Today's post is an excerpt from the new book Craft Cocktails at Home: Offbeat Techniques, Contemporary Crowd-Pleasers, and Classics Hacked with Science by Kevin Liu.

Today's post is an excerpt from the new book Craft Cocktails at Home: Offbeat Techniques, Contemporary Crowd-Pleasers, and Classics Hacked with Science by Kevin Liu.

The book is heavy on the science, which is awesome.

And you can download the Kindle version for free Thursday, February 28 – Saturday, March 2.

Liu gave me permission to reprint a huge section on water, which is below. Thanks Kevin!

Transform Tap Water into Magical Alpine Fairy-Water

STOP. Walk over to your sink, pour yourself a glass of water straight from the tap. Taste it. Does it taste delicious? Like fairies extracted dew out of fresh mountain grasses and carried the droplets in tiny hydrophobic blankets to your glass? Then skip this section. You have no reason to start messing around with your water.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) actually maintains more stringent requirements for tap water than the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) imposes for bottled water, so if your tap water ain’t broke, you might do more harm than good trying to fix it. BUT if your tap water—like mine—tastes like you’re licking a cast iron skillet with every sip, read on and I’ll show you how to recreate alpine fairy-water out of normal tap.

Myth: Water should taste like nothing.

This shouldn’t really come as a surprise to you, but bottled water manufacturers are lying to you. They promote the myth that bottled water is “pure” and that pure water, free from im“pure”-ities, tastes better.

Ask anyone who’s spent time in a chemistry lab: distilled water tastes nasty. It suffers from two major problems: (1) when air is removed from water, it tastes “flat” and (2) completely deionized and demineralized water is much more able to react with its environment, so it quickly picks up the taste of whatever it’s touching: typically plastic or the chemicals on paper cups (gross).

It’s not surprising that the most delicious waters in the world all contain signifi-cant amounts of minerals and oxygen. Consider what happens in nature: rain falls on a fairy-mountain. Let’s assume it’s pure at this point. As the water runs down alpine mountain fairy-streams, it passes over rocks and picks up dissolved minerals like calcium, sodium, potassium, and magnesium. And since oxygen is lighter than carbon dioxide, more oxygen gets dissolved in water than carbon dioxide at high fairy-altitudes.

These facts are not lost on bottled water manufacturers. Read the fine print on your favorite plastic hydration source, and notice how many of them contain minerals in addition to water. Most natural spring waters contain anywhere from 50 to 300 mg/l of stuff other than water, known in the industry as “total dissolved solids,” or TDS. Any water with TDS over 250 can be marketed as “mineral water” in the United States.

The United Kingdom even requires bottled water to contain minerals –

“under the UK Bottled Waters Regulations 2007 any bottled water that has been softened or desalinated must contain a minimum of 60 mg/L cal-cium hardness.”

When you start dealing with the mass production of water, consistent quality becomes a concern. It’s often easier for industry types to totally distill water and add minerals back into it rather than design filtration processes to produce a specific water profile. This process is called remineralization (more on this later).

Myth: All bottled waters taste the same.

In 2001, ABC’s Good Morning America program conducted a blind taste test of tap versus bottled waters. Of the four waters tasted, 45% (the largest group) preferred New York City tap water over bottled brands.

But what if ABC just got lucky? Tap water can taste great if it comes from a good source and has been properly treated. But it can also easily pick up off tastes along the way from the reservoir to the faucet. New York tap water might start off great at the treatment facility, but the pipes at your house might be contributing metallic or organic off-flavors. Gross.

Fast forward ten years. In 2009, the investigative journalism organization Mother Jones ran a piece on Fiji bottled water that examined everything about the product from the socio-economic impact the product has had on the small island of Fiji to the brand’s claims that each plastic bottle actually reduces car-bon footprint.

As part of the research for the article, editor Jen Quraishi conducted a taste test of popular bottled waters using 10 tasters. The results? Volvic mineral water, Whole Foods Electrolyte Water, and unfiltered San Francisco tap came in 1-2-3, out of ten contenders.

