In my latest story for SevenFifty Daily, I wrote about the return of cochineal coloring in spirits. As you probably know, Campari removed the cochineal from their formula around 2006. Now a lot of brands – some of them Campari substitutes, some not – are putting it back in.

Author: Camper English

-

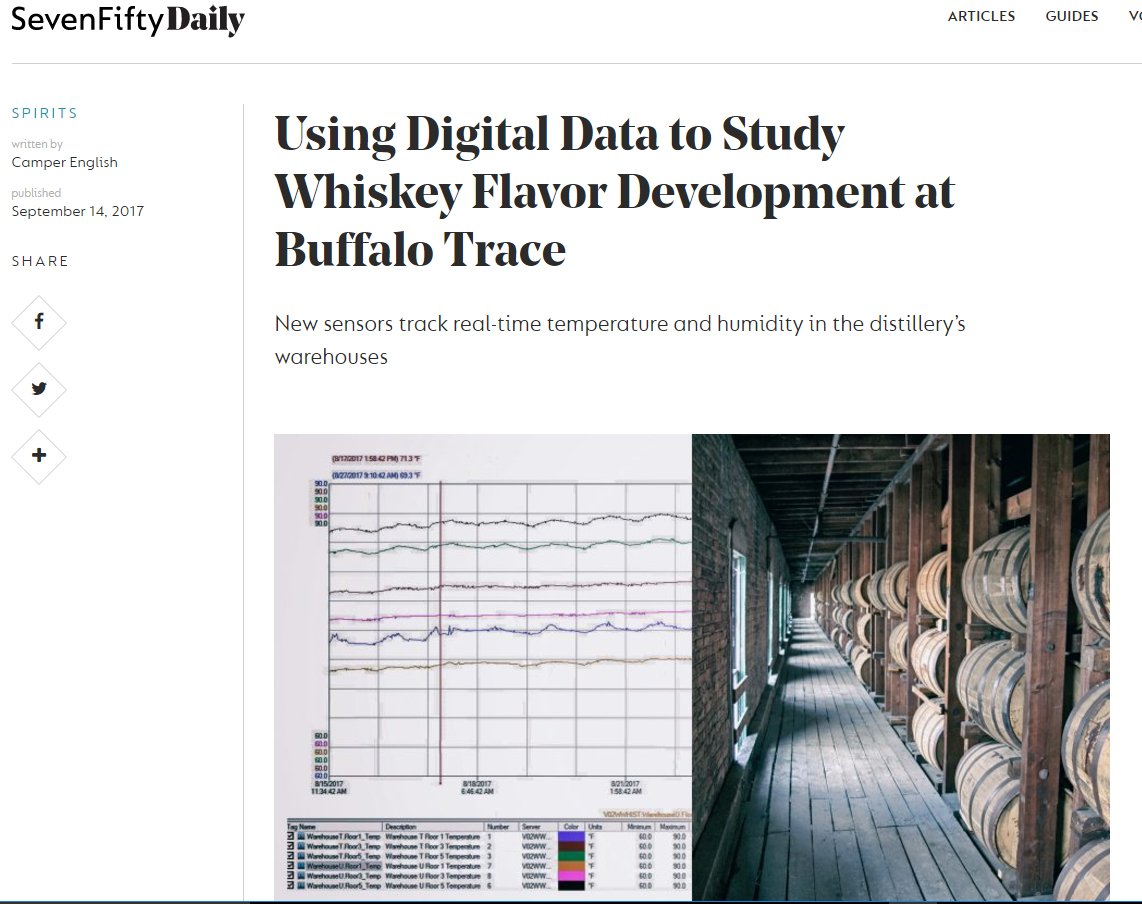

Sensors in the Whiskey Warehouse Sending Data in Real-Time

In my latest story for SevenFifty Daily, I wrote about new temperature and humidity sensors installed in warehouses at Buffalo Trace, and what those could mean for studying aging of spirits and adjusting future blends.

