I've been writing for Fine Cooking magazine's website for several months now, and realized they don't have a recipe for the Caipirinha online. Shameful. So in my latest post I wrote about the drink, the base spirit cachaca, and some variations. Check it out.

I've been writing for Fine Cooking magazine's website for several months now, and realized they don't have a recipe for the Caipirinha online. Shameful. So in my latest post I wrote about the drink, the base spirit cachaca, and some variations. Check it out.

Author: Camper English

-

The Missing Caipirinha

-

Casa Noble Distillery Visit

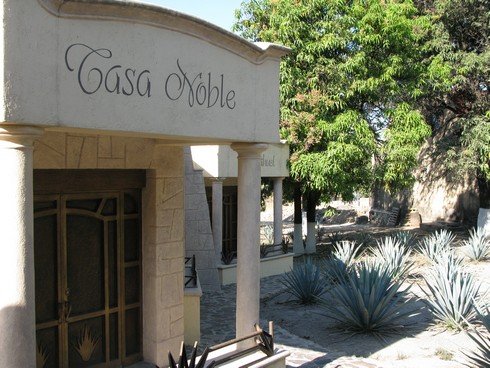

Way back in February I took a quick trip to Mexico to visit the distillery La Cofradia, where they make Casa Noble tequila. They make other brands there too, but I was there as the guest of their flagship brand Casa Noble.

A Beautiful Distillery

La Cofradia is located about a mile outside of the town of Tequila in the Lowlands of Mexico about 45 minutes outside Guadalajara. In Mexico a few distilleries cultivate a garden-like environment but here they take it to another level. There is a central courtyard with trees, a duck pond, a little cafe, and a set of four cottages where visitors like me can stay.

Casa Noble Tequila Production

Casa Noble is a certified organic 100% agave tequila. In order to be organicaly certified you need to prove that the land has been organically farmed and not had chemicals used on it for a certain number of years. Casa Noble avoided that problem by purchasing virgin land in Nayarit and planting fresh agave there. Nayarit is one of the five states where it is legal to grow agave, though nearly all of it comes from the state of Jalisco where the distillery is located.

Thus Casa Noble uses estate-grown agave. This is a growing trend in the tequila industry; producers owning or renting the agave fields so they can control the both the care and harvest of it, but also the price, avoiding the dramatic gluts and shortages of agave in the industry as a result of its long, 6-11 year growing cycle.

The fields in Nayarit are at an elevation of about 4000 feet, higher than some of the Highlands. Yet the agaves I saw at the distillery were much smaller than Highland agave I've seen. Those are often 200 pounds compared with the 110 pound or so average at Casa Noble (and thus only had to be split in half before baking; some Highland producers split theirs into quarters). They purposefully chose an isolated location for their fields, because they are organic: they wouldn't want airborne agave diseases to spread to their fields.

After harvest, the agave pinas are brought to the distillery where they'll be baked, shredded, fermented, and distilled. Baking converts the complex sugars in the agave into simpler, fermentable sugars.

(Closeup of piece of agave. You can see the fibers. The sugars are stored between these fibers which is why agave is shredded after baking to release them.)Baking and Shredding

La Cofradia has 5 hornos (ovens), 3 large 40-ton ones and 2 smaller 20-ton ones. The agave is steam baked for 36-38 hours. Then it cools before the next step. They hasten the cooling process by using large fans blowing through the two sides of the oven.

When agave is cooking with steam, the first water than runs off the bottom is called "bitter honey" and it is discarded. The next mass of water is called the "oven honey" and this is collected. We sampled this water- its sweet, watery, and has a vinegar note to it. (David Yan, Marketing Director there, says he's used a refined version of this as a vinegrette on salads.)

(Baked agave.)After baking the agave is shredded to expose the fermentable sugars that can be washed out and fermented. At La Cofradia they have a unique system: First the baked agave pinas are put through a sort of wood chipper (not a roller mill) with water. This water is collected and they call it the "fat extraction."

