I wrote a story for VinegarProfessor, sister site to AlcoholProfessor, about using vinegar in cocktails. It contains some very good advice from several bartenders.

You can read it here.

I wrote a story for VinegarProfessor, sister site to AlcoholProfessor, about using vinegar in cocktails. It contains some very good advice from several bartenders.

You can read it here.

Well, more or less. In my latest for Food & Wine, I trace the origin of both drinks and how they each deviated from the original Cocktail.

Read it here.

For Men’s Journal, I wrote about the choice of sparkling water for your whiskey highball.

Read it here.

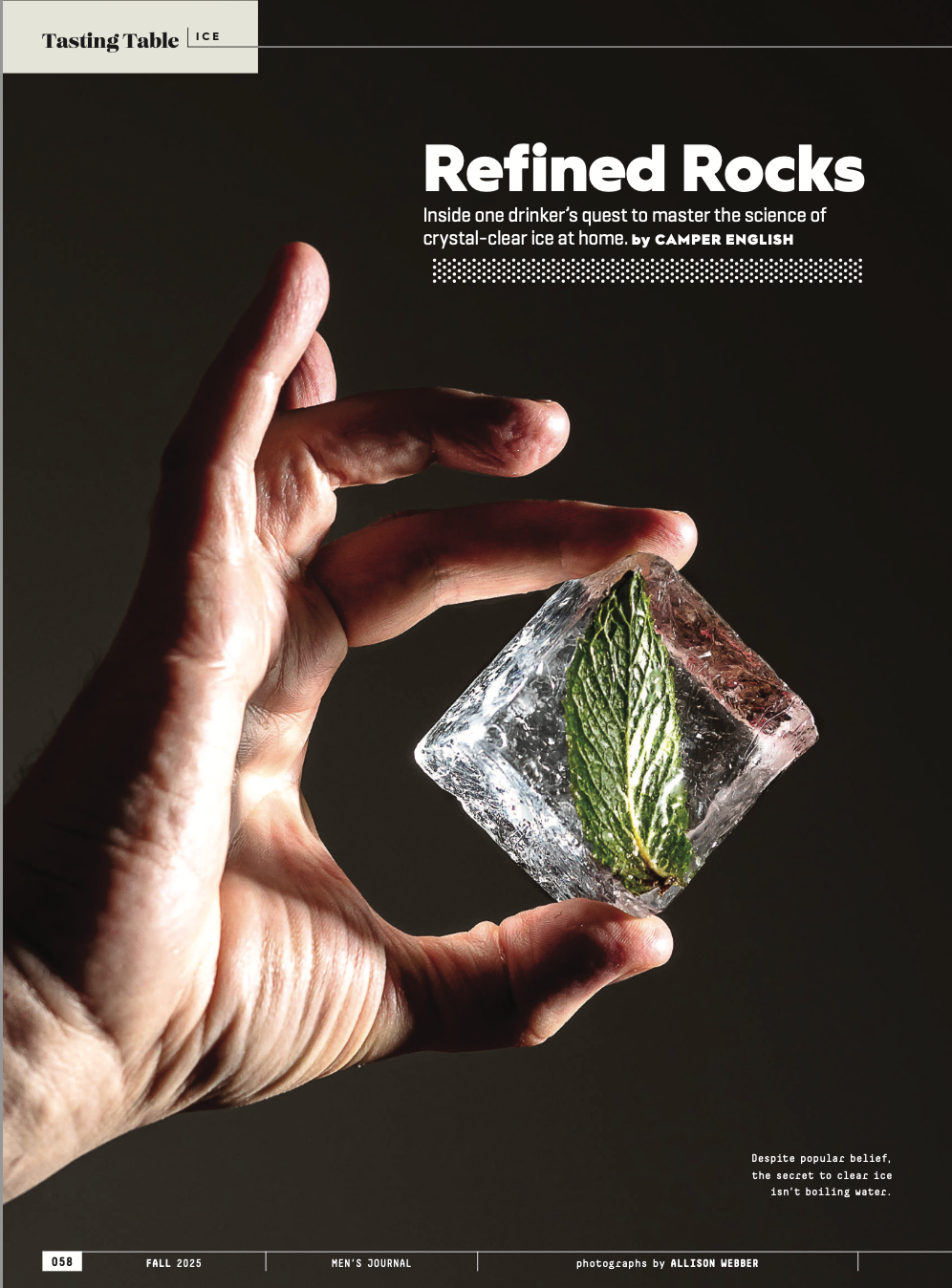

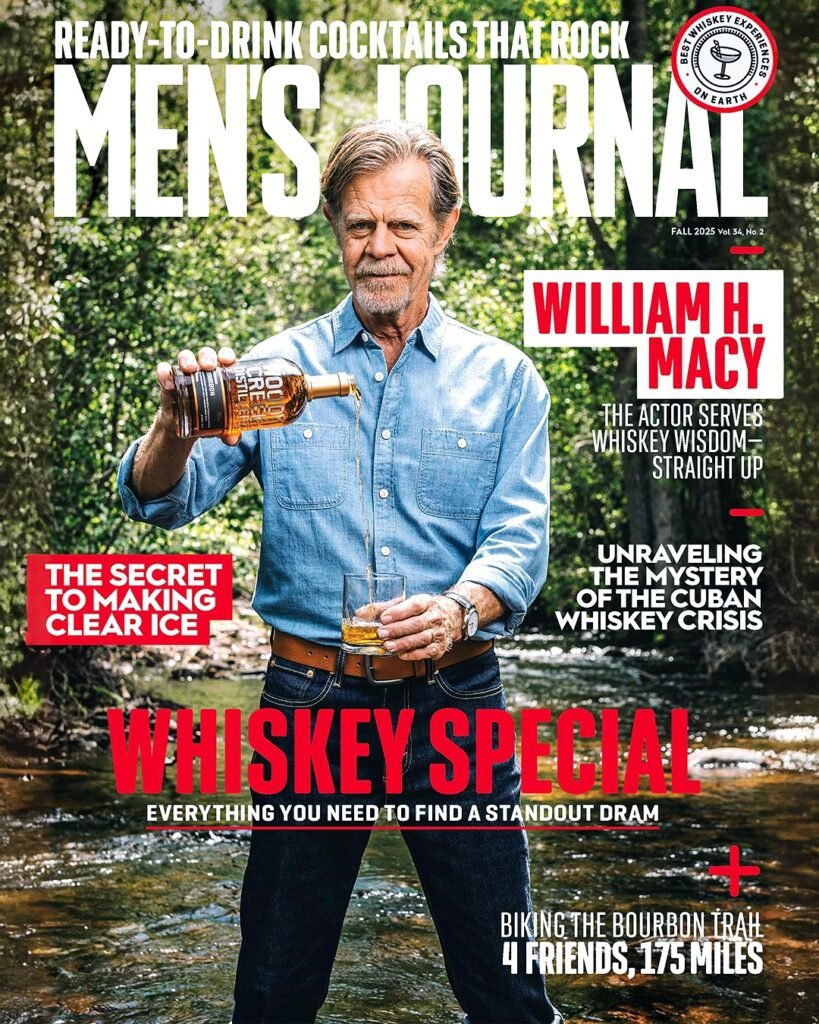

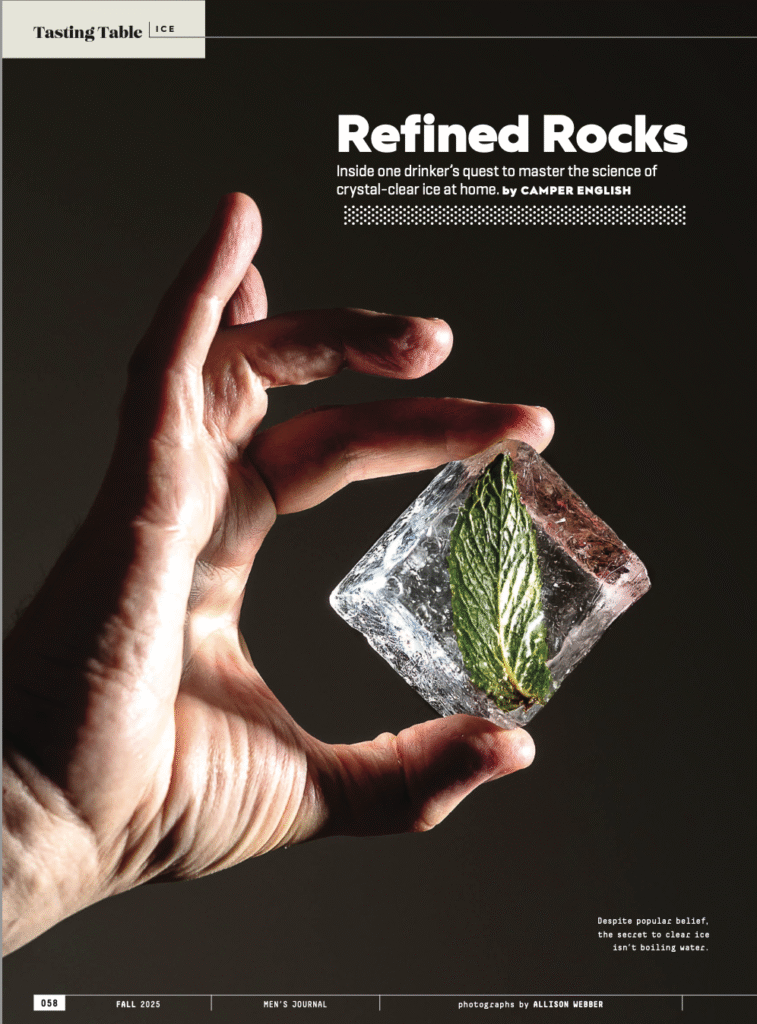

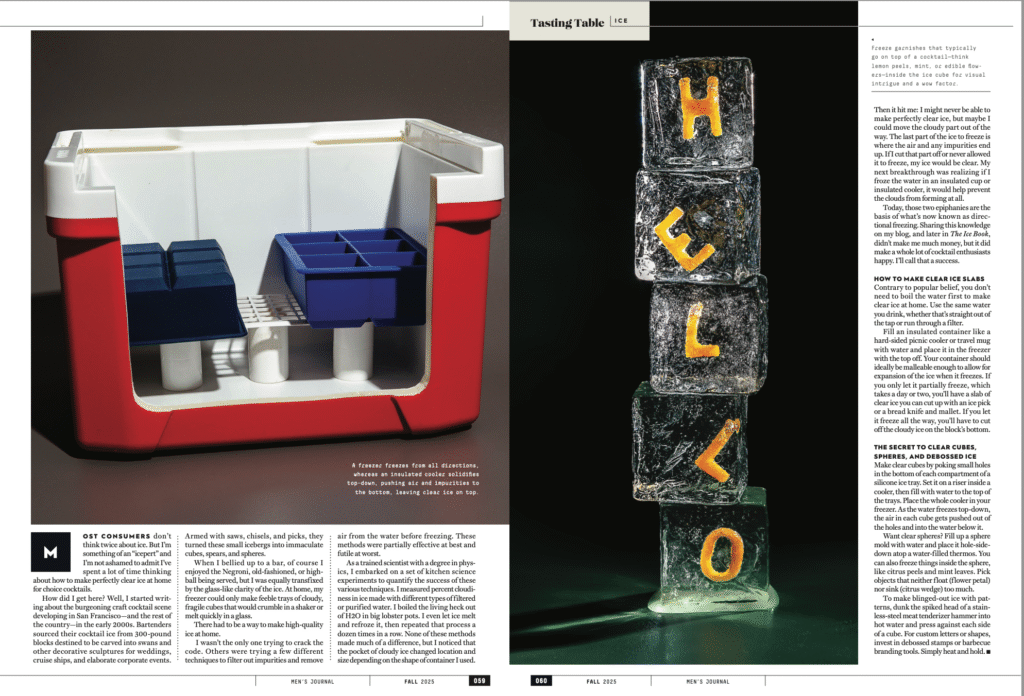

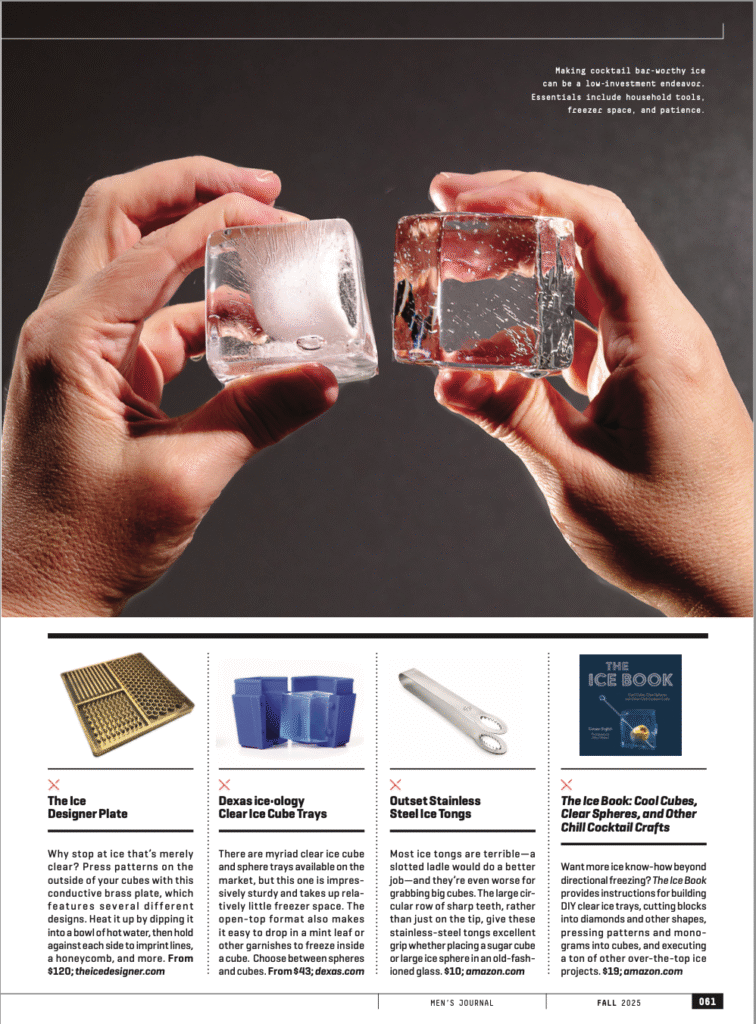

I wrote up a relatively short article for Men’s Journal’s Fall 2025 issue but hadn’t seen the final copy until just now: turns out they gave it a four-page spread in the print magazine.

As always the photographs from Allison Webber are stunning. Here’s a preview.

I’ll be giving a short talk at the event “Celebratory Bubbles, Not Eye Troubles” at the Museum of the Eye in San Francisco on December 28th. It’s an annual New Year event.

My talk (probably a short one of 20ish minutes) is “Eye-Openers, Corpse Revivers, and Anti-Fogmatics: The Medicinal Morning Cocktail.” It’s based on stuff from my book Doctors and Distillers, of course.

More info and link to tickets is here.