-

The ROI of TOTC

In my latest piece for SevenFifty Daily, I asked a bunch of people about the return on investment of Tales of the Cocktail: How they measure it and how they maximize it. I also interviewed Tales' founder Ann Tuennerman to get her advice on how to maximize the event as an attendee or small brand sponsor, and addressing the question, "Is Tales too big?"

In my latest piece for SevenFifty Daily, I asked a bunch of people about the return on investment of Tales of the Cocktail: How they measure it and how they maximize it. I also interviewed Tales' founder Ann Tuennerman to get her advice on how to maximize the event as an attendee or small brand sponsor, and addressing the question, "Is Tales too big?"I think there's some really good information and insight throughout the story, especially for people and brands experiencing some growing pains as Tales seems to grow ever larger.

Please check it out.

-

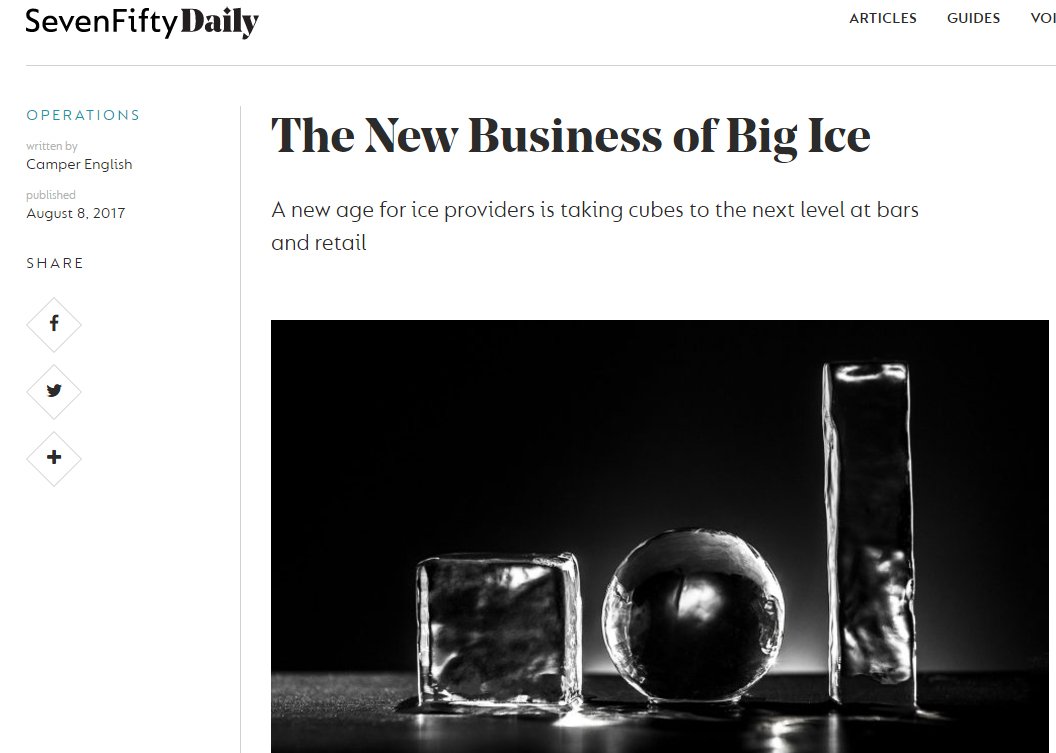

New Business Models for Large Format Cocktail Ice Providers

Large format cocktail ice providers have been around for a while, but now big cube/sphere/spear providers are branching out into new shapes, sizes, making machines, and pushing into retail.

In a story for SevenFifty Daily, based in part on my talk at Tales of the Cocktail, I wrote about what several companies are doing to bring more larger clear ice to more people.

-

Copyright, Trademark, and Patents for Bars, Brands, and Booze Recipes

My second story for the new industry-facing site Daily.SevenFifty.com is up!

My second story for the new industry-facing site Daily.SevenFifty.com is up! For this one, I covered a Tales of the Cocktail seminar called Intellectual Property Law Issues in Cocktail Land. It was lead by Trademark Attorney and Hemingway enthusiast Philip Greene, along with John Mason, a lawyer with Copyright Counselors, Steffin Oghene of Absolut Elyx, and Andrew Friedman of Liberty in Seattle.

