As most of you nerds already know, most of the rye whiskey produced in the US is made at MGP Ingredients, aka Midwest Grain Products. They also make a ton of bourbon and neutral spirit used for vodka and gin. These products are fermented and distilled on site, aged on site or elsewhere, and bottled up as a zillion different brands on the marketplace.

Now in the past few years, MGP has begun to release a range of their own products. Interestingly they're not all under MGP as a brand name but under various names including George Remus bourbon, Till vodka, and Rossville Union rye whiskey. The press trip I took to the distillery was more about introducing these products to the world than the various client brands made here, but naturally that was of interest too.

History and Products

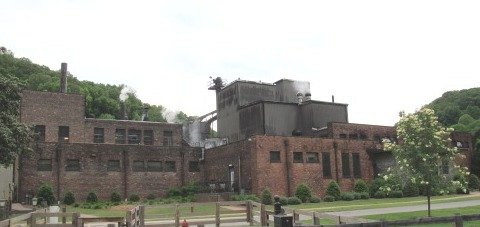

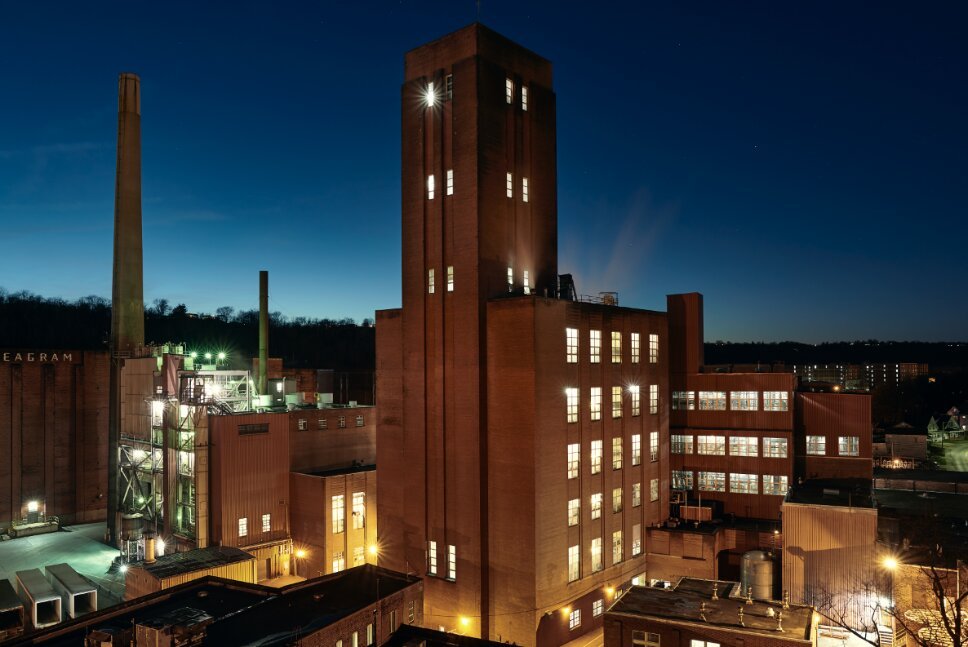

The distillery was officially founded in 1847 by George Ross as Rossville Distillery, though they've found evidence that there has been distilling on the site going back to at least 1808. In 1933 at the end of Prohibition, the distillery was purchased by Seagram and run by the company until 2001. The company was sold to Pernod-Ricard and owned by them until 2007, when it was purchased by MGP.

MGP itself is a company founded in 1941 to make high-test alcohol for torpedos to support the war effort. They actually own two distilleries though we only hear about this one.

At the Lawrenceburg distillery (outside Cincinnati but on the border of Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana) they mostly produce the aged products – whiskies- though they also do some gin and neutral spirits. The other distillery, located in Atchison, Kansas (the site of the company headquarters where it was founded) distills neutral spirits and makes gin.

