle says it's Polish vodka, it can't have additives like sugar/glycerin etc.

- It must also be made from a grain (rye, wheat, triticale, oats or barley) or from potatoes, rather than other fermentable material like molasses.

- Though it must be additive-free (this is exclusive of flavored vodka of course), it can be aged.

- The first reference to vodka is from Poland in 1405.

- Here's a more official page of Polish vodka production rules and processes.

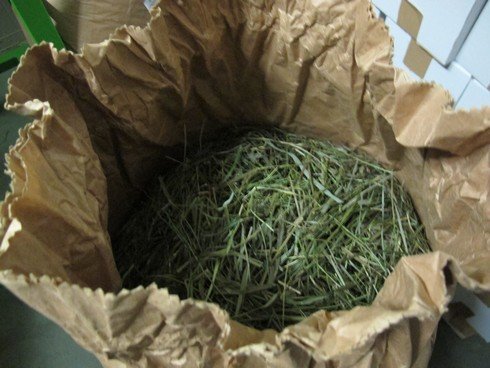

Belvedere is made from rye, which has been grown in Poland for over 1000 years. Rye can thrive in harsh conditions; both hot and cold. Belvedere Pure (the flagship original) is distilled from golden rye, a high starch strain good for making alcohol that dates to the 1800s. The Single Estate series is made from another variety called diamond rye.

On site at Polmos Zyrardow is a water treatment plant that processes water from their well water source a 3km from the distillery. Water is purified in four stages: oxidation to break down chemical compounds into smaller parts; mineral filtration to remove iron and manganese; a soft filter to remove calcium and magnesium, and a carbon filter to remove all taste and odor. For water that is used to dilute Belvedere to its final proof, this water is then further filtered with reverse osmosis.

High-proof spirit comes in from the 7 farm distilleries and is redistilled at Polmos Zyrardow. It comes in at around 90-92% ABV, then it is watered down to 44-45% ABV before going into the stills. There are three columns in this distillery:

- The first column is the purification column, which removed impurities at the lower boiling temperatures than alcohol.

- The second column is the main rectification column, which removes impurities at a higher boiling point than alcohol, and brings the spirit back up to 96.5-96.6% ABV.

- The third column is the methanol column, which removes methanol created during fermentation.

The distillery runs for two seasons per year (corresponding to rye harvests I imagine), 24 hours/day (because it's harder to start and stop column stills) for a total of 167 days per year.

All the flavored varieties of Belvedere are made in house in the "alembic area." There they have cognac stills. The various ingredients are macerated in vodka of different strengths, and left to sit from anywhere from 2 days to 2 weeks. The fleshy fruits might go into higher alcohol spirit and stay for longer than things like tea. They're then redistilled to make the concentrated flavors. They make each flavor separately, then blend them together for their combination products.

Belvedere Pure is charcoal filtered. (The single estate range is not.)

Finally the vodka is diluted and bottled at the distillery.