It clarified the basic definitions of copyright, trademark, and patents, and there were tons of interesting examples – including the Curious Case of the Copper Pineapple!

The seminar description was:

If I make a Dark ‘n’ Stormy, do I have to use Gosling’s Black Seal Rum? What about the Painkiller, will Pusser’s Rum sue me if I use another brand? What about those iconic (and sometimes poorly made) New Orleans classics, the Sazerac, Hurricane and the Hand Grenade, will I get a cease and desist letter from anyone if I make them at my bar claiming trademark infringement? I keep hearing about Havana Club becoming available again from Cuba, but didn’t I also hear that Bacardi is planning to market their own Havana Club? What’s up with that? And speaking of Bacardi, didn’t they sue bars and restaurants back in the 1930s because those establishments failed to use Bacardi Rum in the drink? Is that true, and how did that turn out? Did I hear correctly that Peychaud's Bitters was the center of a trademark dispute way back in the 1890s, with the same family that founded Commander's Palace? And if I create a great drink and give it an awesome name, can I patent or copyright the recipe, and trademark the name? What if I get hired by a bar or restaurant to develop their beverage program, will they own the rights to the drinks that I invented or can I retain ownership rights in the recipes and names? Join the one veteran Tales presenter who is uniquely qualified to moderate this topic, Philip Greene, intellectual property and Internet attorney by day Trademark Counsel for the U.S. Marine Corps) and cocktail historian on the side (co-founder of the Museum of the American Cocktail and author of two cocktail books, To Have and Have Another: A Hemingway Cocktail Companion and The Manhattan: The Story of the First Modern Cocktail, in an in-depth, informative and fun seminar, and learn how to make (and enjoy samples of) some of these contentious classics while discussing this highly intellectual topic!

-

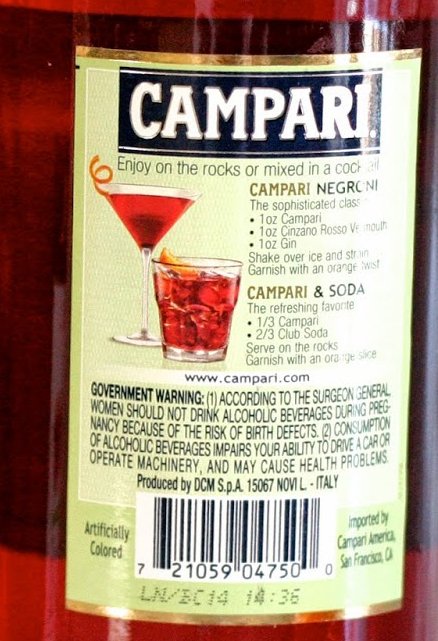

Campari is Made Differently Around the World: Cochineal, Coloring, ABV, & Eggs

I was researching a few different topics and stumbled upon an interesting observation: Not only is Campari sold at a wide-ranging variation of alcohol percentage in different countries, the coloring used to make its signature red is different depending on the country.

I was researching a few different topics and stumbled upon an interesting observation: Not only is Campari sold at a wide-ranging variation of alcohol percentage in different countries, the coloring used to make its signature red is different depending on the country. As many people know, Campari was traditionally colored with cochineal, a scale insect native to South America that grows on the prickly pear cactus. (Cochineal is still used in many products today, as it is a natural coloring and doesn't need to be labelled as the unsightly 'artificial coloring'.)