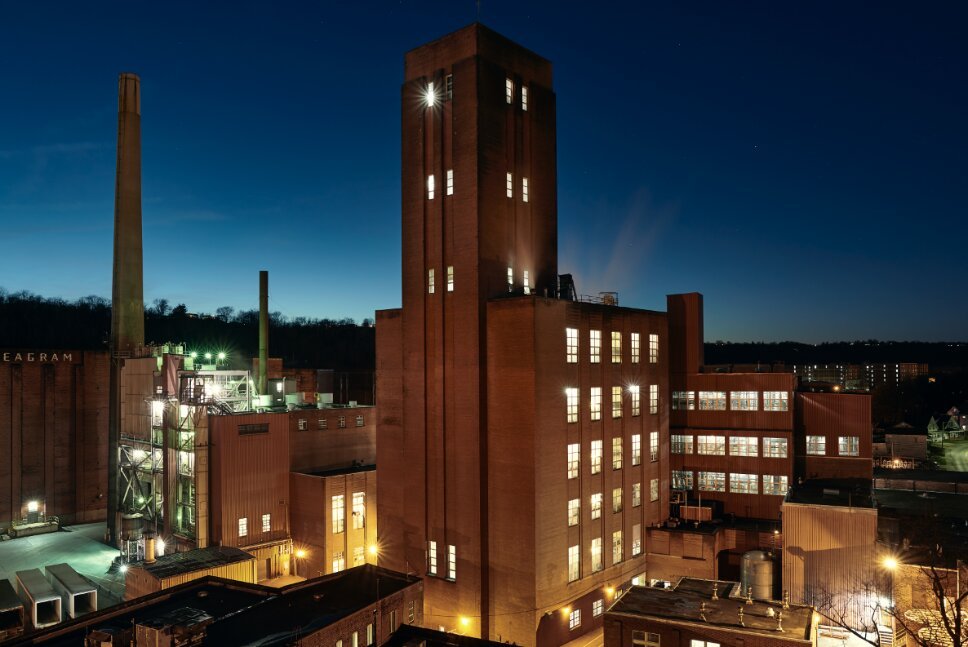

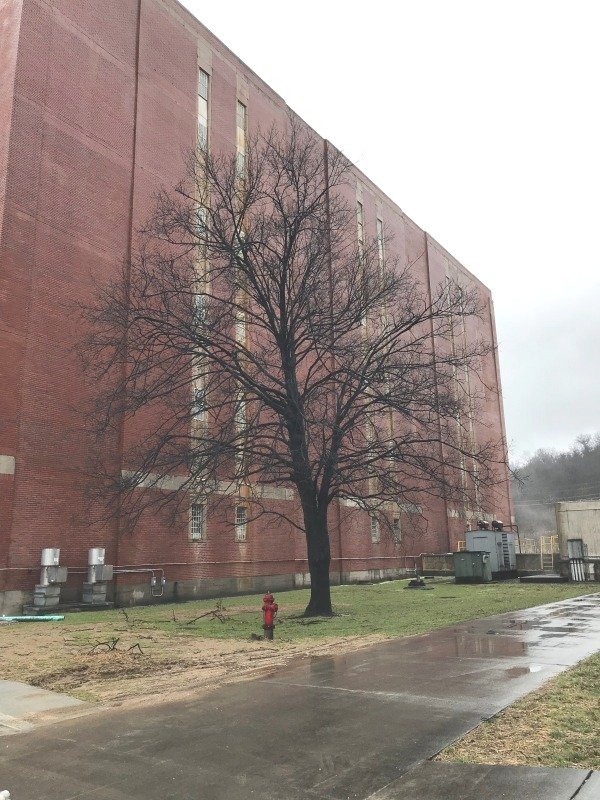

(The Lawrenceburg distillery, pics from MGP)

(The Lawrenceburg distillery, pics from MGP)

(The Atchison distillery that I did not visit. Pic from MGP.)

(The Atchison distillery that I did not visit. Pic from MGP.)

Of all the products (listed here), the most well-known and popular that they sell to various brands are the:

- 95% rye whiskey (a mashbill of 95% rye, 5% malted barley)

- 51% rye whiskey (51% rye, 45% corn, 4% malted barley)

- bourbon 36% rye (60% corn, 36% rye, 4% malted barley)

- bourbon 21% rye (75% corn, 21% rye, 4% malted barley)

So when you see those mashbills listed on products with various names (particular the 95% rye), there is a super good chance they were distilled at MGP.

Since they're dealing with lots and lots of grain, they also make grain products (list here), including raw ingredients for everything from pastries to pizza crust to imitation cheese.

I asked them how many mashbills they make in total. "We make a lot," came the definitive reply.

