At Tales of the Cocktail, I attended a seminar led by Ian McLaren and three scientists, all from Bacardi. It was called Genie in a Bottle: How Spirits Age.

Being part of a gargantuan spirits company they were able to call upon the science that had been done in the past and specifically for this seminar about how spirits change in the bottle. I think there is a general acceptance that in opened bottles stored for many years, spirits get a little bit flatter in flavor. In this seminar they took it way further than that.

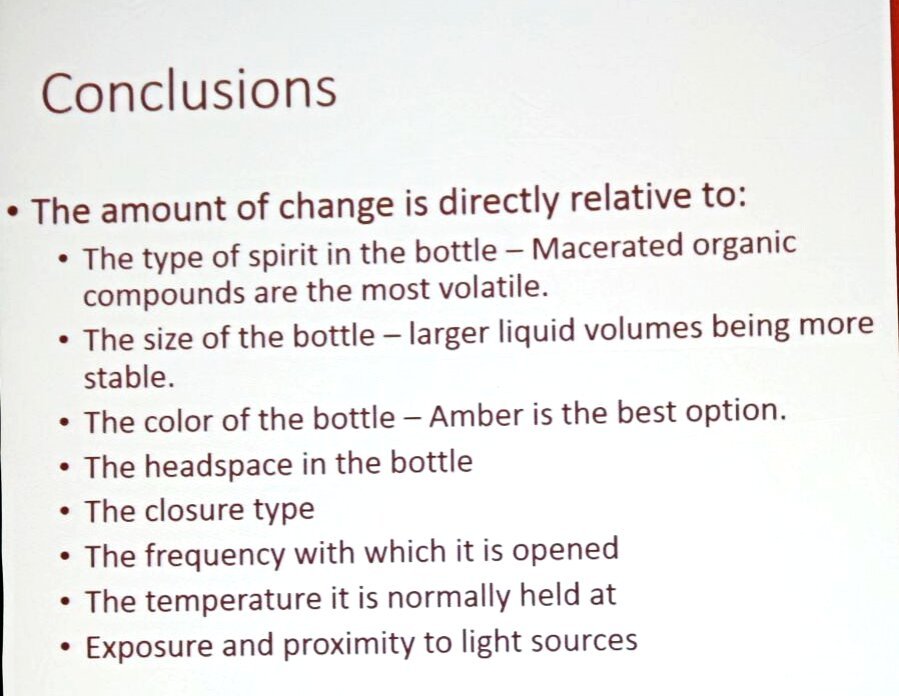

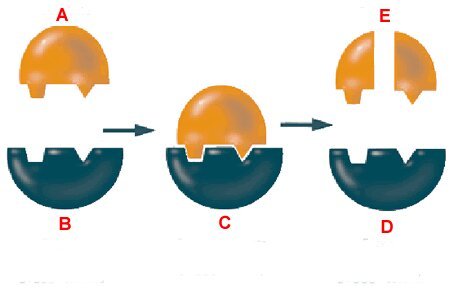

The most important information is on this slide:

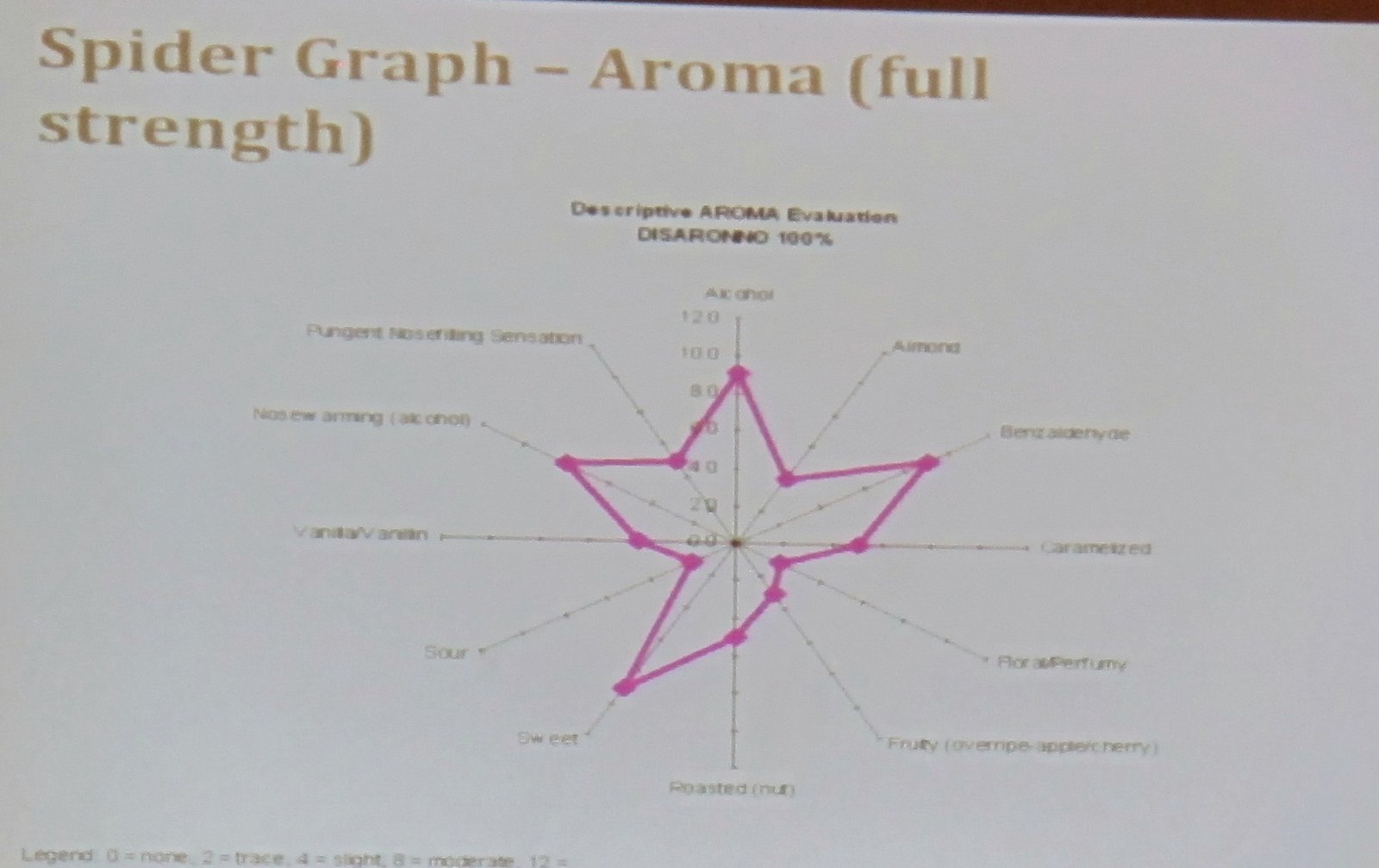

Here are a lot of notes:

Temperature: They found that for heat, degradation really occurs at 100 degrees Fahrenheit (37.8C). They tracked the temperature of bottles as they were shipped around the world to see if they ever reached that in the process of getting from the distillery to the store, and found that when it happened, which was unusual, it was in the process of getting from the truck to the boat – on the docks- so they put in place some systems to prevent that for their most temperature-sensitive products.