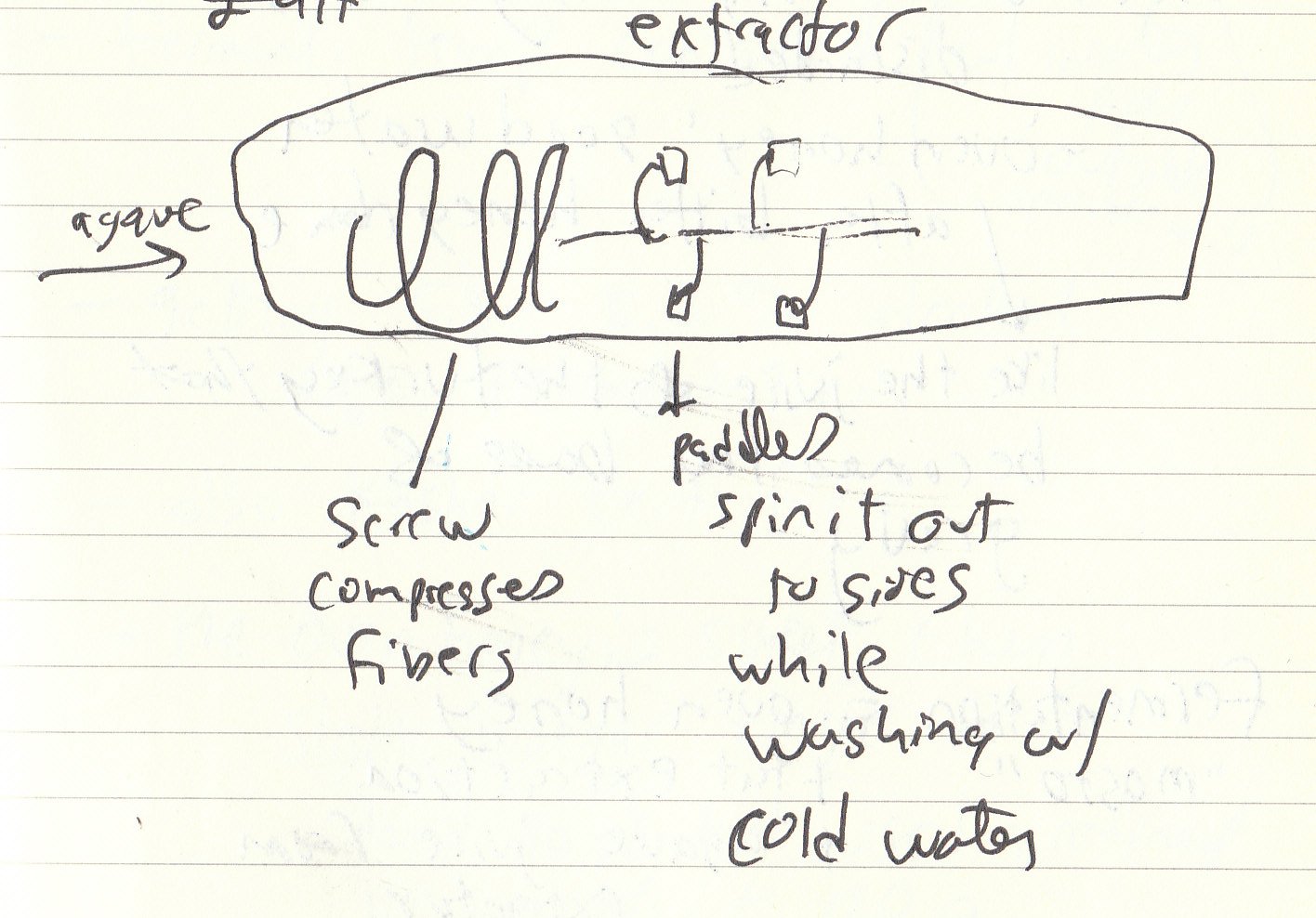

Next the chipped agave goes into a two "extractors" that are shaped like horizontal metal tubes. The first part of the extractor is like a corkscrew that compresses the fibers in the agave. Then it passes through to a set of paddles on a central axis that spins the agave fibers outward and washes them with water. Apparently this helps separate the fibers without neccesarily shredding them.