MGP Spirits

I was a bit worried that the MGP brands were just going to be the regular MGP products as all the various other brands with a different label and not have anything to say about them. Luckily there is a clear point of differentiation. When it comes to the vodka, theirs is made from wheat, when most of their clients' vodka is made from corn. But more importantly, the whiskies:

While nearly all their clients bottle whiskey that's of a single mashbill, MGP brand whiskies are all combinations of multiple mashbills. So George Remus Straight Bourbon Whiskey is a mix of the 21 and 36 percent high rye bourbons, and Rossville Union is a blend of the 95 and 51 percent rye mashbills.

This gives these products a point of differentiation from their many clients' products.

A Look Around the Distillery

The facility is a bunch of brick buildings located on one site, like a campus with no student lawns or a really big depressing orphanage. Different buildings house different parts of the operation – the grain store, fermentation room, distillery, grain dryer, barrel warehouses, etc.

The facility is not set up for tourists or photography, and basically we were able to see what we could see.

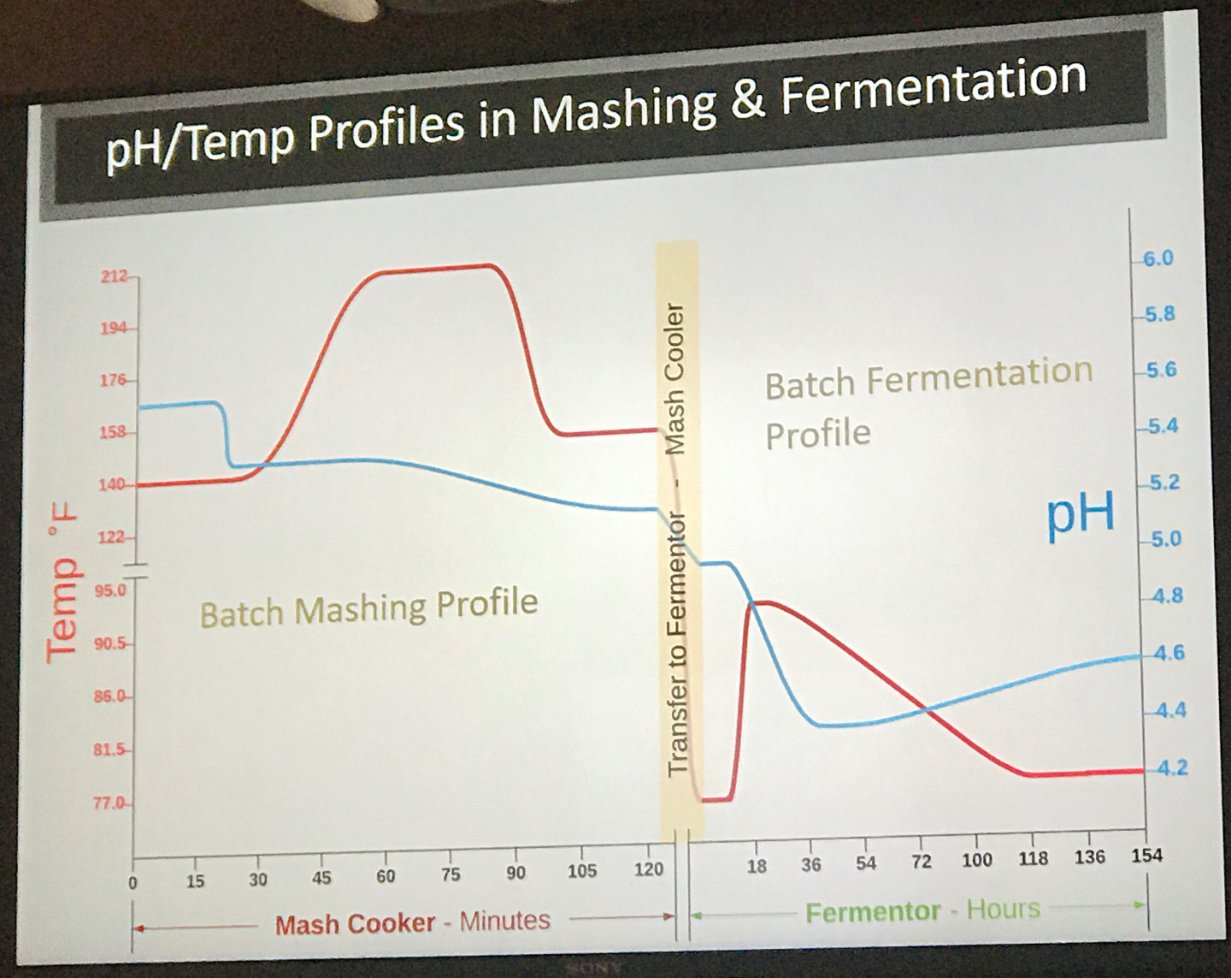

The water for the distillery comes from an aquifer, and it remains a constant 56 degrees Fahrenheit year-round. That's very convenient as in the hot summers the water is still cool to run through the condensers.

