The main water factors that affect ice clarity in an ideal environment:

- Gasses in water

- Minerals/other impurities in water

Factors of the freezing environment that also impact clarity:

- Rate of freezing (warmer temperatures better)

- Shape of container, which impacts whether the last part to freeze will crack the ice (as it does in a typical ice cube tray)

- Jostling/moving of the cooler in a home directional freezing system (cooler with the top off) as this causes bubbles to form earlier

I've been studying each of these factors carefully, as I may be contributing a section on the science of ice to the Oxford Companion to Cocktails and Spirits (which hasn't been edited/approved yet, and isn't due out for a while so don't get too excited).

One factor that has always confounded me is the gasses in water. We know from observation that gas in water becomes trapped in ice in the form of bubbles, whether that's in the center of an ice cube or the bottom of the block using a cooler in the freezer.

Most kitchen sinks have aerators on them that add more air to water, so that's a factor. But there are also lots of theories (boiling water, freezing then melting then refreezing) that are meant to minimize the air in water.

My issue has always been: If trapped air in water is water's natural state, then if you boil the water to eliminate that air, wouldn't air just be re-absorbed into the water when it returns to room temperature?

Dave Arnold in Liquid Intelligence asserts that you should boil the water, put it in your cooler, let it cool a bit, and then put it in the freezer. I was doubtful that this actually helps, but Dave Arnold is usually right, so I finally decided to test this.