(Diagram of extractor from my notes.)Fermenting and Distilling

Now, onto fermentation. They ferment the combination of the oven honey, fat extraction, and agave juice from the extractors. Yeast is added that feeds on the fermentable sugars and converts it into alcohol plus CO2. While filling the fermentation vats, they bubble air into the tank, which they say makes the yeast reproduce more. This increases their alcohol conversion by an extra 1-2%.

After fermentation (3-5 days, depending on the time of year), the yeast has died and the juice is called "mosto muerto." Now it's time to concentrate the alcohol through distillation.

At La Cofradia they have large and small stills for the first and second/third distillations. The first, large stillas are called "destroyers" and their job is to get rid of most of the heads and tails.The resultant spirit is 22% alcohol.

(Destroyer stills closer, smaller stills further away.)The smaller stills are used for both a second and third distillation that refine the spirit. Though the first distillation cuts most of the heads and tails, there are smaller cuts on the second and third distillations. Both bring the alcohol to 55% ABV. (For most of the other brands that are produced at La Cofradia, they distill only twice. As this is the flagship brand they refine it more.)

After distillation (or, in the case of the aged tequilas, after aging) the tequila is filtered through micro-cellulose fibers and diluted to proof. The blanco (only?) is oxygenated before bottling for 8-12 hours.

Aging and Tasting

The barrels for aging Casa Noble come from the Taransaud cooperage in France. They're new French oak with a light #1 char, and nobody else in Mexico uses these barrels.The tequila goes into the casks at 55% ABV from the still (not watered down before barreling).

Interestingly, the tequila destined to be anejo (minimum 1 year aging) goes into new casks. The reposado (2 months to 1 year aging) goes into refilled caks. (More often, brands will use newer casks for reposado tequilas and older ones for anejo so that the wood affects the spirit more in a shorter time for the reposado.) They refill these casks for reposado 7-8 times.

Cristal/Blanco: This tastes of nickel and minerals, white and red pepper, and "agave sticks" according to my tasting notes.

Reposado: The reposado is aged for 364 days, the maximum amount before it would be in the anejo category. Reposado is aged in all 228-liter barrels. My tasting notes were: Boo-berry, strawberry cream popsicle, and white flowers.

Anejo: Here's where Casa Noble separates itself from the pack yet again. Though all barrels are new French oak from Taransaud, they actually use three different sizes of barrels: 114 liter, 228 liter (about the size of bourbon barrels), and 350 liter barrels. These are blended together to create the anejo.

The anejo is aged for 2 years. (Anejo is aged a minimum of one year. Extra-anejo starts at three years.) You can definitely taste all three of the below flavor profiles in the anejo.

We were given the opportunity to taste tequila aged in each of the three sizes of barrels, each of them for a little under two years.

114 liter: bitter wood, used peanut oil

228 liter: fruit, dusty Boo-Berry, most similar to the reposado

350 liter: floral, strawberry juice, lightNow, besides Casa Noble, I can only think of one other set of brands that ages their spirit in similar casks of different sizes: Jim Beam. Laphroaig and Ardmore both do "quarter cask" programs.

So, Wow.

This is a distillery that uses traditional methods in many ways (stone ovens, gentle agave processing) yet has built their system from the ground up (new agave fields, agave processing methods, distillation, aging). And it's all done in a lovely setting to which I'd love to return someday.

-

Angostura Rums Distillery Visit

In my last post I talked about the history and production of Angostura Bitters. In this one I'll talk about the history and production of Angostura Rums. I visited the distillery on Trinidad in March 2011.

History of Angostura Rums

The House of Angostura was in the bitters business since 1824, but didn't enter the rum business until after their move to the island of Trinidad in 1875. At first they were dealing with bulk rums rather than distilling their own, but in 1945 they purchased their own distillery. It wasn't until the 1960s that the profits from rum outsold those of bitters. In 1973 they purchased the Fernandes Distillery located next door and incorporated those brands (including Vat19) into their production.

