It's a welcome exception to the hundreds of National Mimosa Day and other generic pitches about liquor I receive to get an email from someone who wants to talk technical details of production, and this post comes from one of them.

Gerald Rowland of Rowland Cellars and more relevantly Coit Spirits sent me an email teasing information about using fixatives in the recipe for his three gins that each call for tea:

Earl Grey Gin – with black tea and bergamot

Cape Gin – with fermented rooibos tea (red bush)

Caravan Gin – with tea smoked over pine needles

He wrote, "It took 12 months research on finding the correct plant based fixatives to stabilize the tea character that typically dissipates in 4-7 days. Normal gin botanical fixatives don't work."

Was I intrigued? Yes, yes I was.

Fixatives in Gin

In my various distillery visits over the years, distillers would say that certain botanicals act not so much as flavors on their own, but as fixatives to other desired botanicals' aromas.

Aaron Knoll wrote a very informative article for Distiller Magazine about fixatives in gin. I'll share a few relevant quotes:

The New Perfume Handbook describes a fixative as an “ingredient which prolongs the retention of fragrance on skin,” and is also sometimes described as “tenacity.” The other definition is summed up by The Chemistry of Fragrances as “a property of some perfume components, usually the higher boiling ones, which enables them to fix or hold back the more volatile notes so that they do not evaporate so quickly.” A fixative keeps the scent around longer. In the world of spirit production and distillation, we’re talking about the second definition.

The Perfume Handbook, published in 1992, lists 42 separate botanicals with fixative properties. Orris root and angelica, the two most often cited by gin distillers as being fixatives, are both present; however, so are some other common gin ingredients, such as coriander and woodruff that are rarely—if ever—granted that status.

The article concludes:

The literature on the topic of fixatives suggests that the effect in spirits and gin may not be big—or even there at all.

Furthermore, even in a profession where there is a tradition of considering fixatives in the design process, perfumer Josh Meyer explains that the process is still more artistic than analytical.

Back to Coit Spirits and Gerry Rowland. He wrote, "Most gins that have tea in their recipe usually don’t advertise it on the label (some state tea, but I have to look for it and wouldn’t have known tea was used unless I was told) as the tea is unstable and progressively dominated by the other botanicals in the recipe over time."

For most of the content below I have copied and pasted and moved some stuff around from Rowland's email and our back-and-forth conversation.

Tea is in the Tails

Black & Red teas brew at 200-212F to release their flavor [just below the boiling point of water], but London dry gin distillations are usually 176-185 F [just above the boiling point of alcohol].

The tea notes in my experience will not come over unless it comes with the water late in the distillation. I have found the tea is water soluble, not alcohol soluble.

To achieve this higher wash temp you use a lower ABV wash so the temp is higher to bring the spirit over. There is a second benefit at higher wash temperature, in that there is a true Maillard reaction of the botanicals in the wash providing a complex natural sweetness so these tea gins are made without adding sugar and yet still friendly to the palate putting them in a sip-able arena.

The tea [notes] comes over late in the distillation, usually after the tails cut of most London Dry Gin recipes as the root/bark botanicals are too harsh, triggering the earlier tails cut. The solution was to break away from traditional botanicals that trigger an early tails cut so you can capture the tea notes avoiding the harsh flavored botanicals.

In other words, some botanicals of traditional gins would need to be left behind so that they didn't interfere with the tea notes in the tails cut.