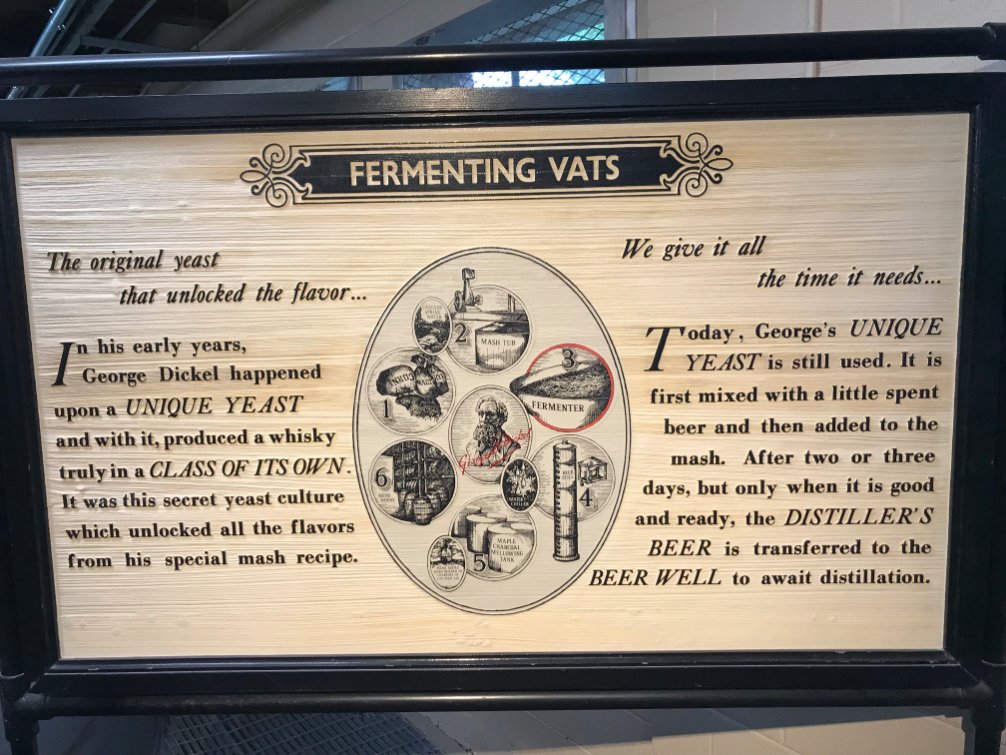

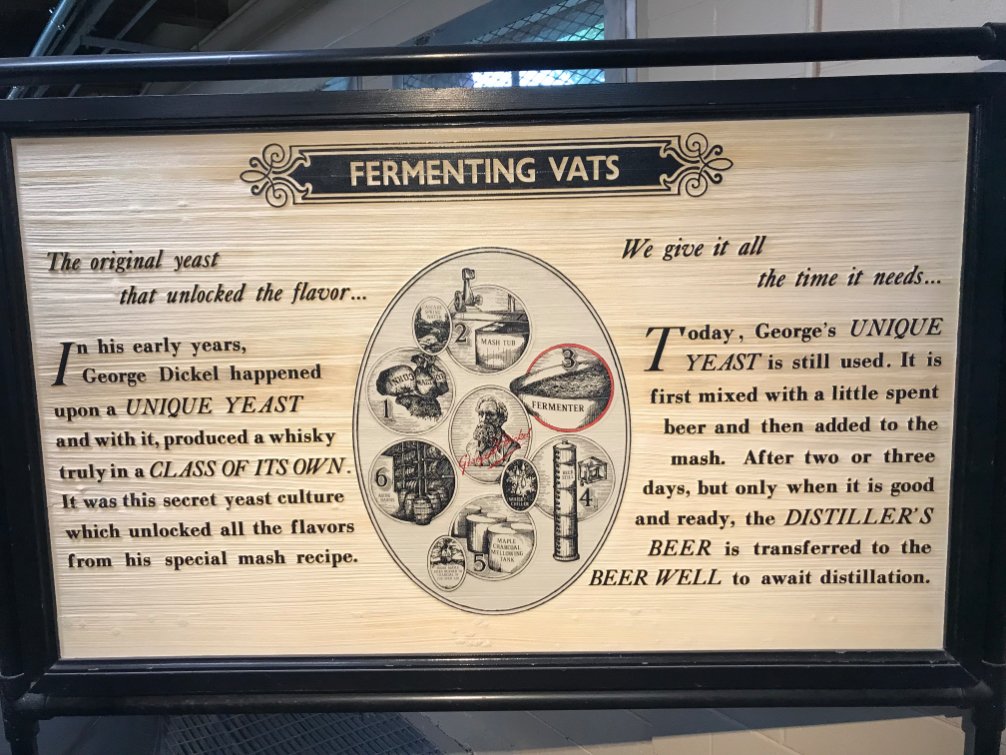

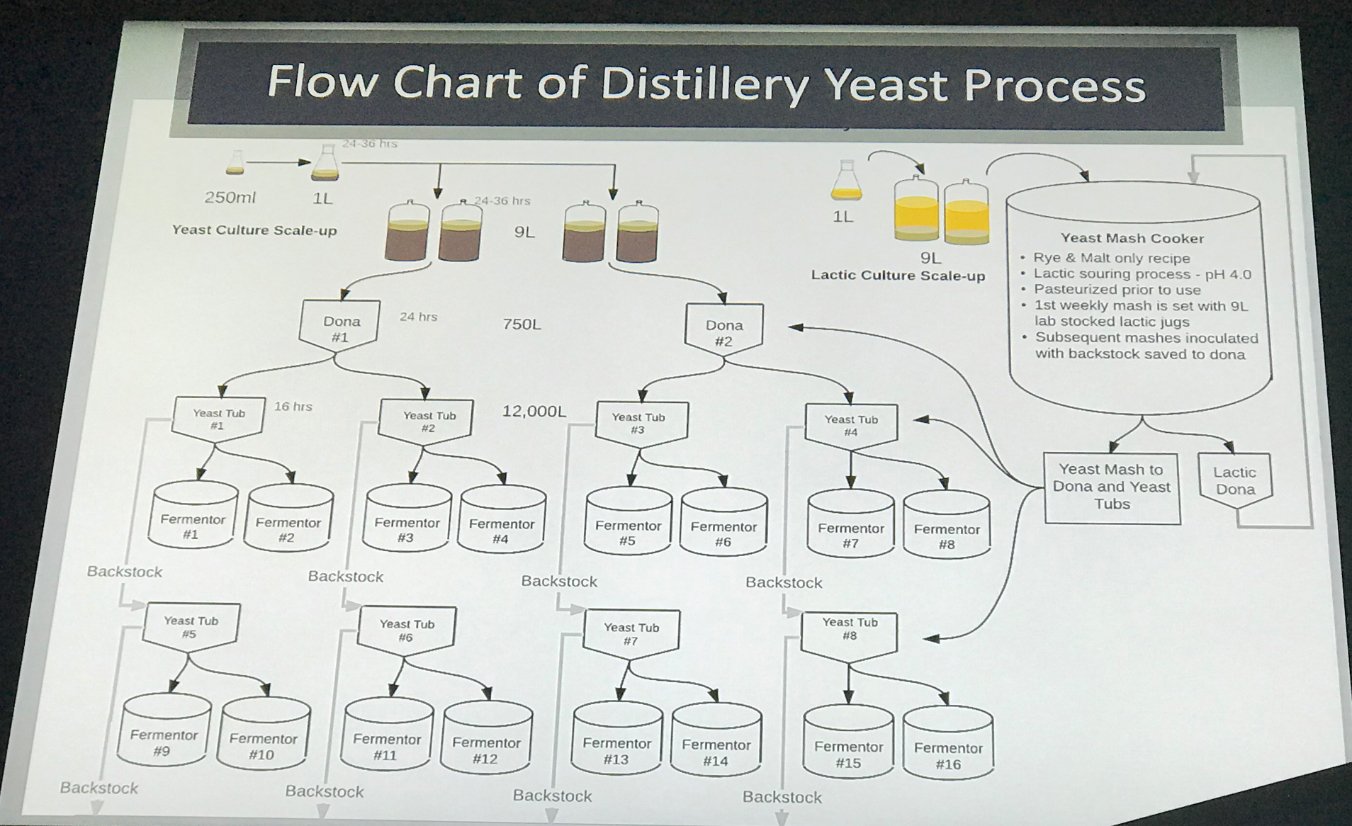