According to the film we watched at the distillery, in 1991 they had a production capacity of 22 million liters of alcohol per year. According to their website, it's now 50 million liters. Wow! The distillery takes up 20 acres of land. They make both their own brands, rum for other people, and sell bulk rum. More on the other brands later.

Production of Angostura Rums

Currently all the products are made on enormous column stills. They say they've been experimenting with some pot still stuff, but they're not making anything yet.

No sugar has been produced on the island since 2003, so all the molasses to make these rums is purchased on the open market. (10Cane, which is also made on Trinidad but I don't believe at this distillery, uses some fresh local sugar cane juice in their rum blend.) We tastes molasses off the grate where it is poured into the system- it reminded me of old-style black licorice.

(Grate through which molasses is poured.)For different rum products made at the distillery they use different strains of yeast. Their barrels are ex-bourbon barrels. These are reused to age rum three times before they're discarded or recycled. We weren't allowed to enter the aging warehouse as they said it's a bonded property. From outside, it didn't look nearly big enough to age all the rum produced here, but they said it's their only aging warehouse it turns out they have five other aging warehouses also.

For further reading, I suggest Ed Hamilton's write up on MinistryOfRum.com.

The Line of Rums

After the distillery tour we did a tasting of some of the rums with Master Distiller Jean Georges. Oh, by the way, the line of Angostura rums is finally coming to the US soon, and they are tasty.

The 3-year reminded me (keep in mind my tasting notes aren't supposed to make sense to anyone but me) of the insides under-ripe banana peels, with a soft creaminess that wasn't too vanilla-y.

The 5-year, interestingly, is actually filtered to remove some of its color. It has the caramel-vanilla notes you'd expect from a rum of this age, but with a nice fuzzy texture. I was also picking up a lot of notes of liquid limestone. The finish had some mint/oregano spice to it and it was just a touch tannic.

The 7-year rum is actually the 5-year rum which is blended and then put back into casks to marry for 2 years. The nose is all warm caramel apple and cheesecake pie crust on this one, with a spicier mouth with notes of peppermint. It's also oily in texture and slightly ashy.

One thing Jean Georges said about all of their rums is that they have a short finish. "None of our spirits overstay their welcome. They do their thing and move on, leaving you to want another sip."

I am not sure if their "single barrel" is coming to the US or not, but I enjoyed drinking that during my visit. Most of the time I drank that or the 7-year-old. When I wanted a mixer, I'd mix it with their soft drink Lemon Lime & Bitters, locally known as LLB. (Note to Angostura: you should consider bringing this to the US also in select markets.)

Angostura also produces Zaya rum, The Kraken spiced rum (according to MinistryOfRum), Vat 19, and White Oak (which is very popular in Trinidad).

-

The History and Production of Angostura Bitters

In March I visited the Angostura distillery in Port of Spain, Trinidad. They make not only Angostura Bitters here but also the line of Angostura rums and rums for several other brands. In this post, I'll focus on the bitters.

The History of Angostura Bitters

Angostura Bitters were created in 1824 by Dr. Johann Siegert. They were originally called "Dr. Siegert's Aromatic Bitters" and later renamed Angostura Bitters. (The folks from The Bitter Truth Bitters have some interesting information about a lawsuit over the name "Angostura" between these bitters and Abbott's Bitters.)

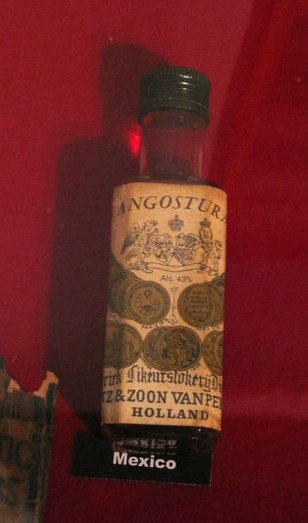

(One of the other Angostura Bitters bottles from around the world on display at the museum.)The bitters were created for tropical stomach ailments in Venezuela, as Dr. Siegert was the Surgeon General of Simon Bolivar's army. In fact the town of Angostura is now called Ciudad Bolivar. The bitters were first exported to England in 1830.

According to this good history on Angostura's website, Siegert's son exhibited the bitters in England in 1862 where they were mixed with gin. Thus the Pink Gin was born.