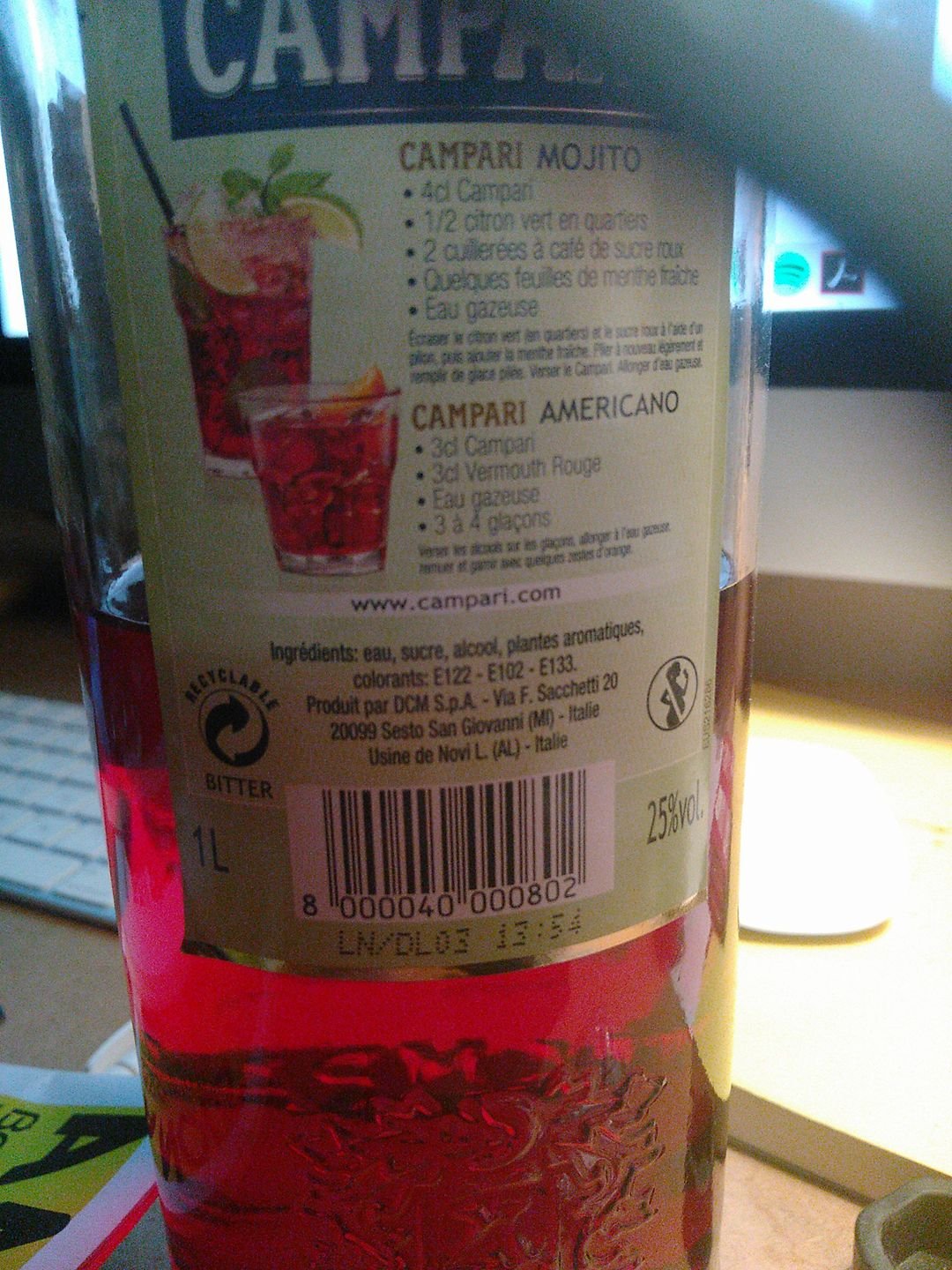

In 2006 cochineal was discontinued – but as it turns out, not everywhere. In the United States and it seems most countries, Campari now uses artificial coloring. Depending on which country one is located in, that coloring must be declared in different ways, so what is merely "artificially colored" in the US is labelled as three specific coloring agents in one country, and none at all in others.

But in at least one country, cochineal is still used.

In the United States, Campari is sold at 24% ABV and the coloring is listed as "artificially colored."

In France, the ABV is 25% and the colorings are listed as E122, E102, and E133.

Next door in Spain, no special colors are labelled, but it's also sold at 25% ABV.