Then, in 2011, the online current affairs Magazine Slate conducted their own blind taste-test of the four most popular bottled waters in the the United States. In their test, not only could the 11-member tasting panel easily differentiate between bottlings, they all clearly disliked tap water and there was a clear win-ner at the end of the experiment: SmartWater.

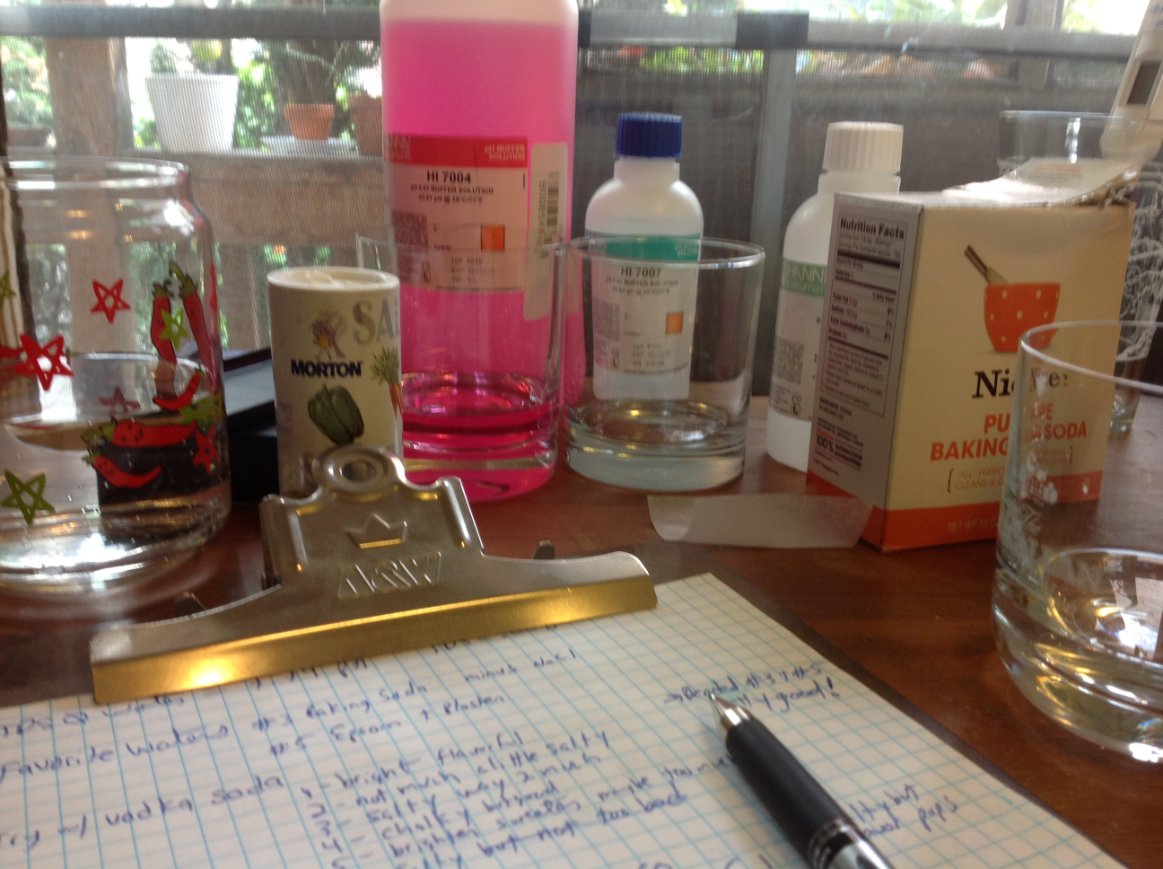

Reverse Engineering the Best-Tasting Waters

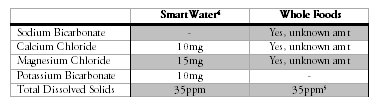

I took a look at how each of the bottled waters that dominated these two taste tests are made and made a startling discovery. Both the Whole Foods and SmartWater brands unabashedly admit they contain nothing more than puri-fied tap water, remineralized with a blend of minerals.