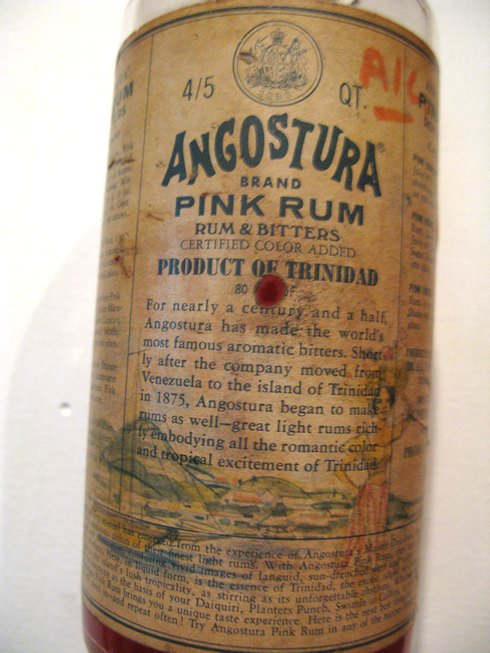

(Angostura used to produce Pink Rum – rum laced with Angostura Bitters.)After Dr. Siegert died in 1870, his sons relocated the business from the politically unstable Venezuela to Trinidad in 1875. The company was renamed Angostura Bitters in 1904. Sometime shortly after this, the son in charge of Angostura lost all of his money in bad business deals and Angostura was taken by his creditors.

Why is the Angostura Bitters Label Too Big for the Bottle?

For a competition of some sort, one brother designed the bottle and another brother designed the label. By the time they figured out they should have consulted each other on the size of each, it was too late to change. On the advice of a judge in the contest, they kept it as their signature. Here, our tour guide does a better job of explaining it in this 1-minute video.

How Are Angostura Bitters Produced?

The secret ingredients for the bitters are shipped from wherever they come from to England. There the ingredients are put into coded bags and shipped to Trinidad. I believe they said they have a long-standing arrangement with customs that the bags are not inspected when they arrive in Trinidad to maintain their secret.

At the distillery, there are five people known as "manufacturers" who prepare the ingredients. They weigh out the relative quantities of each in a room known as the Sanctuary. The ingredients are then dropped into a crusher that crushes them all together as they fall into the room below – the Bitters Room.

At the base of the crusher are carts that hold the ingredients. We weren't allowed to take pictures in the room due to the high-proof alcohol vapors (but later did of the bartenders there), but we did get to peak into the crushed herbs. I remember seeing largish chunks of something that looked like gum arabic, and a lot of rice-sized grey grains about the size of lavender seeds, though I doubt they were because there was a lot of them. (There you go: gum arabic and lavender- make your own Angostura at home 🙂 )

The crushed herbs then go into a "percolator" tank with 97% alcohol to extract their flavor. After this infusion is done, the liquid is then transferred to another tank where brown sugar and caramel color are added. Then the liquid is transferred again and distilled water is added to bring them down to the 44.7% alcohol level for bottling.

This is all done in a relatively small room with a bunch of tanks in it. It's impressive that the world's supply of Angostura Bitters is made here.

Later that day, they did publicity shots with the bartenders in the Bitters Room. They let the professional photographers take photos and let me take them without flash. As you can see the bitters tanks have the bottle labels on them. Except in this case, they actually fit.

-

For the Love of Orgeat

In my latest post for FineCooking.com I talk a little bit about orgeat as a segue into posting the recipe for Dominic Venegas' Mi Ruca cocktail that helped him win the SF regional 42Below vodka cocktail world cup.

(Photos courtesy of 42Below Vodka.)Most of what I know about orgeat comes from the research for a huge Mai Tai story I wrote for Mixology Magazine in Germany. And much of that information comes from Jennifer Colliau of Small Hand Foods, whose orgeat is so labor-intensive she only sells it to select clients, and Blair Reynolds, whose Trader Tiki orgeat now comes in regular almond and hazelnut versions.

