Years ago when I first heard of – and tried- Barr Hill Gin, it was a revelation. The gin is neutral spirits with added juniper and honey- that's it. The honey brings with it other aromatics from the flora the bees feed on.

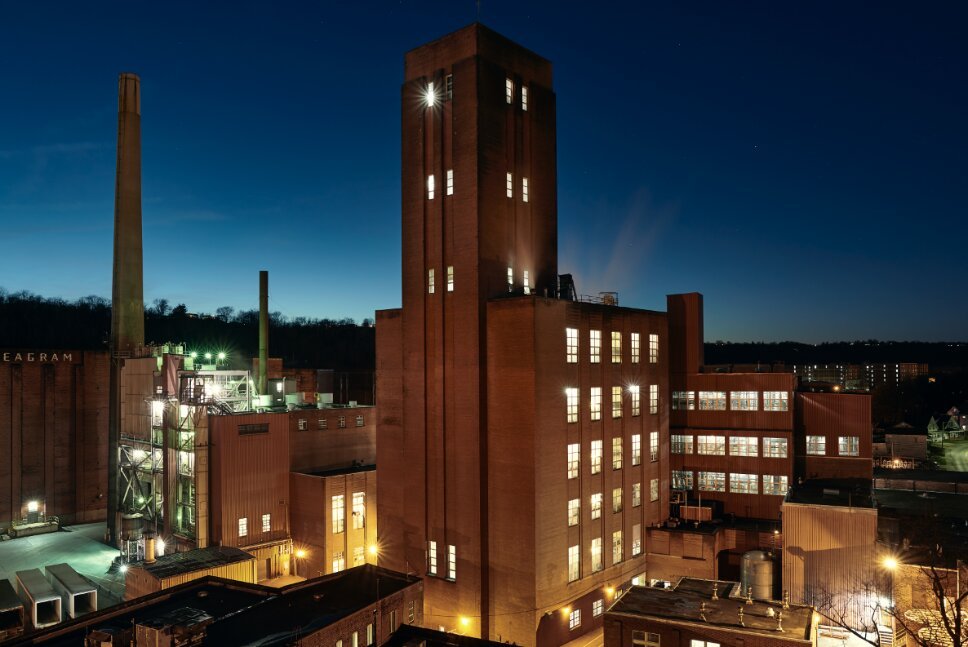

The gin is made by Caledonia Spirits in Vermont. A recent press release stated:

Caledonia Spirits is known best for its flagship gins, but the distillery's Barr Hill Vodka is a truly unique offering within the vodka category. Made entirely from raw northern honey and nothing else (~3000 lbs per batch), it’s distilled only twice – a stark contrast from many of the popular vodkas that get distilled 3-5 (or more) times and filtered to oblivion. Vodka was traditionally thought of as a spirit that became better the more times it was filtered, but doing so leaves a spirit that is completely odorless and tasteless.

Knowing just how beautiful of an ingredient the raw northern honey is, Caledonia Spirits wanted to flip tradition on its head and create a vodka that retains some of the flavor and aroma from its sugar source. Distilling and filtering it too many times would totally lose the honey flavor, but thanks to Caledonia Spirits’ unique process, the resulting vodka is fragrant and flavorful…yet not sweet at all. The honey tasting notes are very subtle, but they’re present enough to tell you that you’re not having the same neutral-tasting vodka that is so often served. Every year, Caledonia Spirits purchases 60,000-80,000 pounds of raw honey from beekeepers within a 250-mile radius of the distillery.

Sine then, the brand has released a vodka and a barrel-aged gin. I hadn't tried the vodka before. It is absolutely waxy almost to the point of greasy, with notes of Honey Nuts Cheerios, and I think I love it.

I was given the opportunity to interview Caledonia Spirits Owner/Distiller Ryan Christiansen, so that's just what I did!