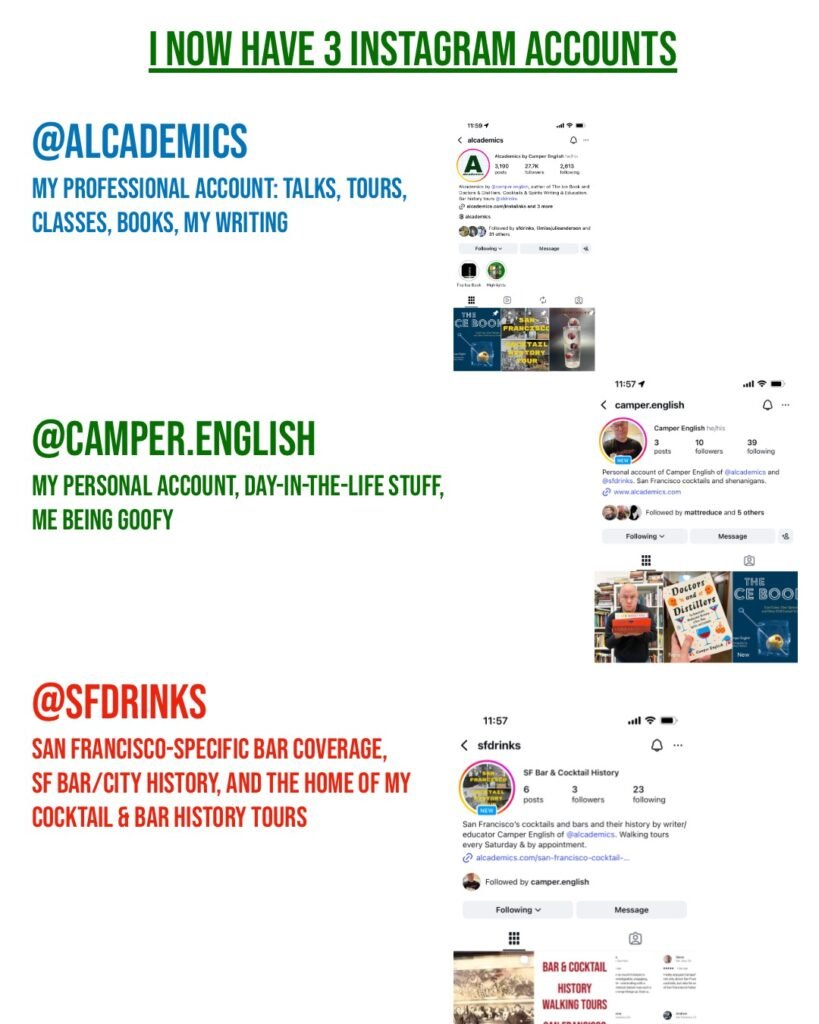

My Alcademics Instagram account is looking a bit… scattered between my personal posts, promoting my cocktail history tours, books I’m reading, and stuff that comes in the mail. So I’ve decided to split it up:

@Alcademics is my business account where you’ll hear news and updates about my talks, tours, classes, books, and writing.

@Camper.English is my personal account; day-in-the-life type stuff where I’ll post about the books I’m reading, works-in-progress, what I’m up to, goofy stuff.

@SFDrinks will be for San Francisco drinks content – bars and cocktails in San Francisco, and the home of my Cocktail and Bar History Tour. I’ll share historical stuff as well as what’s going on around town now (if I can keep up with all that).

Or, if you just want to keep current with the basics, I have a monthly email list where I post recent articles and my talks and events, no need for a million pictures of everything.

My latest for AlcoholProfessor.com is the story of how the scientific quest to produce artificial quinine led to the invention of chemotherapy. It’s a cool story IMO. Read it here.