Venegas' Mi Ruca cocktail is simple to make at home as long as you have the delicious 42Below Manuka Honey vodka; and you can use commercial orgeat and skip the bee pollen if you don't have any around.

The recipe for the Mi Ruca is on Fine Cooking here.

(Photos courtesy of 42Below Vodka.)I am out of Manuka Honey so I made a rum version of this drink- dark rum, pineapple, lemon, and orgeat. It tasted like a simple rum punch and was good on its own though crying for some champagne to give it fizz.

So shopping list: champagne, manuka honey vodka, bee pollen. At least I've got orgeat in the house.

-

Pickle Back in Los Angeles Times Magazine

I wrote up a short ditty on the Pickle Back (A shot of whiskey- usually Jameson- with a pickle juice chaser) for the Los Angeles Times Magazine's March issue.

Read it here.

-

Irish Coffee: It’s All in the Cream

In Ireland a few weeks ago, I had Irish Coffee three times in as many days. Irish Coffee was invented in Ireland and is credited to a bar at the Shannon airport. Then it was recreated in San Francisco at the Buena Vista. Its popularity in the US helped it travel back to Ireland where became popular around the country.

At the Chapter One restaurant in Dublin, they have the most elaborate preparation of the Irish Coffee in town. They add Jameson Irish Whiskey and 2 tablespoons brown sugar to a pan and caramelize it for 10 minutes and grate fresh nutmeg on top. They add half the amount of coffee, then light the pan on fire for just a second and blow it out. They add the other half the coffee then pour it into the glass.

Then they add the cream on top. Unlike the other Irish Coffees I've had, the cream was fairly warm as opposed to refrigerator-cold. Most of the fuss of an Irish Coffee seems to be about the cream. I address this in last week's post on FineCooking.com.It turns out different countries have conflicting definitions for cream, and even in the US you have to know the difference between "whipped" and "whipping" cream to get it right.

The good news is, once you buy the right cream you don't have to whip it very much yourself- just don't stir the coffee first, and pour it over the back of a spoon. More info is in the post here.

-

What’s the Difference Between Orange Curacao and Triple Sec?

There are no legal differences between triple sec and Curacao, only a few practical and many historical differences. In summary:

There are no legal differences between triple sec and Curacao, only a few practical and many historical differences. In summary: - Both triple sec and Curacao are orange-flavored liqueurs, and today’s triple secs are typically clear, while curacao is either clear or sold in a variety of colors, including blue.

- Curacao liqueur is not required to come from the island of Curacao nor use Curacao-grown oranges, and according to US law, both triple sec and curacao are simply defined as “orange flavored liqueur/cordial.”

- Some orange liqueurs including Grand Marnier use an aged brandy base, while most use a neutral spirit base.

In short, today there are no hard and fast differences between curacao and triple sec (other than curacao is sometimes colored), and bartenders should use what is best for a particular drink. But the history of how orange liqueur came to be known by these different names is interesting.

From the Caribbean to the Netherlands

"Curacao" liqueur refers to a liqueur with flavoring from oranges that grow on the island of Curacao, off the coast of Venezuela. These oranges are known as bitter oranges or Laraha oranges, with the botanical name Citrus aurantium var. curassuviensis.

These are a variety of sweet Seville oranges that changed in the arid island climate and are reputed to taste awful on their own, but the sun-dried peels of them are prized in making liqueur compared with traditional sweet oranges. Today, bitter oranges are still used in many liqueurs and some gins, though these are most often sourced from other regions including Haiti and Spain.

However the Senior & Co. company, based on Curacao since 1896, still produces curacao (in a variety of colors) made on the island with the island’s oranges. It claims to be the only brand that uses the island’s oranges.

The island of Curacao has been a Dutch island since the 1600s, and was a center of trading and commerce for The Netherlands. The dried peels of the island’s oranges made their way back to Holland where they were infused, distilled, and sweetened. The Dutch Bols company, which dates back to 1575, states that their first liqueurs were cumin, cardamom, and orange, though they don’t specify that the oranges in the first liqueur came from Curacao just yet.