The Single Estate Rye Series, and the Science of Terroir

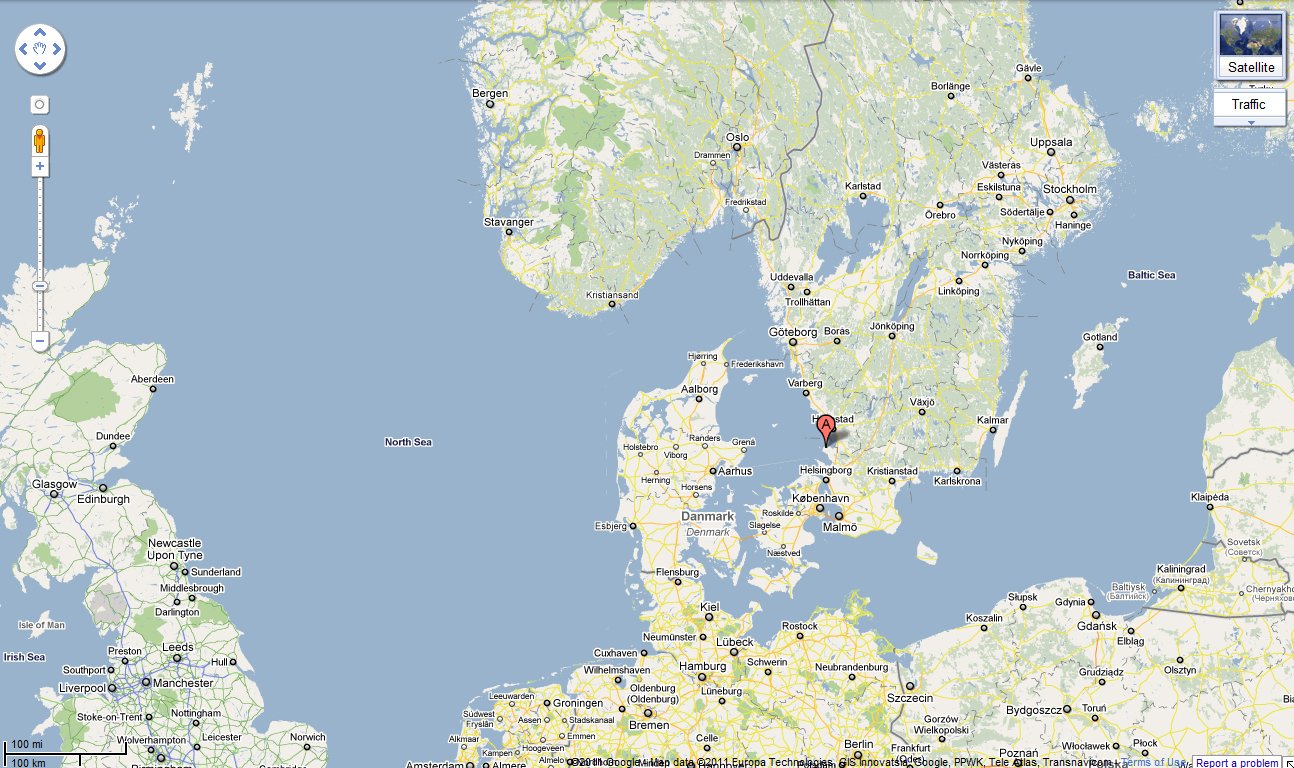

Our group then flew to the Lake District of Poland, to the Bartezek estate, where the rye for one of the two Single Estate Series vodkas is grown and first distilled. The flight passed over lots of green farmland, forests, and small farms before getting to the Lake District- from our flight path it looked like a series of lakes and streams between them.

The Lake District is made up of about 2000 lakes, and it's located far from industry and sources of pollution. The climate is of long snowy harsh winters and short summers.

We didn't visit the Smogory Forest estate, but the climate there is "the mildest in Poland." Belvedere Unfiltered vodka was the same product as the Smogory Forest single estate vodka is now- they changed the name to accent the difference between it and the other estate. This region has a longer growing season. It's not much of a farm region but a forestry one – half the land is forest.

The rye used for the Single Estate Series is a baker's rye called Dankowskie Diamond Rye- both farm distilleries grow the same rye. Typically bakers and distillers want different things from their grains: distillers want grains with high starch and low proteins (as I learned in Sweden), as they want to convert all those carbs to alcohol.

In fact, the golden rye used in Belvedere pure takes 1 square meter of rye to make 1 bottle of vodka. For this less efficient bread-making rye for the Single Estate series, it take 1.4 square meter's worth of rye.

Each of the Single Estate vodkas use the same yeast, though this yeast is different from that used to ferment Belvedere Pure.

We visited the local farm distillery where the Lake Bartezek-grown rye is first distilled. The grains have enzymes and water added to break it down into fermentable sugars, then it is fermented for 72 hours at 35C. After fermentation, the rye beer is from 7-11% ABV. After distillation in the single, 60-plate column, the spirit ranges from 88-93% ABV.