Is the base of Barr Hill Gin purchased grain neutral spirits (plus honey and juniper)? Or is there distilled honey spirit in it also?

The base of Barr Hill Gin is grain neutral. It is then distilled in one of our two custom-built botanical extraction stills with Juniper. The spirit is proofed down with raw honey and our water.

Is Barr Hill Vodka 100% distilled from honey or is it a blend of GNS and distilled honey? If a blend can you give an approximate ratio?

Barr Hill Vodka is distilled entirely from raw northern honey.

I see several stills in the image on the website – the big pot and a small and tall finishing column. Which set-up do you use to make the gin vs the vodka?

Our gin is distilled in Irene and Ramona, two custom-built botanical extraction stills. Our vodka is distilled twice, once through a pot stripping run, then through the column still to 190 proof.

Is the honey sold by the pound? Is there a standard conversion for pounds of honey to liquid volume? Do you know the liquid volume of honey for the "60,000-80,000 pounds" you buy annually?

We purchase our honey by the 55 gallon drum, which holds about 650lbs of honey. In the last year we’ve used over 67,000 lbs to make our spirits. Each bottle of vodka requires 3-4 pounds of raw honey to make. Where we fall in that range from 3-4 depends on the batch size.

We do also sell our honey by the pound for use by bartenders and chefs.

For fermenting/distilling honey, do you dilute to a certain standardized sugar level (and do you measure this in BRIX) before fermentation? Can you say what that level is?

We pitch yeast at 24 brix, and ferment to dry.

How long does fermentation take? I imagine it's super fast.

Honey fermentations are much slower than grain fermentations, usually about 2-3 weeks to dry.

Do you temperature control the fermentation? Do you let it go longer into a malolactic fermentation? If not, is there a reason, such as it becomes disgusting?

We control fermentation temperatures with a water jacket on the fermenter. Honey fermentations don’t need much cooling. Our grain fermentations for whiskey production require much more heat extraction. We do not let our fermentations go to malolactic.

What's the ABV you get after fermentation?

Approx 12%.

You say you never heat the honey prior to fermentation, would heating it make it lose flavor/blow off volatile aromatics? (If I'm making a honey simple syrup should I not heat the water?)

This is a hard question to answer without a deep conversation. In short, it really depends on the honey. The botanical influence of the bees foraging varies significantly between honeys. As a general rule, keep the honey raw (below 110 degrees) when possible.

Obviously, our distillation process cooks our honey, but that occurs after fermentation. We’ve found it crucial to keep the honey raw during fermentation to develop and accentuate flavors that will stay intact through distillation.

And if you don't heat it and you do add water, is it very hard to mix? What do you use to mix it? Do you need specialized equipment for handling honey? It all seems incredibly sticky.

In our early days, it was a food grade shovel, bucket, electric drill, and a paint paddle with many trips up the ladder to the top of the fermenter. It was sticky and backbreaking, but it worked. We’ve added some fancy honey pumps and circulation lines in our fermenters that have made our lives a little easier. The honey is a sugar so with enough movement, it’ll dissolve. Keeping it raw certainly adds some challenges, but it’s essential for the finished spirit.

When purchasing huge volumes of honey as you do, how does that honey come? In what sort of container?

Beautiful reused and dented metal drums. Beekeepers never throw them away, they just keep traveling around the world. Even local honey is often delivered with old stickers and labels from all over the world.

Clearly as a vodka, you distill the fermented honey up to 95% to be a member of the category. I remember researching a while back to find that there wasn't a standardized terminology for what you'd call a lower-ABV honey distillate (other than "honey spirit") – some brands were calling their products "honey rum" for example. I'm wondering if you've heard any sort of consensus on this or your opinion on what to call honey spirit that isn't distilled to the vodka ABV?

I’ve heard a handful of terms. My favorite is Somel. This is an initiative led by a handful of distillers working with honey. https://somel.org/

Thanks to Caledonia Spirits for answering my questions!