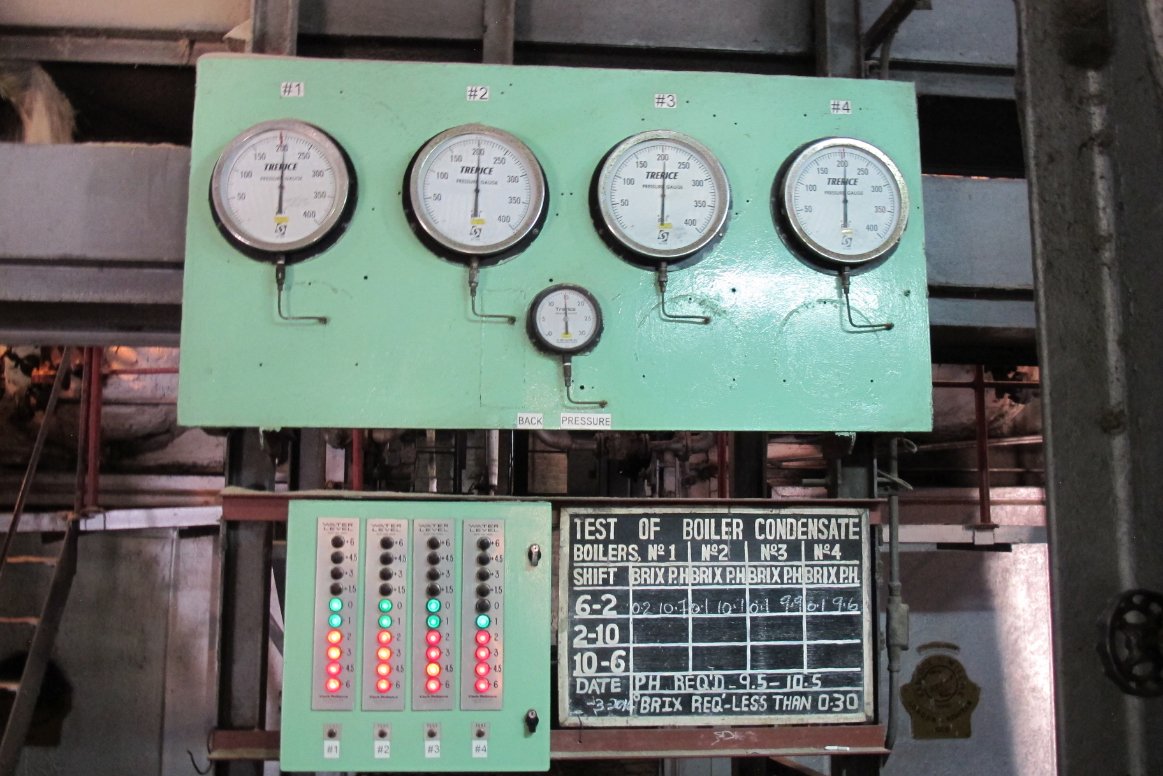

The fermentation room (there are 14, 27,000 gallon vats in this room; there is another room but I'm not sure if it's the same size). Fermentation takes about 3 days.