Tea Fixatives in Gin

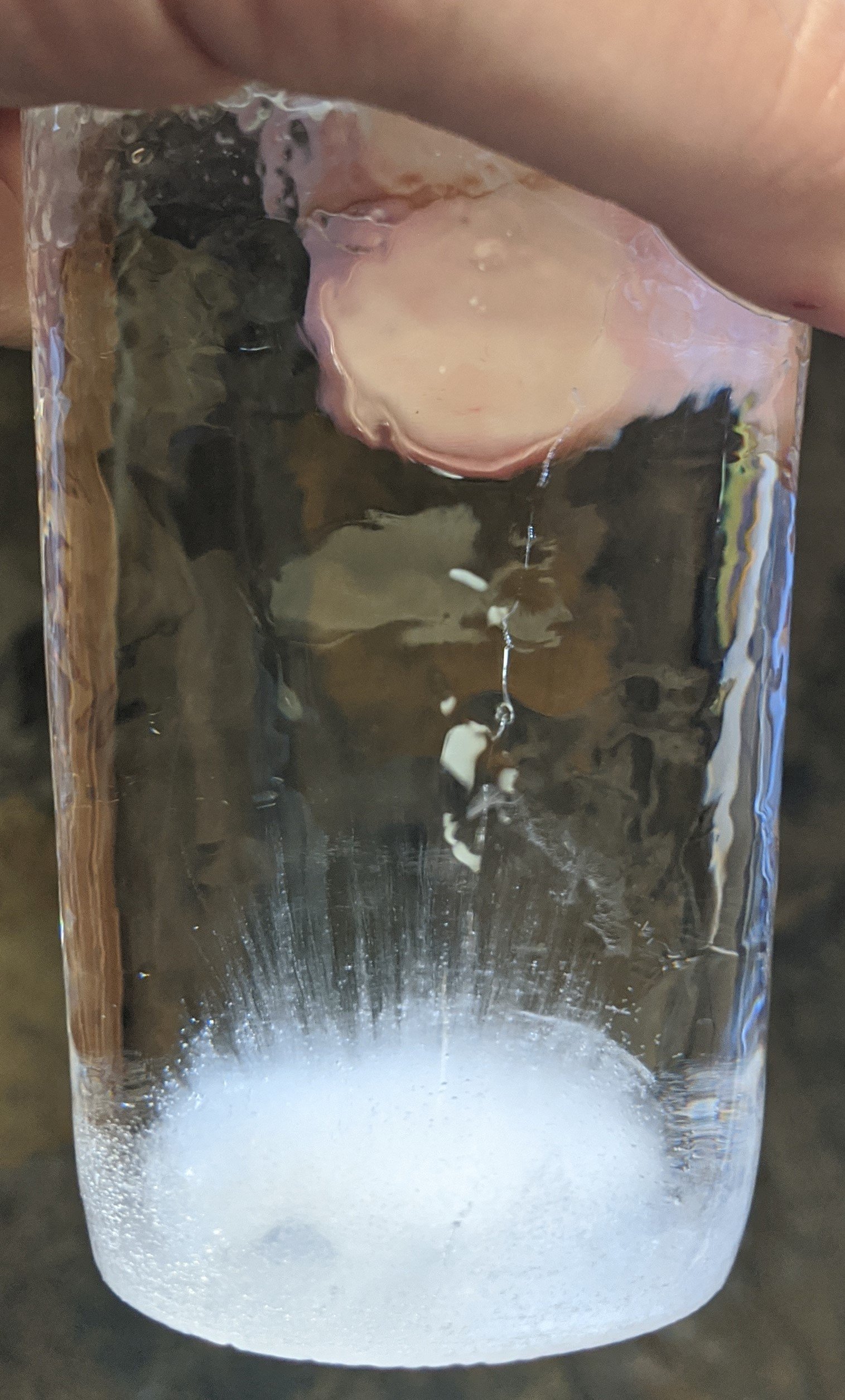

I spent as much time solving this as I did working on the recipe and the above. The tea molecules are highly charged and bind with the other botanicals. In doing so there is a polymerization of botanical molecules that provide mouthfeel but the tea definition is lost as the molecule gets too large for our sensors to perceive them. This usually takes 4-7 days and occurs if the tea is distilled or steeped.

After 4-7 days steeping you have tannin expression but the subtle character of an individual leaf is lost. This fine tea character loss occurs irrespective if you steep in water or distill, the tea character immediately starts degrading post production of the liquid and after 4-7 days lapse post production the fine tea notes are gone.