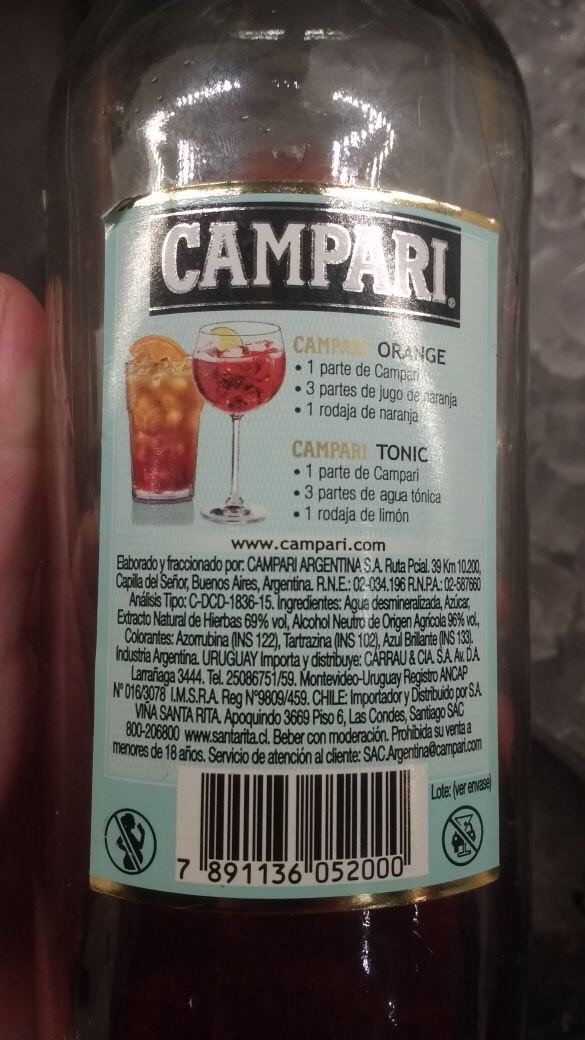

It appears it is the same in Argentina (with INS instead of E numbers), but the proof is 28.5%.

In Brazil it is the same, and labelled gluten-free.

In Toronto, it is sold at 25% and the color is merely misspelled (kidding!) as "colour."

In Australia, it is sold at 25% with no special color labelling.

In Malaysia it is the same – 25%, no color labelling.

In Japan, it appears to be sold at 25%. Anyone ready Japanese and can tell me if it says anything about coloring or eggs?

(One reader responds: "Red #102, Yellow #5, Blue #1. Don't see any mention of eggs.")