These two vodkas in the Single Estate series were sent out to laboratories for analysis: not just the final vodkas, but also the rye beer (the wort) from each. They were sent to analytic labs as well as reviewed by tasting panels. The results were that the differences between the two were much more pronounced before distillation, but chemical differences were found between them as well as tasting differences – so if you taste the vodkas differently, it's not just all in your head.

We went through the scientific and tasting panel analysis reports rather quickly, so hopefully the below doesn't have errors, but here were some results:

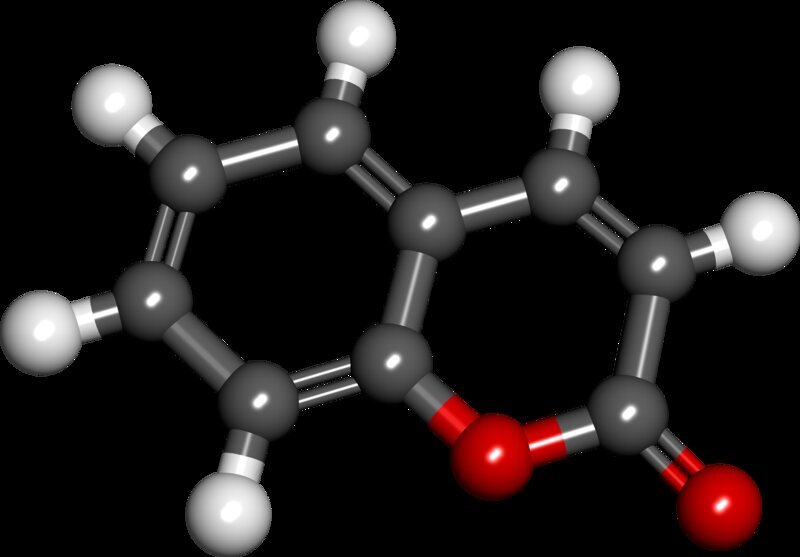

- The main flavor differences between the two single estate vodkas were due to Maillard reaction congeners (that produce toasty sweet notes) and lipid congeners (that produce fatty, waxy aroma compounds).

- The Lake Bartezek vodka had more impact by Maillard reaction congeners, with less lipid congener notes, and a higher amount of esters in raw spirit.

- The Smogory Forest vodka had more nitrogen containing hectacycles such as pyrazines (toast nutty, peanut, coffee, cooked notes), furfural (caramelized notes), 2-acetylfuran (almond honey sweet bready woody notes), and methyl 2-methyl 3-something notes (umami character).

The brand describes the tasting differences between the two vodkas as:

- Smogory Forest: "a bold and savory vodka with notes of salted caramel, white pepper and honey-kissed hints. It brings out the richer flavors of rye."

- Lake Bartezek: "a fresh and delicate vodka with hints of spearmint, toasted nuts and black pepper. It brings out the more nuanced characteristics of rye."

The production of the two vodkas wasn't 100% exactly the same: The way to do that would be to grow the rye in different places and distill it in the same place. For the single estate series, each vodka was distilled where it was grown. So beyond the local soil/weather conditions where the rye was grown (terroir), there were some other factors that could have influenced the final vodka's flavor. These include:

- The length of time the rye grew in each location was different, but I'd say this is an aspect of terroir rather than an exception.

- The water used for fermentation at each site. Water isn't just water, but includes different quantities of various minerals that can impact fermentation.

- The fermentation times were different at the two distilleries.

- One of the worts (rye beer) was filtered after fermentation but before distillation, and the other wasn't. I'm not sure what impact this would have in a column still specifically, but it makes sense that it would be some.

In any case, the brand admits that this product launch and overall experiment is merely "the beginning of the exploration of terroir" in vodka, according to former Head of Spirit Creation and Mixology Claire Smith-Warner.

It was a terrific trip for me – y'all know how much I love distillery visits – with about five times the science as usual.