The base spirit for orange liqueurs changed many times over the years. According to Bols historian Ton Vermeulen, the earliest records of distillation in the Netherlands dating to the 1300s detail distilling grapes. The northerly climate isn’t conducive to grape-growing however, and by the end of the 16th century many distillers used distilled molasses (sugar from colonies was often refined back in the home countries, with distillable molasses as a secondary product). In the 1700s the Bols company has records of both grain alcohol and the molasses-based “sugar brandy” being used as base spirits. Grape brandy was seen as more refined, and according to Vermeulen, the “owner of Bols around 1820 would prefer to use [grape] brandy and if it was too expensive would use grain alcohol instead.”

Column distillation that spread after 1830 allowed for any fermentable matter to be distilled to near neutrality and make a suitable base for liqueurs. The Netherlands and most of Europe switched to using neutral sugar beet-based spirit in the second half of the 19th century, after Napoleon heavily promoted the sugar beet industry in France. Today neutral sugar beet spirit is the base of Cointreau.

France and Triple Sec

The most famous and well-respected orange liqueurs on the market today, Grand Marnier and Cointreau, don’t come from Curacao or from the Netherlands, but from France, and it seems to be in France where Curacao liqueur evolved into triple sec liqueur.

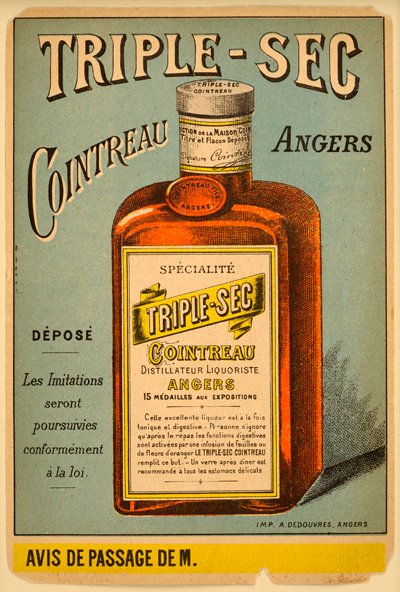

Cointreau initially produced a product called “curacao,” and then a “curacao triple sec” and then a “triple sec." According to Alfred Cointreau, the product labelling (and it seems the sweetness levels and possibly accent flavors) evolved over the years:

1859

- Curacao

- Curacao ordinaire

- Curacao Fin

- Curacao sur fin

1869

- Curacao Triple-Sec

1885

- Triple-Sec

Cointreau cites 1875 as the creation date of its orange liqueur, which is made with both bitter and sweet orange peels. Grand Marnier cites 1880 for its blend of cognac and orange peels. Both of these brands now shy away from the words “Curacao” and “triple sec,” on their labels.

The brand Combier claims 1835 as its creation date, with “sun-dried orange peels from the West Indies, local spices from the south of France, alcohol from France’s northwest, and secret ingredients from the Loire Valley – a formula that became the world’s first triple sec: Combier Liqueur d’Orange.”

But to what are the “triple” and “sec” referring?” The “sec” is French for “dry,” and the “triple” could point to several things.

Alexandre Gabriel, president of Cognac Ferrand, says that in conjunction with cocktail historian David Wondrich, they researched the history of triple sec and curacao and found a listing from a 1768 Dutch-French dictionary that described an infusion (without redistillation) of Curacao oranges in probably-grain spirit, but by 1808 recipes appear for redistillation of the oranges in spirit.

Gabriel’s theory is that the triple refers to three separate distillations or macerations with oranges. His Dry Curacao product is described as, “a traditional French ‘triple sec’ – three separate distillations of spices and the ‘sec’ or bitter, peels of Curacao oranges blended with brandy and Ferrand Cognac.”

By Gabriel’s definition, the ‘sec’ refers to the drier-tasting (due to bitterness) oranges from Curacao, independent of the sugar content of the liqueur. A contrary opinion comes from Andrew Willett of the blog Elemental Mixology, who makes a convincing argument that the ‘triple sec’ is a level of dryness from sugar on a scale from extra-sec, triple-sec, sec, and doux (‘sweet’).