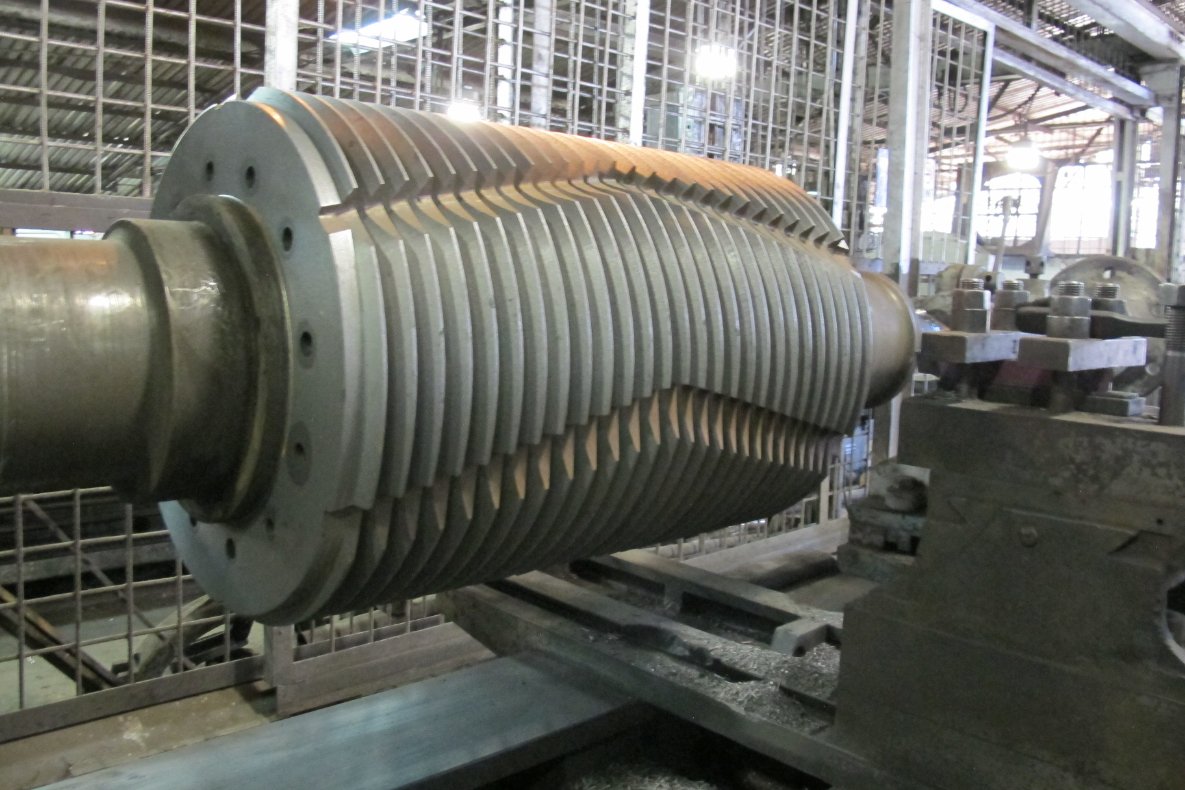

We were unable to take pictures in the distillery room, but as it passes through several floors of a building we could really only see one section of the column still and a part of the squareish gin stills anyway. In this facility there are three gin stills and two continuous column stills.

We visited one warehouse – there are seven on-site and I think 5 more elsewhere (though I'm not confident in those numbers).

This warehouse has six floors with six tiers per floor, with each floor separate from those above and below it acting as a "horizontal aging chamber." This is unlike the "vertical aging chamber" rickhouses in Kentucky where it's an open model (there's a frame on the outside but it acts as one big room) and the bottom level is cool while the top floor is super hot. The Kentucky rickhouses lose more water, as opposed to the humid ones here. They say that makes for a mellower whiskey.

Their standard barrel entry proof for whiskey is 120. We visited just the one warehouse that was racked. I inquired if their others might be palletized and the person I spoke to was evasive enough about answering that we can assume some are.

Product Specifics

So far, most of the line of MGP spirits is available in about 13 states. They're moving systematically rather than hitting the whole country at once.

Tanner's Creek whiskey, a blended bourbon, is only available in Indiana.

Eight & Sand blended whiskey is the newest product. It contains no GNS (grain neutral spirits), and no coloring. It's more than 51% bourbon bottled at 44% ABV. It's a blend of bourbon, rye, light whiskey, and corn whiskey.

"Eight and Sand" refers to a train going full-throttle (the eight) with added traction (sand on the tracks).

George Remus Bourbon is a blend of 21 and 36% rye bourbons, aged 5-6 years and bottled at 47%.

