I was recently in Calistoga to meet with Baptiste Loiseau, cellarmaster for Remy Cognac. We had a quick interview early in the day but I wanted more info, so I ended up monopolizing his time after dinner. We spoke for a very long time (I promised it was "quick questions" but I think it went an hour) and I learned so, so much!

(However, please note that I wrote up this post working from my brief notes, rather than from a transcript, and it has not been fact-checked. )

The trip was to introduce the new permanent expression to the Remy line, Tercet. In this post I'll talk about the points of uniqueness of Tercet as well as Remy Martin cognac in general.

Tercent sits in the range as such:

- VSOP $46

- 1738 $60

- Tercet $110

- XO $200

Plus the older/fancy bottlings. Tercet is aged to the legal VSOP level (4 years) but is closer in average age to an XO, according to Loiseau.

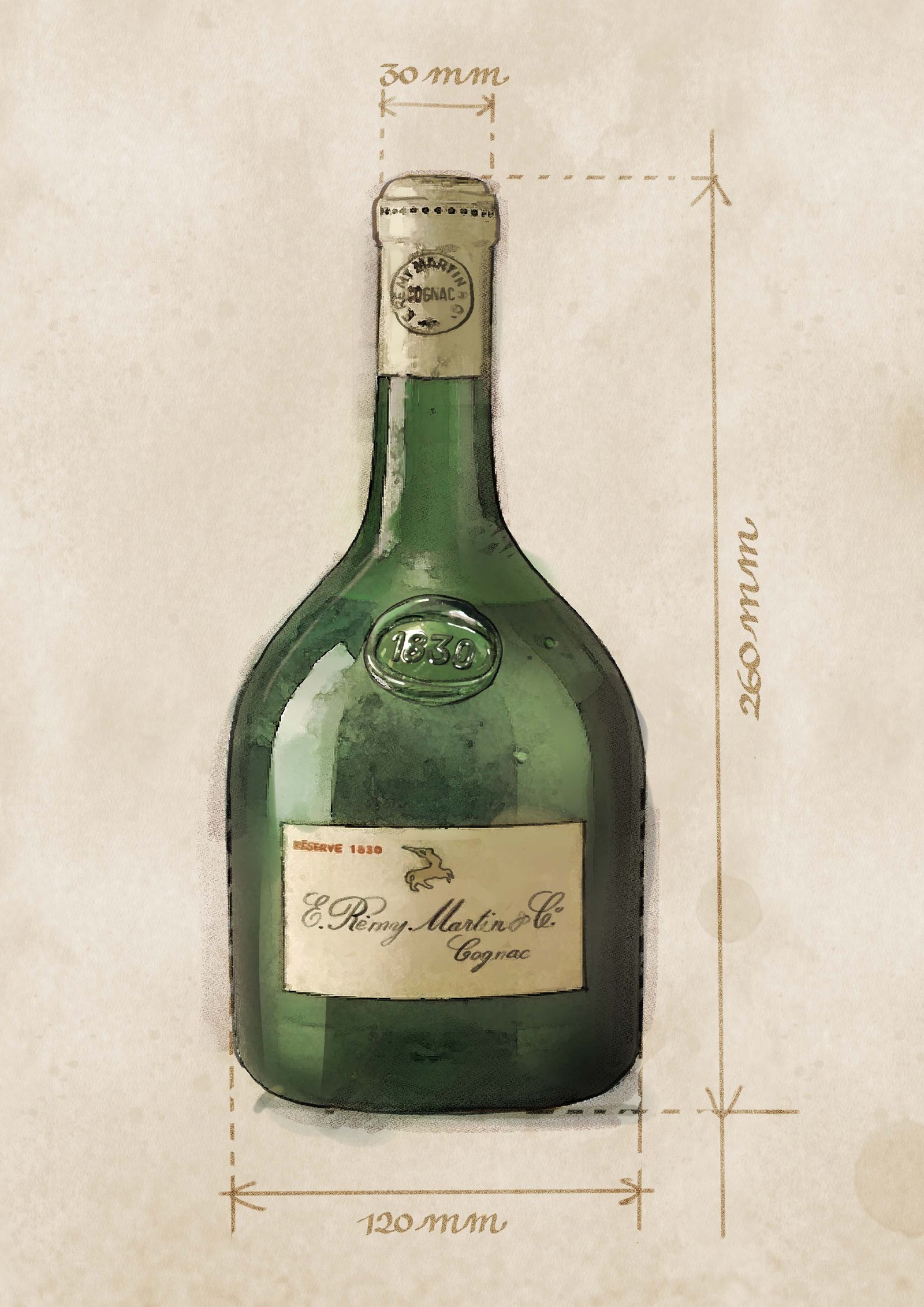

The marketing emphasizes "three artisans," – the wine master (grower), the master distiller, and the cellar master. The flavor profile notes emphasize it being "fruit-forward," "fresh," and with a "long and complex finish." And to me, the bottle evokes earthiness/rusticness/artisanship.

As always, I'm interested in why a brand story and flavor profile are described a certain way. In the process of asking what is unique about Tercet and why it's positioned in this way I learned tons of information.

The Why of Tercet

The brand found that many drinkers didn't know where cognac comes from or that it's made from grapes, even many fans and regular drinkers of cognac. (This is the case for many of the world's strongest spirit brands- people who drink Patron don't know it's tequila, people who drink Jameson don't know it's whiskey.)

Loiseau said, and this is the only direct quote I have in this whole huge write-up, "People are enjoying a brand or a category, but if we want them to choose cognac in future years [if/when they become more educated drinkers] we have to emphasize what makes it special."