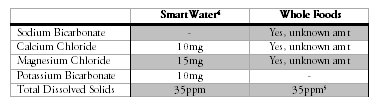

Luckily for me, inquisitive internet-dwellers had already taken the liberty of contacting both Glaceau (the makers of SmartWater) and Whole Foods to as-certain their mineral formulas. Glaceau happily obliged, as did Whole Foods, though the Whole Foods rep cited a total 3000 ppm mineral content that seemed totally off. So I bought a bottle of each and checked the numbers. Here’s all the available data, combined:

So in summary, two of the best-tasting brands of bottled water as judged in a blind tasting contained remarkably similar amounts and (probably) ratios of minerals.

And they’re easy to recreate at home, too. Here are some recipes for water. Ri-diculous? If you think so, you may want to stop this book reading here. It only gets more ridiculous.

Homemade Electrolyte (Fairy) Water

1 L Tap Water

10 g Homemade Electrolyte Concentrate (below)

Use a reverse osmosis or ZeroWater® filter to produce zero TDS water. Distilled should work too. If in doubt, test your “0 TDS water” with a TDS meter. Add the homemade electrolyte concentrate and shake violently.

Homemade Electrolyte Concentrate

1 L Tap Water

1.50 g Magnesium Chloride

1.00 g Sodium Bicarbonate

1.00 g Calcium Chloride

Use a reverse osmosis or ZeroWater® filter to produce zero TDS water. Com-bine. The mixture will stay cloudy for a while after you add the minerals, though it should clear up in time.

Notes:

• Use this concentrate so you don’t have to measure out 10 mg of minerals at a time. That would be annoying.

• Sodium bicarbonate is nothing more than baking soda. Potassium bicar-bonate can be substituted for people who are sensitive to sodium. Potas-sium bicarbonate is available through beer and wine homebrew stores.

• Calcium chloride is used both for beer/winemaking and in modernist cooking. Visit retailers who specialize in those ingredients for purchasing options.

• Magnesium Chloride is available as a dietary supplement. One product I found contained 66.5 mg per 2.5 ml serving, which means you would need 5.7 mL or just over a tsp per liter of water to make Electrolyte Concentrate.

• Avoid mineral tablets, as these contain binders and anti-caking agents that can affect flavor.

What Makes Water Taste Good?

With the exception of magnesium, all of the ions listed in the table above ap-pear in significant amounts in human saliva. However, our saliva’s composition doesn’t at all mirror the ratios presented here. Beyond this simple observation I can only speculate as to why this particular blend of minerals in this concentra-tion tastes especially good.

One possible explanation may lie in total dissolved solids. I found the following information on a forum post at Home-Barista.com. It quotes the Specialty Coffee Association of America’s (SCAA) Water Quality Handbook:

The test methodology was blind tasting by six tasters at the SCAA Lab in Long Beach. From page 31:

“In a tasting conducted by the Technical Standards Committee of the SCAA, coffee was brewed with different levels of TDS to determine if significant flavor differences existed and how much difference actually existed. … The same cof-fee, grind, and brewer were used and the same standard combination of miner-als was used. The only difference was the concentration of the minerals in the brewing water. The first tasting was conducted using three water samples: one contained TDS at a level of 45 mg/L, one at 150 mg/L, and one at 450 mg/L. The coffee that was brewed with 150 mg/L water was chosen as far superior by all who judged the coffee.

A second tasting was conducted using 125 mg/L, 150 mg/L, and 175 mg/L samples to determine if minor variations in water quality would have an effect on flavor and extraction. The minor changes in the TDS of water were unani-mously discernible by the panel. Acid and body balances were perceived to be off at both 125 mg/L and 175 mg/L TDS, and the 150 mg/L TDS brew was rated superior.”

So the coffee geeks seem to observe that the level of total dissolved solids is more important than anything else, with no concern as to which solids are actu-ally present. This didn’t make sense to me, so I reached out to a chemical engineer to find out more:

Joe McDermott on the Taste Chemistry of Water

Joe is a chemical engineer and a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University.

We got in touch because I heard your research area was in water. Tell me about that.