George Remus, the person, was a pharmacist turned attorney. He wrote prescriptions for medicinal whiskey during Prohibition and had his own brand of medicinal whiskey. Not only that, but he had his own medicinal whiskey trucks "hijacked" so that he could report the whiskey stolen and sell it illegally. He was known as "King of the Bootleggers" and may have been the inspiration for Jay Gatsby. He murdered his wife but was acquitted for 'temporary insanity.' More about his life here.

There is also a George Remus Reserve bottling and so far there have been two of these.

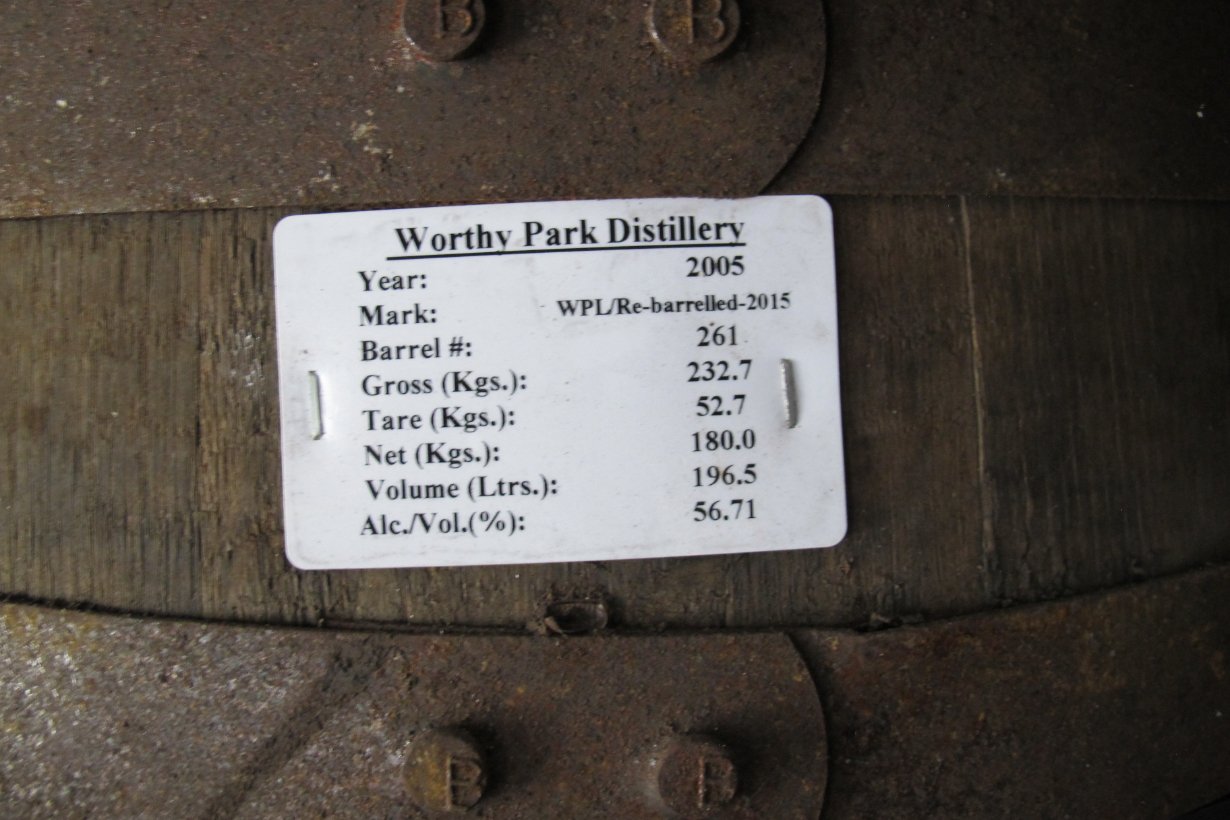

Rossville Union rye whiskey is a blend of their 51% and 95% rye whiskey mashbill whiskeys aged about 5-6 years. The standard bottling is 47% ABV.

They also sell a barrel-proof Rossville Union rye, and it's my favorite of their products. It's about the same age as their standard rye, but with a different ratio of rye mashbills. It has all that lovely pickle brine flavor but bottled at 56.3% ABV.

To make the colored ice balls I used either commercial food coloring or natural colorings like turmeric and hibiscus.

To make the colored ice balls I used either commercial food coloring or natural colorings like turmeric and hibiscus.