To accomplish this goal, Tercet emphasizes grapiness/freshness in flavor, and the three producers on the label. And by emphasizing the producers on the label, this is a visual key to how it's made: it's made from Wine that is Distilled and Aged.

As to how Tercet is positioned in the line, Loiseau said that the 1738 blend more emphasizes woody notes while Tercet emphasizes the fruit.

Tercet is bottled at 42% ABV, which is higher than nearly all cognac. I asked Loiseau if the marketing department had come to him with a brief of needs list of a higher proof, but he said that no – he approached marketing with his desired proof for Tercet and they liked it as a point of differentiation.

Winemaking

Loiseau's history is as an agronomist and oenologist – in other words, an expert in winemaking. The marketing copy seems to imply that Loiseau discovered wines from the artisan winemaker Francis Nadeau that were super interesting and he put some aside for special experimentation, but the reality is a different (not a huge surprise there, but much easier to explain). Loiseau estimated that Nadeau's distillates make up just about 1% of the liquid Remy buys overall.

On the other hand, Nadeau sells about 90 percent of his eau de vie to Remy, and his father and grandfather sold to the house also. So the company and the winegrower have a close and great working relationship, as well as an expertise in winemaking.

The new blend Tercet doesn't have a distinctly large amount of wine from Nadeau's vineyards – his emphasis on the packaging/marketing of the new release is a nod to his involvement of growing/pressing/fermenting/distilling the specific style of grape/wine used in the Tercet blend.

Sidebar: For the wines purchased by Remy Martin, the winegrowers distill at their own properties. Remy only distills wine from their own wineries.

Loiseau said that when he was working on this project, previous cellar master Pierrette Trichet expressed concern that when the distillate aged and evolved, it might not match the Remy Martin house style. But it all worked out: They followed this eau de vie along as it aged until they felt it was ready to take the spotlight. Then they had to make more of it.

