Months ago I started to talk about my trip to Sweden with Karlsson's vodka. I only covered how to pick potatoes so far.

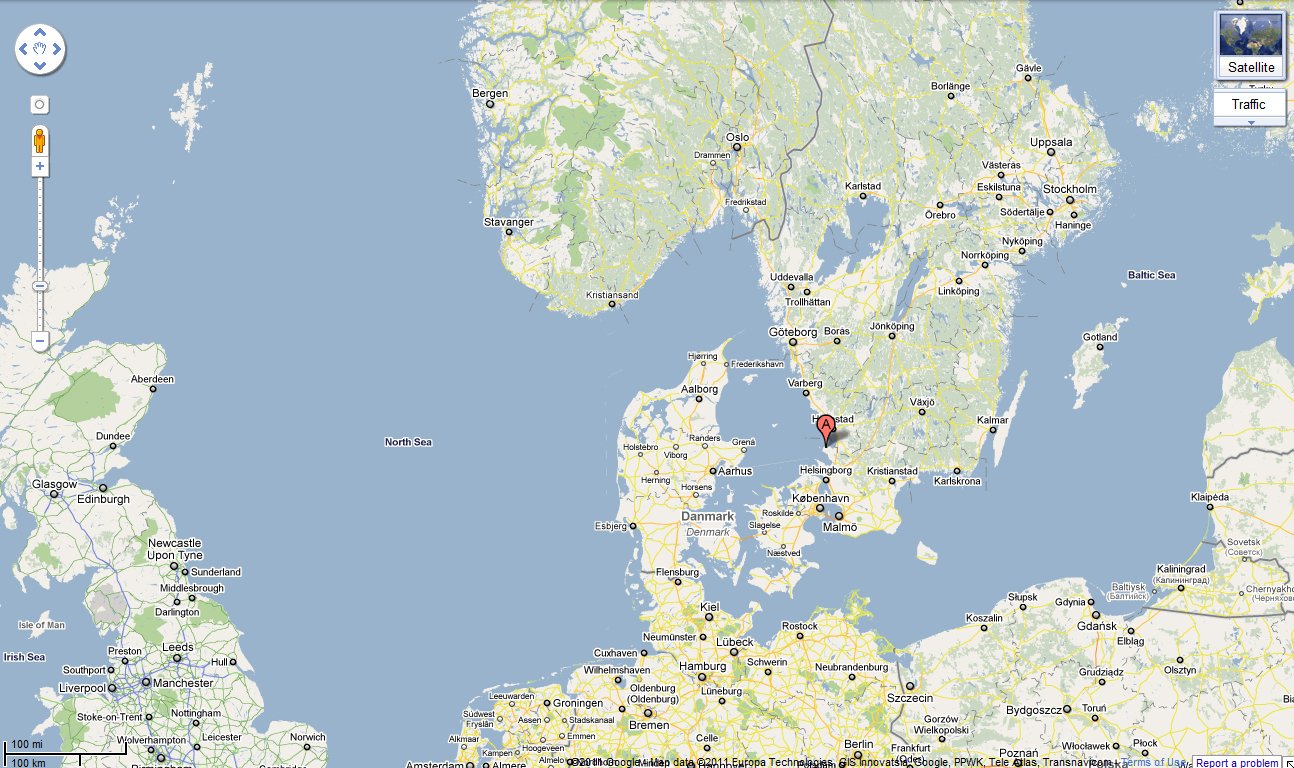

The potatoes for this vodka all come from Cape Bjare in Sweden.To get there, we drove from Copenhagen, over the relatively new bridge that connects Denmark to Sweden with Malmo on the other side, then turned North to the Cape. The town we stayed in is called Torekov.

The nearby potato farms grow little heirloom potatoes called virgin potatoes whose skin has not yet developed. For these potatoes, smaller is better, and they're served seasonally as virgin/new/fresh potatoes, which they pronounce like "freshpotatoes" so it's easy to know what they are. They are in season from May through August. I ate approximately 700 pounds of them while on the trip.

Karlsson's doesn't necessarily distill the smallest ones, but instead the larger ones that are less desirable for eating. They're still relatively tiny compared to the giant American Russets. Virgin potatoes don't have a ton of starch in them (which will be converted to sugar, which can then be distilled into vodka) but they have a lot of flavor. It takes several times more of these potatoes to make vodka it does the American kind.

In a truly unusual move for vodka, the potato farmers who contribute to the blend are all minor shareholders in Karlsson's vodka.

The Blend

In the development of the blend that would become Karlsson's Gold, they initially distilled 20 different types of potatoes. The current blend of Karlsson's Gold uses seven. At the moment Karlsson's doesn't have their own distillery but uses a few others. All of them are single column stills.

They specify the distillation parameters (there is a minimum distillation proof to be considered vodka) and then get the liquid at the end.

While most brands of vodka emphasize their distillation and filtration technology, Karlsson's focuses on the blend. They recognize that ever year's distillation is different so they worry about it afterward.

We tasted several distillations of individual varietals including Solist and Old Swedish Red (Gammel Svensk Röd). We even tried several different years of Solist potatoes (the main component in the blend) from 2004, 2005, and 2006.

These vintages tasted very different from one another, from bitter and tangy to sweet and honeyed. It's hard to say if the potatoes vary that much year-to-year, or if they were just getting better at distilling them with passing years. The Old Swedish Red potato distillate is insane- it smells like the sea and reminded me of washed potato skins.

Karlsson's is a blend of 7 potato varietals and to me tastes of chocolate, caramel, and dusty chocolate-pecan, with a scent texture (my made-up term) is the dustiness of Red Vines when you first open the package.

Making Vodka

To get from potatoes to vodka, they first mush up the potatoes. They don't even need to add water. They bring them up to 95 degrees Celsius, then add enzymes to break the starch into dextrins. It is then cooled to 65 degrees then another enzyme is added. Then they're ready for fermentation.

The yeast used to convert the fermentable sugars into alcohol is the same strain as an old yeast used for potato vodka production years ago. They maintain cool temperatures during the fermentation process, as this produces less methanol than it would otherwise.

They use the sour mash method of yeast propagation/fermentation. This is when you add a splash of yeast from the previous batch of fermentation to the next one. This ensures consistency between batches and probably saves raw materials as well. After fermentation, the mash is only about six percent alcohol.

A couple days later on a boat on a cruise around the Stockholm, we met Karlsson's Master Blender Börje Karlsson, who also developed Absolut vodka. He's kind of a big deal.

When blender Karlsson created Absolut, it was developed as an export product only, to get around Sweden's ban against producing vodka from anything but potatoes. It's funny that he's now bucking the trend; making potato vodka despite the trend in the other direction.

(Karlsson's served with crushed black pepper)

For a technically flavorless vodka, Karlsson's has a ton of flavor. I had some last night in a 2:1 Martini with Imbue vermouth and a dash of Angostura Orange bitters- my first vodka martini in eons.

Many vodka companies today are putting out very refined, smooth, subtle and supple products for vodka drinkers. Karlsson's is almost the opposite of that, an in-your-face, meaty vodka for people who normally dismiss the category as catering to people who don't like the taste of alcohol. There's no missing the flavor in Karlsson's.