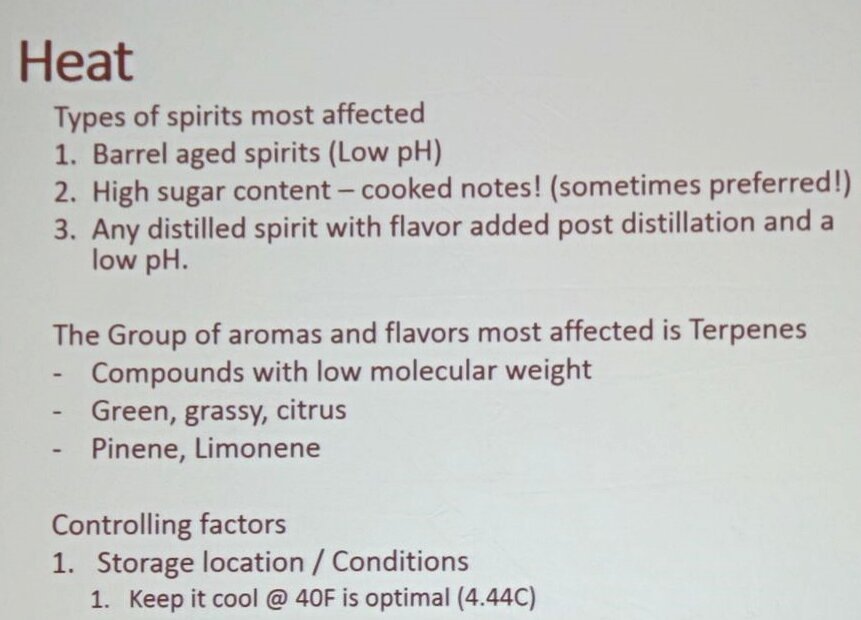

Temperature: They found that for heat, degradation really occurs at 100 degrees Fahrenheit (37.8C). They tracked the temperature of bottles as they were shipped around the world to see if they ever reached that in the process of getting from the distillery to the store, and found that when it happened, which was unusual, it was in the process of getting from the truck to the boat – on the docks- so they put in place some systems to prevent that for their most temperature-sensitive products. - Heat accelerates aging processes including oxidation, evaporation, adds cooked fruit notes to high sugar content liqueurs, affects the flavor of flavored spirits with low pH, so that's particularly citrus flavors.

- 40F (4.44C) is the optimal temperature at which to store spirits

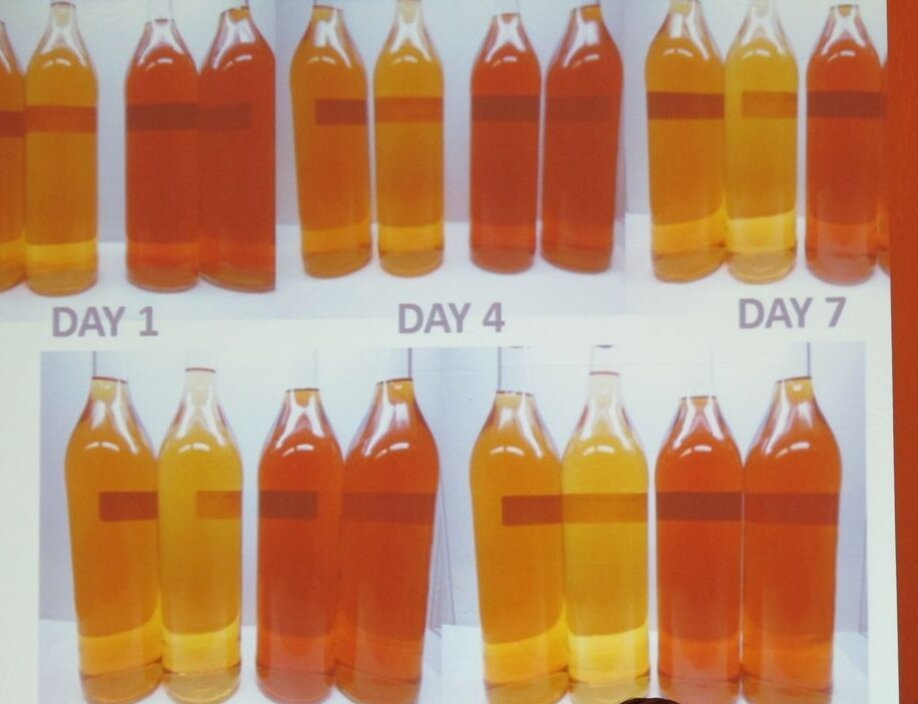

Light impacts spirits too, not just by adding heat. Aged spirits like bourbon and scotch can lose a significant amount of their color (which impacts our perception of their flavor).