Sort of—I’m a chemical engineer by trade and my PhD thesis in Chemistry focused on colloidal particles in aqueous systems (the study of tiny stuff dis-persed in liquids). So I know a little bit about water chemistry, but it’s really exciting to be talking about it from the perspective of taste.

You’ve read through my ideas about making water taste better—what’s your professional opinion?

What makes water taste good is a really interesting question. From my under-standing of taste receptors, our taste buds are only set up to accept very specific tastes, like sodium chloride for salt or acids for sour.

I think you’re right that mineral content is important, but I’m not sure why from a taste perspective. My gut instinct is that the cation portion of the min-eral (the positively charged half) has less to do with taste than the anion side. If you look at the periodic table, a lot of the commonly found mineral cations show up really close to each other. There aren’t that many chemical reactions I can think of where Ca+ can’t simply be replaced with Mg+, for example.

Anions, on the other hand, can vary greatly in structure and complexity. They’re often structured organic molecules. Think about MSG—monosodium glutamate. The anion half is glutamic acid, an important amino acid that serves as a neurotransmitter and has the chemical formula C5H9NO4.

Why do you think ion concentration is important?

I work in a world where I need to know how much dissolved ionic material there is in a solution. It matters a lot more than the total dissolve mass because when ions dissolve in water, they change the charge of the water itself, which then changes how particles dispersed in the water behave. In the lab, we deion-ize our water to ensure. But if we get really good deionized water and let it sit out on the counter, it will measure out to 5.6 pH (relatively acidic). That’s be-cause atmospheric CO2 dissolves really readily in water.

So, does that mean that most water will turn acidic if it’s left out for a long time?

I haven’t tested this in the lab, but I would think so. In fact, that’s probably one reason why you see sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) or other bicarbonate minerals added to bottle water. Bicarbonates act as a pH buffer—that is, they make it so that it would require more CO2 to dissolve in the water before it actually became acidic. Think of it as insurance for nice-tasting water.

—

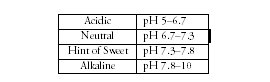

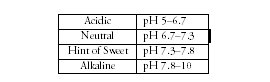

Here are some rules of thumb for how we perceive acidities found in the normal range for waters.

Resources, Tips, and Tricks

• You’ll want a digital scale capable of measuring down to 0.01 g (10 mg). Amazon carries many American Weigh models for about $10.

• My recipe for water is as simple as I could make it and seeks only to make good-tasting water. For many more recipes and resources for reproducing mineral and spring waters with unique taste profiles, see MineralWaters.org, Martin Lersch’s work on mineral water at his blog Khymos, or Darcy O’Neill’s book Fix the Pumps.

• If you can’t filter your water or create your own magical mineral water, at least let tap water rest for 20 seconds open to air before using. Most tap water is treated with chlorine, but chlorine escapes rapidly into the air, so it’s a good idea to let some of it evaporate off before drinking.

• Particularly hard water can create unsightly pectin gels or even create a buffering effect that could mess with pH. If in doubt, get a cheap total dis-solved solids meter (about $15 on Amazon) and check your water. When I checked my tap water, it came out to 350 ppm (yikes!).

Buy Craft Cocktails at Home: Offbeat Techniques, Contemporary Crowd-Pleasers, and Classics Hacked with Science by Kevin Liu on Amazon.com.

Buy Craft Cocktails at Home: Offbeat Techniques, Contemporary Crowd-Pleasers, and Classics Hacked with Science by Kevin Liu on Amazon.com.

The book focusses on the history and mechanics of the pre-Prohibition soda fountain. Though largely filled with information on sodas, it includes a chapter and some recipes on mineral waters.

The book focusses on the history and mechanics of the pre-Prohibition soda fountain. Though largely filled with information on sodas, it includes a chapter and some recipes on mineral waters.  The Water Project on Alcademics is research into water in spirits and in cocktails, from the streams that feed distilleries to the soda water that dilutes your highball. For all posts in the project, visit the project index page.

The Water Project on Alcademics is research into water in spirits and in cocktails, from the streams that feed distilleries to the soda water that dilutes your highball. For all posts in the project, visit the project index page.