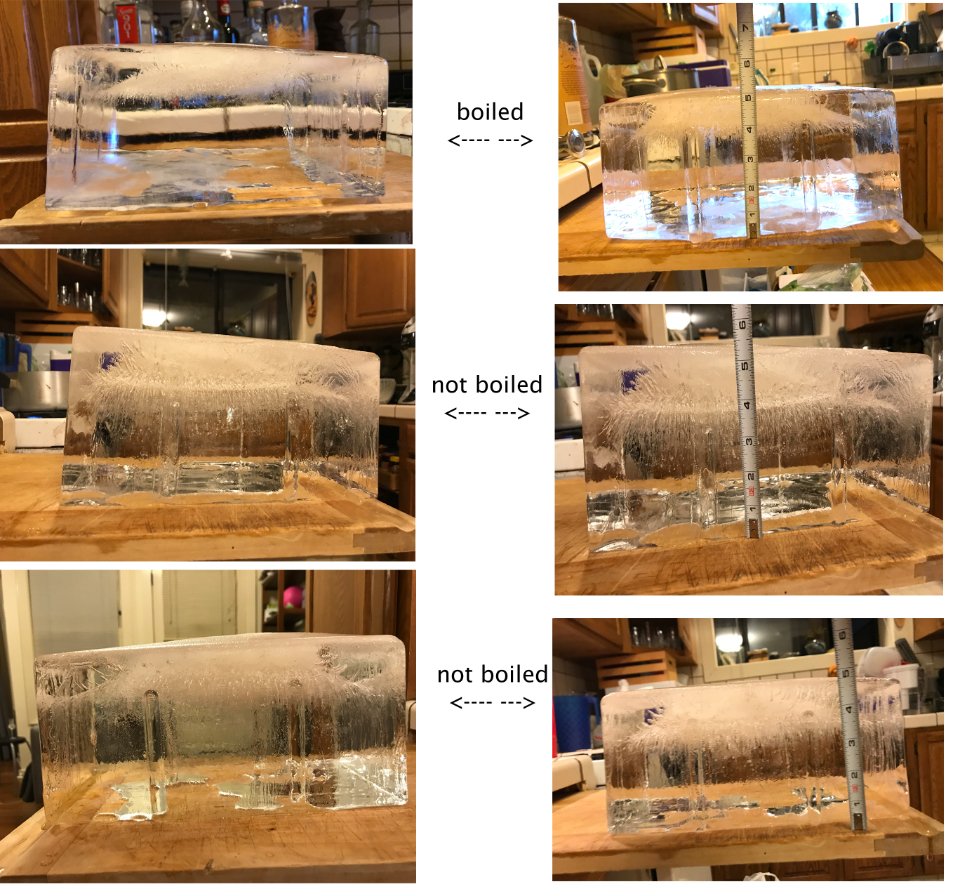

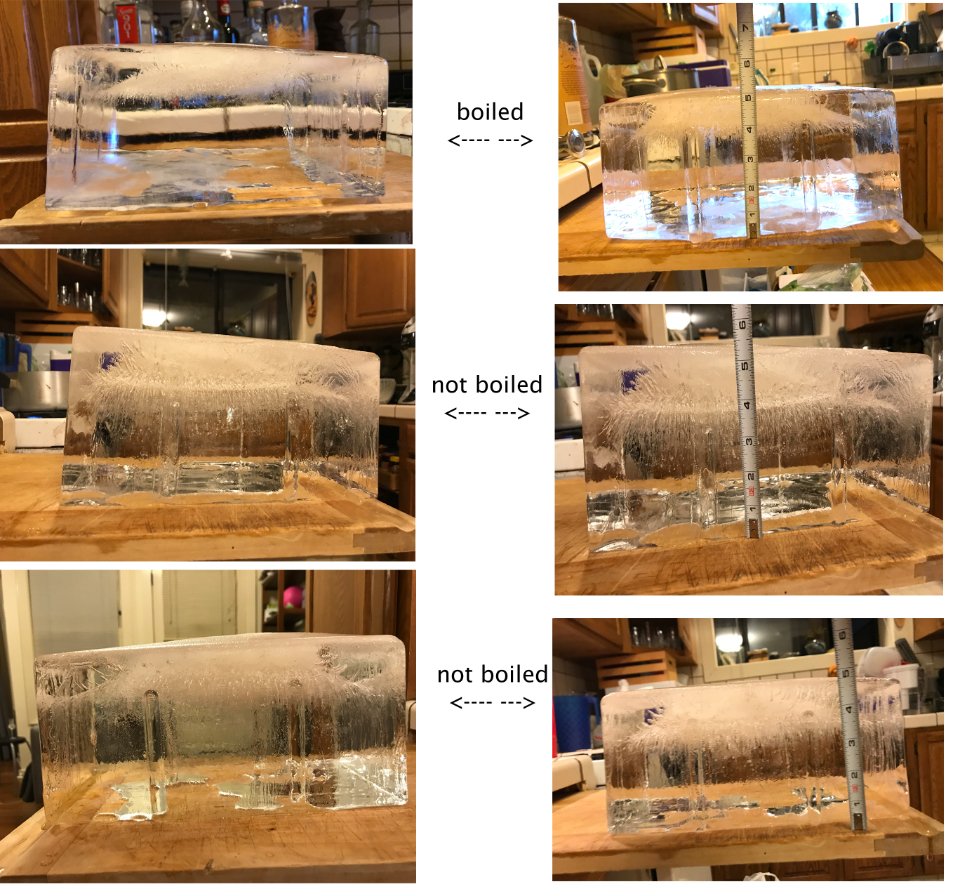

Click on the image below to expand it greatly.

Experiment

For the first block of ice, I boiled tap water briefly, put it into the cooler, let it cool down for several hours, then froze it on the highest (warmest) setting in my home freezer.

For the second block of ice, I used tap water that I poured into the cooler, let it set out overnight, and froze it the same way. The theory of letting it sit overnight was that the air bubbles introduced via the sink aerator and pouring water from one vessel to another would fizz off naturally.

For the third block of ice, I put tap water through a Brita filter, and was generally extra careful to not introduce air by splashy pouring. (I was hoping the filtering and light handling would further reduce aeration.)

Results: The fully cloudy, opaque (unusable) section of of the block is slightly reduced in the boiled water vs. unboiled. If I were making ice in an industrial capacity using coolers, it probably wouldn't be worth the time/effort/heat to boil the water to produce rather than getting it done 5 hours earlier and having a half an inch less usable ice.

However, the amount of thin streams of bubbles in the clear part, which look okay but not perfect when cut into cubes (though a bit more dramatic in pictures), seems significantly reduced in the boiled water block.

Conclusion: Boiling water before freezing in the directional freezing system does appear to improve the clarity of ice, in particular by eliminating bubble streams in the section of ice just before the solidly cloudy final bit.

It does not improve ice clarity on its own more than directional freezing does in the first place, and therefore won't replace directional freezing (and boiling water was the first experiment I did in trying to make clear ice eight years ago), however it can make directionally-frozen ice better.

It seems the natural aeration of water poured from the sink is reduced, though certainly not eliminated, by boiling the water before freezing it.

A future experiment (not sure if I'll actually do it) would be to let the boiled water cool down to the same temperature as the unboiled water before freezing, though I doubt this would have any impact.

How will I change the way I make ice at home? I will not. I try to use filtered water, frozen in a cooler, removed after 2-3 days so the cloudy bottom part hasn't formed at all.