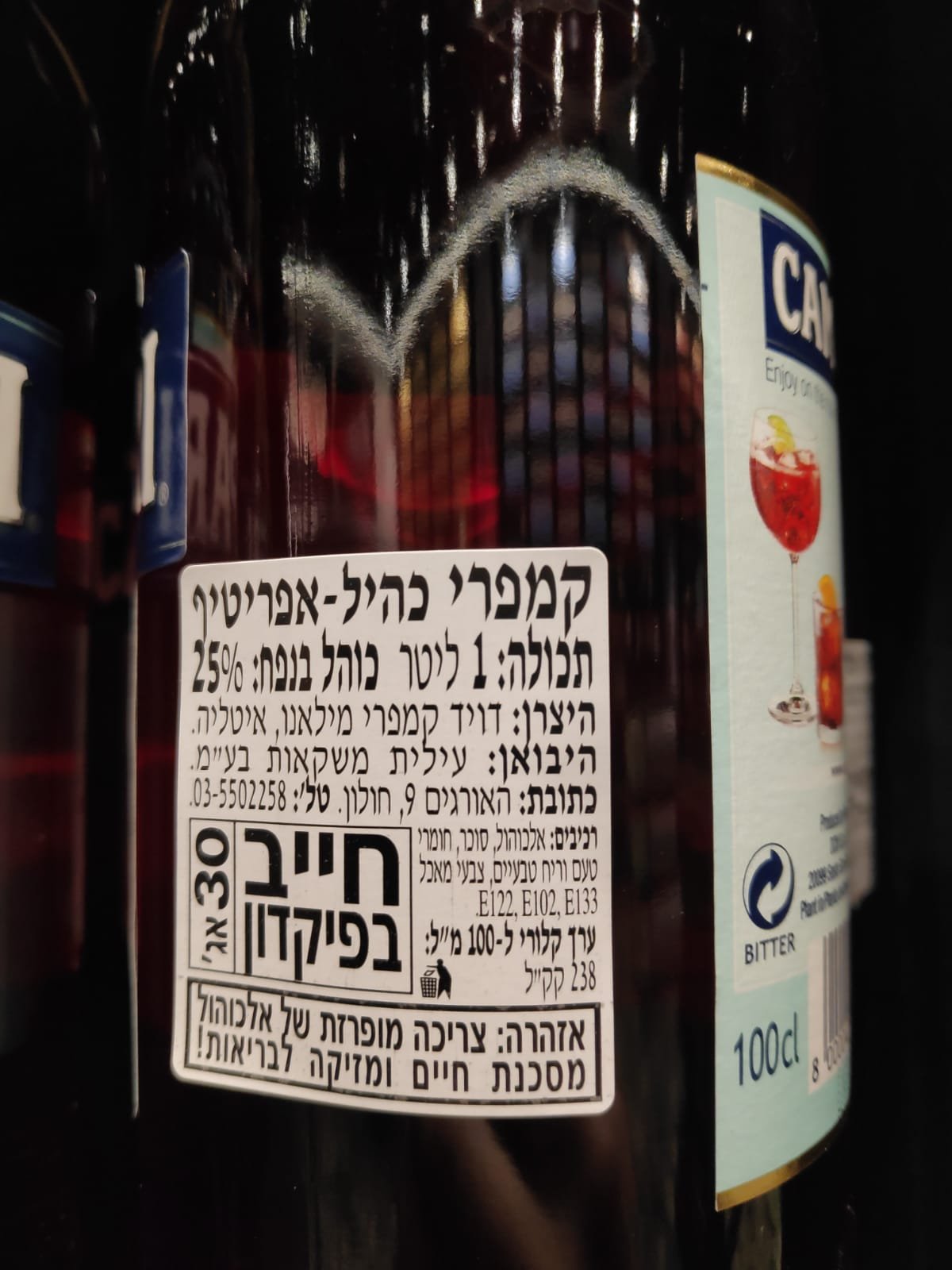

In Israel, it's sold at 25% ABV with E122, E102, and E133 listed as colorants.

In Iceland, it's sold at 21% ABV with no special color labelling.

Now here's where it gets really interesting.

I was wondering if the Swedish government website was merely out of date as it lists the coloring as E120 – that's cochineal(!), but a friend just picked up a bottle recently and cochineal is still in Campari in Sweden. Additionally, it is sold at 21% ABV.

Update: A twitterer sent me a pic of bottles from Mexico – they also have cochineal! See the E120:

And even more interesting is this bottle of Campari from Jamaica. Hold onto your butts:

- "Blended and bottled in Jamaica… by J Wray & Nephew" [Campari now owns JW&N]

- 28.5% ABV

- "Contains Egg"

CONTAINS EGG. Folks, that is some interesting news right there. Typically when eggs are used in wine, beer, and spirits (that aren't egg-based liqueurs), the eggs have been used in the fining process that helps filter the products to clarity. I think it's fair to assume this is how eggs are used in Campari.

My guess would be that because Jamaica has a Rastafarian community, many of which are vegans, products fined with eggs are required to be labelled.

What this means though, is that even though they took out the cochineal insect coloring (except in Sweden and Mexico apparently), Campari, at least in Jamaica, is still not vegan.

The question remains what it is in the rest of the world – I would bet that Campari is still not vegan.

Keep in mind that much cane sugar is whitened using bone charcoal, so any liqueur or sweetened alcohol has an okay chance of being non-vegan.

Thank you to my Facebook and Twitter friends from around the world who shared their bottle images. If you live in another country not mentioned here, please send me your bottle image to add to this discussion. Thanks!

-

The Impact of Phylloxera on Absinthe

I'm giving a talk at Tales of the Cocktail on "Bugs and Booze," and in reading up on the vine-killing aphid phylloxera, I came across a point of history I didn't understand.