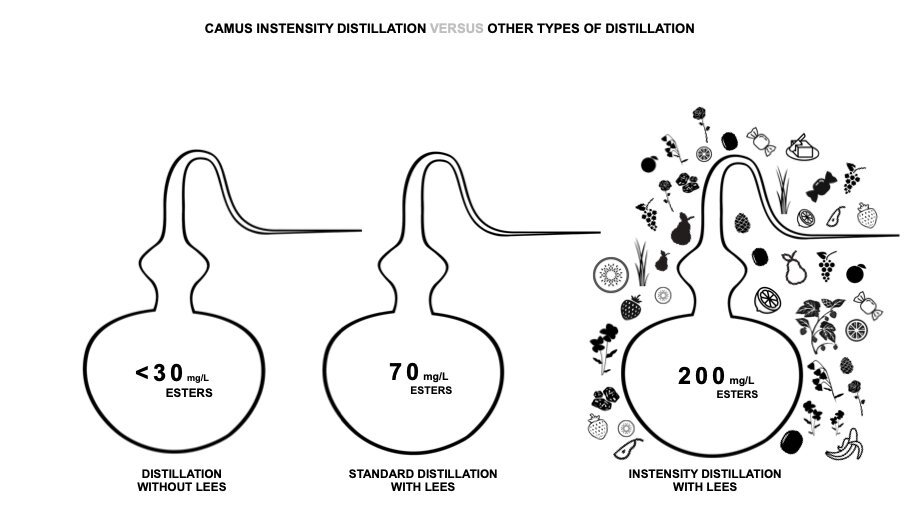

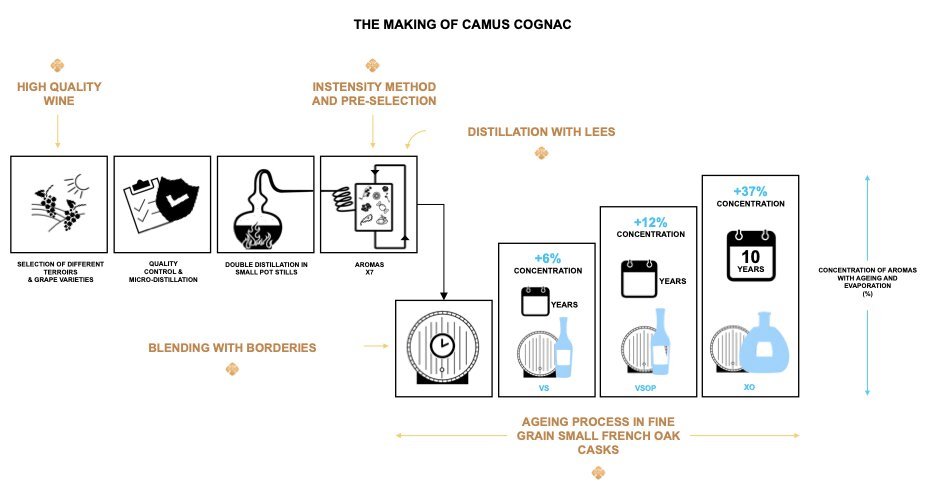

Remy buys wine from about 800 winegrowers. They grow the grapes, press the juice, ferment, and distill them. They do this in the style of the cognac house they will sell to – for example some cognac brands distill on the lees (yeast and grape skin bits post-fermentation) and others do not. So going into the harvest, the winegrowers are given directions from the brands they plan to sell to about how they should make their distillates. Loiseau mentioned an "annual winemakers meeting" which sounds exciting to me, but you know, I'm special.

Many growers sell to multiple brands, so they are making different styles of eau de vie in one facility. (Fascinating! My idea of how this works was that after distillation various brands come and just pick and choose what they want from a bunch of vats of eau de vie, but rather it's "here's your order, make sure it's to your specifications, and then pay us!")