Light impacts spirits too, not just by adding heat. Aged spirits like bourbon and scotch can lose a significant amount of their color (which impacts our perception of their flavor). - Light effects are impacted by bottle color (amber will have the least impact), bottles with more glass exposed (so Angostura bitters with its oversized label would be less impacted than a clear, printed bottle), the type of light source (direct sunlight, LED, fluorescent light) though it's not an easy determination of which is the worst (sunlight is really bad though) because it's the combination of the light's frequency and wavelength, and proximity to the light source.

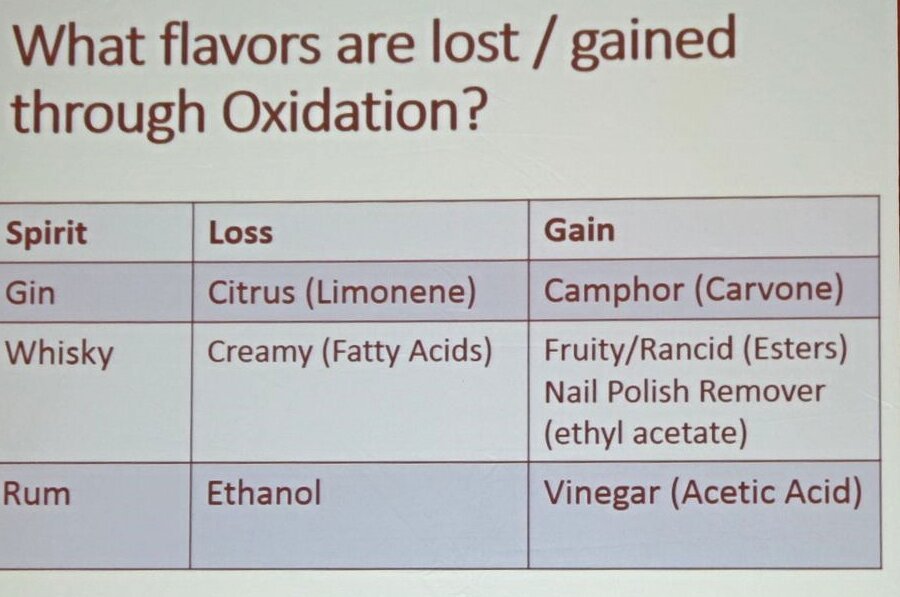

Oxidation changes flavor: Acetaldehyde from oxidation reaction can be good in small quantities – adds fruity aromas; but in larger quantities it transforms in acetic acid (vinegar). Gin loses citrus flavor and gains "moth balls" flavor. Whisky loses its creamy fatty acids, gains fruity but then rancid and nail polish remover flavors. Rum gains vinegar aromas.