I'm giving a talk at Tales of the Cocktail on "Bugs and Booze," and in reading up on the vine-killing aphid phylloxera, I came across a point of history I didn't understand.Phylloxera devastated the French (and eventually the world's) wine industry from the 1860s to around 1900. Most absinthe was made with a base of brandy- distilled wine- so it too should have been affected by phylloxera and been less available.

But if that was the case, then why did absinthe sales supposedly soar during phylloxera, and why did the wine industry feel the need to launch a negative PR campaign against drinking absinthe when it recovered? (This PR campaign was successful in getting absinthe banned in France and other countries for nearly 100 years.)

So I posted a question to my smart friends on Facebook:

Absinthe nerds: We always hear that post-phylloxera the recovering wine industry did a negative PR campaign on absinthe so that wine could resume its place on the throne. But wasn't most absinthe originally made with a wine/brandy base? When did it switch to a grain base (if it really did) – during or previous to phylloxera? Does anyone have historical data on this?

Well, many, many comments later, I have some ideas about the impact on absinthe, thanks to experts including Anna Louise Marquis, Joshua Lucas, Brandon Cummins, Gwydion Stone, Jack Crispin Cane, Fernando Castellon, Stephen Gould, Francois Monti, Ted Breaux, Heather Greene, Brian Robinson, Alan Moss, and others!

I'll break down my understanding of it. You'll note that I'm not citing any sources here so it's up to you to fact-check, but this is what I got from listening to absinthe history experts:

The Base Spirit of Absinthe Changed Due to Phylloxera

Absinthe can be made with any base spirit. Legal regulations were proposed in France that certain quality marques of absinthe (such as "Absinthe Superieure") need to contain grape distillate as the base, but these were never put into law as far as I know. (One source said the wine lobby actually worked to block any quality markers for absinthe.)

Not all absinthes were made with a grape-based distillate (but marc/grape was considered the best); and absinthe in general had a problem with low-quality (or even poisonous) brands with additives masquerading as the good stuff.

Sugar beet spirit became a predominant base spirit not only in absinthe, but in most French liqueurs. This is due only in part to the absence of grape spirit during phylloxera: Napoleon had launched a massive campaign to plant sugar beets in France to be more self-reliant. From a post I wrote in my project studying sugar: "Napoleon, due to the economic and real war with England, bet big on sugar beets. In 1811 he supported vast increase in sugar beet production. Within 2 years they built 334 factories and produced 35,000 tons of sugar."

Additionally, column distillation came along in the 1830s, which made it easier to get a high-proof, nearly-neutral spirit from most any base material. So in addition to sugar beets, things like potatoes and grain were used as a base for absinthe.

So there were many reasons that the base of most absinthes changed to sugar beet or grain during phylloxera. Pernod Absinthe's quality selling point was that it never changed its base.

Sales of Absinthe Soared in the Age of Phylloxera

True, from pretty much all accounts. Sales of absinthe were increasing before phylloxera, but absinthe's low price and wide availability during the crisis further helped sales. Then after absinthe was banned, sales obviously dropped a bit. So the 30 year period of phylloxera in France coincided with the glory days of absinthe. This is the heart of the Belle Epoque 1871-1914.

Absinthe was Banned Due to the Wine Industry Running a Negative PR Campaign

Anti-absinthe propaganda began before phylloxera did, promoted by a Temperance movement. Much like in the US, distilled spirits were considered the problem with drinking, while beer and wine were considered healthy. (Francois Monti says that beer/wine were considered 'natural' while spirits were 'artificial'.) So the anti-absinthe movement was already in motion pre-phylloxera.

But certainly the low-quality (and low-priced) absinthes on the market, which surely became of even lower quality during phylloxera when there was less wine to go around, were a problem, and gave anyone who was opposed to absinthe a target. As some people commented, now even the lower classes were drinking absinthe, for shame!

When the wine industry recovered fully or in part, they wanted all their sales back so they engaged in/funded negative PR campaigns about how dangerous absinthe was. These campaigns helped get absinthe banned after 1900 in many parts of the world.

Well, that's a short version of a very long and interesting discussion. I hope I've done it justice.