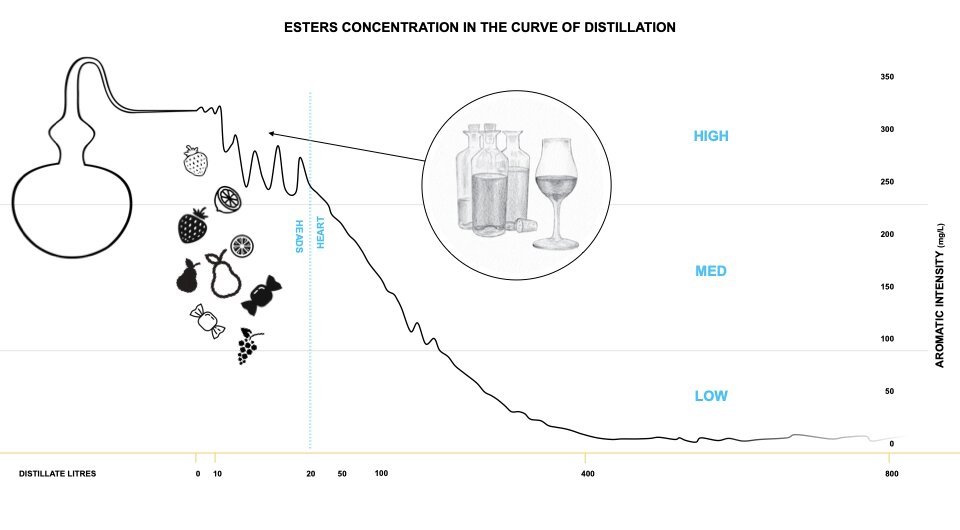

So Loiseau and his team must talk to all the growers each year and give them directives – not just specific to their house style, but specific to the wine produced at each vineyard: his team will taste the wines made at a vineyard and tell the local distiller to remove X amount of heads when distilling. A winemaker with a very good wine may be told to keep in a larger part of the heads, while a bad batch of wine will result in being advised to keep a much smaller percentage of the heart and discard more of the heads. Loiseau says that only more skilled winemakers can achieve the style of wine they're looking for (I think he was saying the type of wine specific to Tercet at this point in the conversation), so not everyone is advised to distill their wine the same way.

Only after newly distilled eau de vie is produced do people from Remy evaluate it and choose to buy or reject the eau de vie, so the the winemakers don't actually have to take this advice on how to make it. Remy pays more for distillate that has a potential for longer aging, so I wondered if winemaker/distillers try to include more of the heads than they should. Then the winemaker would have more distillate to sell if they keep in more of the liquid, but Loiseau essentially dismissed this as something that doesn't really happen. They work with winemakers every year to ensure they know what the parameters are going in, so why risk it?

Aging

Remy has two different types of contracts, for aging either at the winemaker's site, or aging in Remy's cellars. In either case, it's aged in Remy-purchased casks. Loiseau says the reason for not aging it all themselves isn't necessarily space issues, but for diversity of cellars and resulting flavor.

Cognac is aged in a combination of dry and wet cellars, but Loiseau says that the balance between cellars is not a point of differentiation for Tercet anyway. The barrels they use for Tercet are the point – they're older and give less wood impact in order to let the fruit shine through.

Make It Rich

Tercet is also meant to have a richness to it, coming from distilling on the lees that bring more fatty acids to the final product. However when you distill on the lees, you have to pay extra careful attention to saponification – when you dilute a spirit too quickly it can make unwanted soapy flavors. Loiseau says that for cognacs not distilled on the lees you can do a faster dilution scheme compared with the stuff distilled on the lees.

Another thing I learned is that you don't proof in the barrel directly due to the fear of saponification – those molecules (don't recall what type they are) tend to stick to the barrel and particularly when you reuse barrels the next thing to age in it is impacted by soapy flavors sticking around.

Even within a line of products from one maker, there are different dilution rates – unlike in some spirits, producers do not simply let a cognac age then add enough water to bottling proof. The richer products aging for longer get a slower rate of dilution: They add some water before putting the fresh distillate into barrels, then more at certain lengths of aging, then slightly adjust the proof before bottling.

Loiseau said that this gentler dilution rate also impacts barrel proof: To cognacs that are destined for younger products, you add water before putting them into the barrel the first time. This meets the ideal or target entry level proof found to best in cognac (overall in the industry – much like in bourbon, barrel entry proof was studied and a common standard was determined). Remy VSOP and 1738 go into the barrel at this standard proof.