I gave some quotes about ice for a story on the website Shortlist. They also interviewed other people who are correct in saying that better ice makes a better drink, and that attention to quality of ice signifies attention to quality of cocktails.

I have the final quote in the story, in response to the reporter’s question about the cost of fancy ice increasing the cost of cocktails:

“Is it an extra cost? Yes. But really, it’s hard as a consumer to assess the individual costs of each ingredient in a cocktail. A bar could lower the price by serving it in a paper cup, too, but then it wouldn’t feel special. And that’s what this creativity with ice is about, too”.

As always, you can learn more about The Ice Book here.

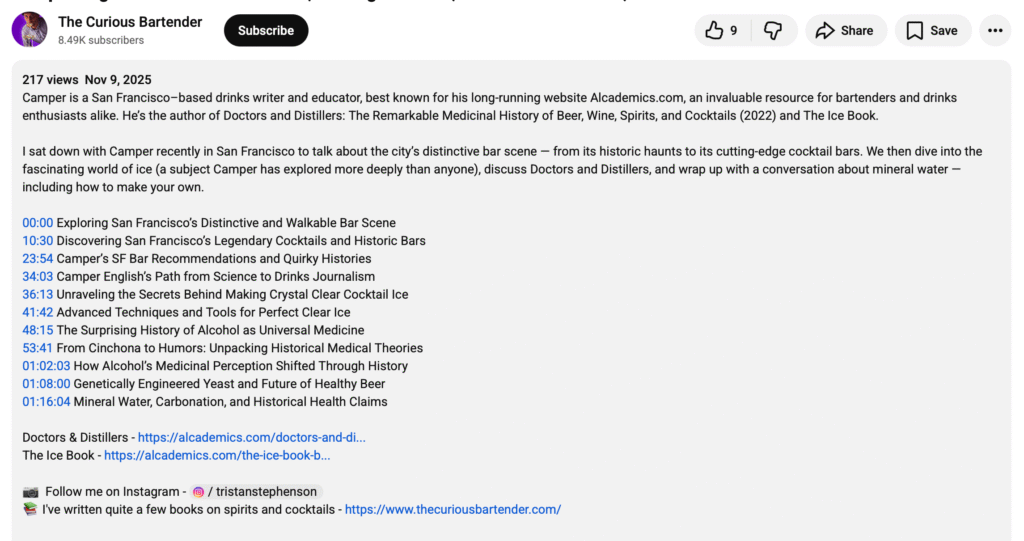

I was a guest on Tristan Stephenson’s The Curious Bartender Podcast last week, talking for nearly two hours about.. a lot of stuff.

You can find the podcast on your favorite service from The Curious Bartender website, or to go directly to the YouTube video of it click here.

In my latest story for Food & Wine, I tell how those big clear ice cubes you find in cocktail bars are made. They don’t just pop out of a machine – every big clear cube you’ve had has been hand-harvested or hand-cut.