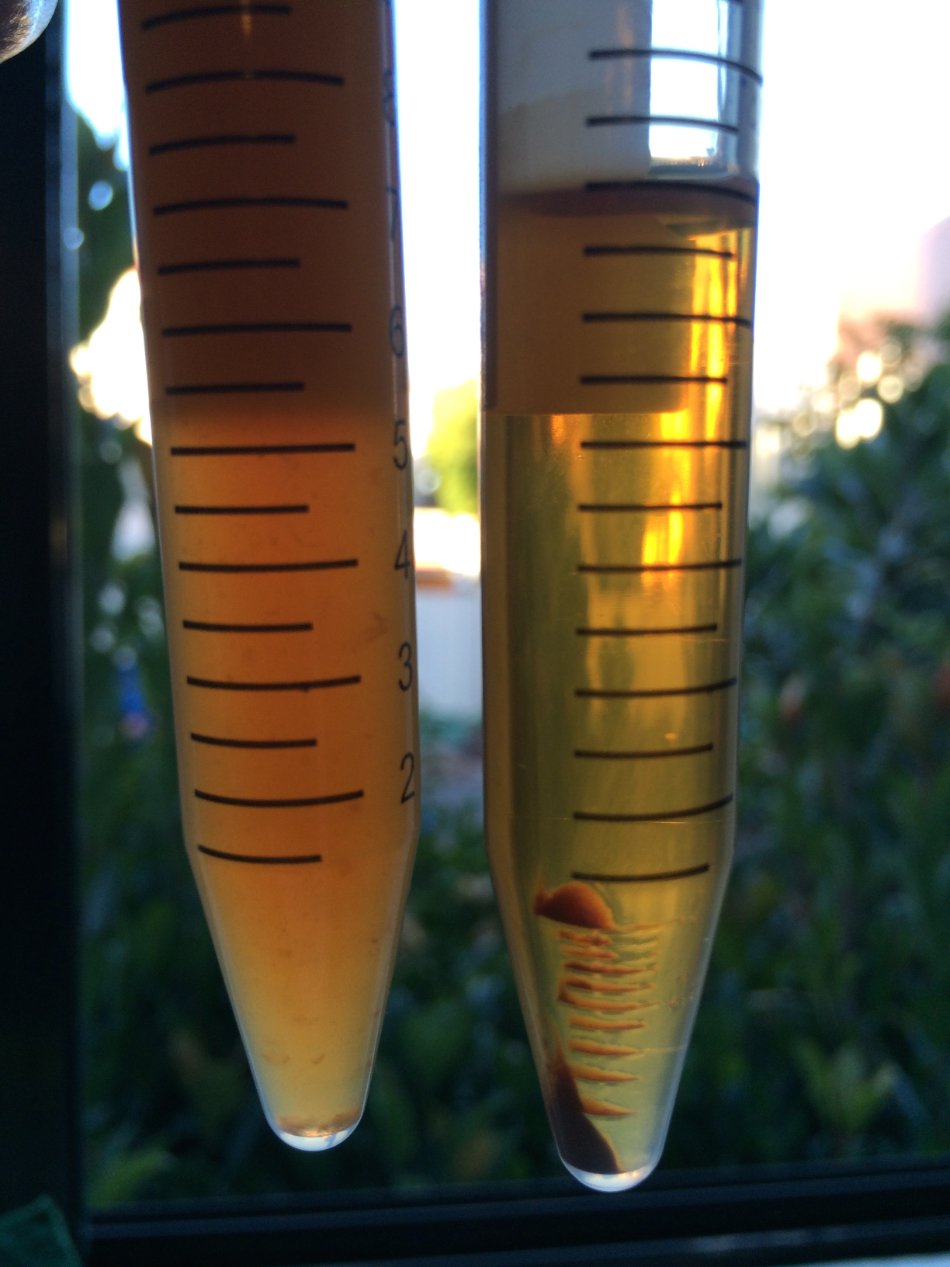

Oxidation changes flavor: Acetaldehyde from oxidation reaction can be good in small quantities – adds fruity aromas; but in larger quantities it transforms in acetic acid (vinegar). Gin loses citrus flavor and gains "moth balls" flavor. Whisky loses its creamy fatty acids, gains fruity but then rancid and nail polish remover flavors. Rum gains vinegar aromas. - Oxidation happens not just with heat and light, but also headspace in the bottle (the St. Germain bottle was cited as one particularly badly designed as you get a lot of headspace as soon as you open it), how frequently you open it (as that changes the equilibrium in the bottle- each time the air above the liquid gets exchange with fresh air), the type of closure (corks allow oxidation; screw caps less); and pour spouts can have an effect even if you cap your bottles at the end of the night.

- So to reduce oxidation you should keep precious liquids in small brown bottles with screw caps rather than 1/3 empty bottles with corks.

That was just a fraction of what was shown at the seminar, but I hope it's helpful.

I cringe every time I see the back bar against the windows (in San Francisco I always think that when I see Zuni Cafe, Absinthe, my local liquor store's wine selection, and the new Black Sands, but at least it doesn't usually get that hot in SF), but hopefully they move through product quickly so that the effects are not as dramatic.

McLaren showed a lot of slides of brightly-lit LED and fluorescent-lit back bars, with particularly bad ones being when the spirits sit on a light box as that adds heat as well.

So maybe all those candlelit, brick-walled speakeasy-style back bars aren't so bad after all.