So, for future fattier Tercet, less water is added at the outset, resulting in a higher barrel proof. Higher barrel proofs (higher than the ideal standard) do not, as you'd assume is the case, mean more wood extraction from the barrel, but less. So this means that there will be less wood flavor impact on this blend. And this helps ensure that the blend has the less-wood-more-fruit flavor they're going for.

Loiseau used the word "gentle" to describe how Tercet is produced to reach the desired flavor profile and said they use a gentleness in other ways too: There's a gentle pressing of the grapes to get a clearer juice/wine, a slower fermentation (temperature controlled) to keep more delicate aromas in the wine, a slower speed of distillation (longer warm-up), and slower water reduction scheme. So we can see that a cognac maker can identify the end product that they want to make and adjust many factors that will steer it toward that end – in the fermentation, distillation, aging, and dilution.

Dear Reader: This was so much new, exciting, revealing, and mind-blowing information – and most of it explained to me over the course of a single hour – that I was jacked up on science at 11pm and couldn't get to sleep for hours, despite all the cognac. Of course, on rereading this post I could add another 20 questions about how Tercet's wine, distilling, and aging schemes differ from those of 1738 in particular, but that will have to wait for another opportunity I hope to get one day.

The Flavor of Tercet and Why

As mentioned above, Tercet is meant to emphasize fruitiness, freshness, and a long finish.

Distilling on the lees is meant to give the cognac body – softness and also a nuttiness, in addition to a potential for longer aging.

The grape and fruity flavors are emphasized by gentle handling of the liquid to ensure more of the raw material notes stay in the liquid rather than become covered up or evaporate off.

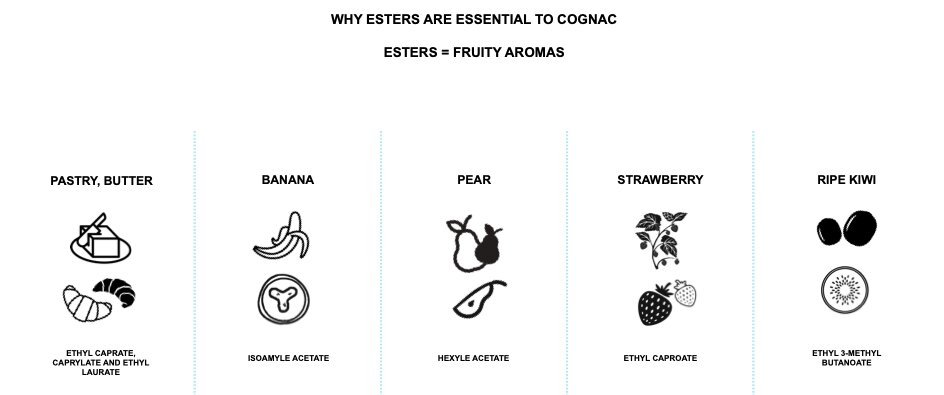

The fresh: notes Loiseau is talking about are actually tropical/exotic fruit notes like banana, pineapple, mango, and lychee.

The higher proof of 42 percent ABV helps these notes pop out first – on nosing they quickly pop. And then it's time for that long finish – tons of Christmas cake, ginger, nutty, nutmeg and spice notes come out. These come in part from the fatty acids there from distilling on the lees. Loiseau noted that the base notes are present in Tercet while the woody, tannic notes of the barrel are not emphasized in the blend.

This long and spicy finish comes from using older cognac in the blend that has had time to develop this complexity and a rancio notes. When we added ice to the cognac (which I was hesitant to do) the extra 2% ABV helped it stand up better to dilution, the creamy body remained in the brandy in the glass, and leathery sort of notes and that ginger dominated. It had the notes of many peoples' ideal Old Fashioned.

Thanks to Remy Martin and Baptiste Loiseau for an awesome opportunity to geek out on cognac!