Willett also proposes that the ‘triple’ could indicate three types of oranges: many French brands call for both bitter and sweet oranges in the recipe, plus some add an orange hydrosol (water-based orange distillate). That an early product from Grand Marnier was called Curacao Marnier Triple Orange could help support this argument. Willett concludes in another post that a “Curacao triple sec” is “Curaçao liqueur that is both triple-orange and sec.”

So “Curacao triple-sec” may refer to three distillates that include Curacao oranges, three types of oranges including Curacao in a very dry liqueur, or just a specific level of dryness from sugar of a Curacao liqueur. As mentioned, these differences and definitions are not meaningful today.

Curacao comes in many colors, but coloring of the liqueur is more traditional than one might imagine. It dates back at least to the early 1900s (when the liqueur was colored with barks) and some cocktail books including the Café Royal Cocktail Book from 1937 specify using brown, white, blue, red, and even green Curacao in various recipes.

Today, bartenders might consider each part of the liqueur in deciding which brand is appropriate for a particular cocktail: the orange flavor, the base spirit, the proof of the liqueur, and yes, the color. There’s a whole rainbow to choose from when choosing an orange liqueur.

Below Here is the Original Post that I updated with the above information. Please ignore it! It's just here for legacy purposes.

I tried to answer that question as best as I could in my recent post for FineCooking.com.

Four hundred years ago, the Dutch were some of the world’s greatest traders and, not coincidentally, great distillers. They’d preserve the spices, herbs, and fruit brought home on ships in flavored liqueurs and other spirits. Curacao was one of those liqueurs, flavored with bitter orange peels from the island of the same name. At the time, the liqueur would have had a heavy, pot-distilled brandy as its base.

Then the French came along (a couple hundred years later) and invented triple sec. The “sec” meaning “dry,” or less sweetened than the Dutch liqueur. The origin of the “triple” is still up for debate, but the two leading schools of thought are “triple distillation” versus “three times as orangey”. Triple sec was also clear, whereas curacaos were dark in color.

Today, triple secs are usually still clear (made from a base of neutral spirits), whereas curacaos may start that way and be colored orange, blue, and even red. Cointreau is probably the most recognized brand of orange liqueur in the triple sec style, and Grand Marnier, despite being French, is more in line with the Dutch curacao style as it has an aged brandy base.

Nerds: Do you think that's an accurate summation?

The full post is here, and it includes a recipe for the White Lady cocktail.

-

Sherry is to Tequila as Vermouth is to Whiskey

Sherry and tequila are showing up together on more and more cocktail menus. I wrote a story about that in the Sunday, February 20th San Francisco Chronicle.

(Del Rio cocktail by Josh Harris of the Bon Vivants. Photo: Craig Lee)More drinks including Tequila and Sherry

Camper English, Special to The ChronicleSherry and Tequila are having a love affair. Bartenders are using more of each ingredient lately, but increasingly you'll see the two sneaking off in a drink together, canoodling in a corner of the cocktail menu.

One of the first outward signs of this attraction came in the form of La Perla, a drink created several years ago by beverage consultant Jacques Bezuidenhout, which is still on the menu at Bourbon & Branch. The cocktail contains reposado (lightly aged) Tequila, manzanilla Sherry and pear liqueur.

A not-too dissimilar flavor combination has popped up recently. At the Hideout at Dalva, a tiny backroom cocktail bar in the Mission District, Josh Harris serves the Del Rio. The drink is made with blanco, or unaged, Tequila, fino Sherry, St. Germain elderflower liqueur, plus a dash of orange bitters and a grapefruit zest.

At Gitane, the Sherry-centric Claude Lane restaurant, bar manager Alex Smith and two other bartenders collaborated on a drink called the Flor Delice, made with reposado, manzanilla, St. Germain and orange bitters, plus maraschino liqueur.

In New York, this combination shows up yet again on the menu at Mayahuel, a bar dedicated to Tequila and mezcal. The Suro-Mago uses blanco, manzanilla, elderflower and orange bitters, and adds a rinse of mezcal to give it a smoky touch.

Read the rest of the story and get the recipe for the Del Rio, a simple and delicious drink.