When distilling with tea the tails cut is before the tannin comes over so you capture the essence of the fine tea character note without the aggressive tannin body of the tea.

So the tails cut of the gin is between the tea flavor and the tannins, if tannins come over at all in distillation.

There is an argument I have heard that gin doesn’t need fixatives, this might be true for spirit-based aromas & flavors of London Dry gins, but for water-based aromas & flavors missed in most LDGs (London Dry Gins) because of the earlier tails cut. In my experience I find them critical for water based aromas & botanicals. People who make tea extracts find the same as does the perfume industry and why we have fixatives from a century old industry.

There may be a case that if you don’t have any water based flavors & aromas that fixatives don’t matter and this may be true for many LDGs.

For me the solution was to look to the perfume industry at fixative botanicals that the right lock & key configuration to bind onto the tea molecules active polarized sites to keep it a small and discrete molecule blocking its charged receptor sights from other botanicals. Although this creates a stable molecule larger than the tea molecule it is still small enough that we can perceive it with our sensors.

Trial and Error and Three Fixatives

When I look at a fixative being successful for Coit Gin it has needed to both protect the aroma and promote lingering.

The perfume industry uses the fixatives at much higher rates being at 100-1000 times higher than the rate I use in Coit gin to achieve tea stability. Fixatives in perfume can affect the product in 3 or more ways.

1) They can be an ingredient directly providing an aroma.

2) Provide fixative qualities to unstable aromas, protecting the aroma character.

3) Increasing the persistence intensity and lingering ability of an aroma.

As far as fixative use in Coit gin it’s for stability its strictly points 2&3 from above, protecting aroma character & increasing the longevity or persistence of the aroma.

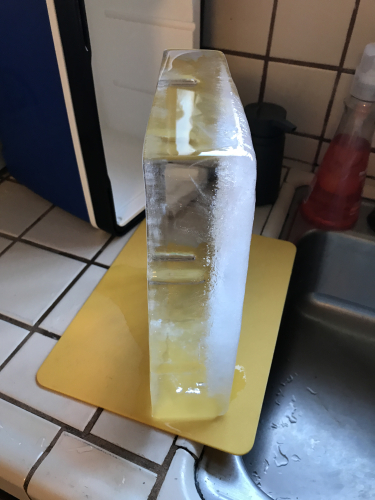

It took three fixatives botanicals to truly achieve stability and that were FDA-approved for consumption, as perfumes are topical whereas gin is internal. This took multiple parallel experiments to determine the rate of each fixative with each other.

The first fixative took stability out to 30 days at which time a small change was noted indicating a second fixative was required as more of the first fixative didn’t help. The second fixative extended the stability out to 90 days with a small change requiring a third fixative. The third fixative achieved stability.

If these experiments had been done consecutively instead of parallel it would take 1-2 decades before you would have these results. I tested many more than the 3 final plant based botanical fixatives when I went into production as no single fixative would do the job.

Once we worked out the maximum levels to prove stability we had to retest to minimum levels so the fixative botanicals did their job but did not influence the character of the recipe.

Parallels in Perfumery

I asked Rowland if he could share any examples of perfume fixatives (certain he wouldn't want to reveal the specific three used in Coit gins) so that we could have an idea of how they work. He wrote:

I provide the following selection as an example from Eden Botanicals

Note: I make no representation as to their FDA approval for use in USA.

Some Common Fixatives:

Amyris: Has a very tenacious, rich, complex odor that quickly fades out to a weak woody-balsamic scent, but is still a well-known fixative; it finds extensive application as a mild blender in numerous types of perfumes and blends well with lavandin, oakmoss, citronella, rose, Virginia cedarwood, etc.

Clary Sage: Has an herbal-sweet, nut-like fragrance with unusual tenacity; somewhat heavy with a balsamic, ambergris-like dryout reminiscent of tobacco, sweet hay, and tea leaves. An excellent fixative that can be used with perfumes of a more delicate bouquet, and with bergamot, cedarwood, citronella, cognac, cypress, geranium, frankincense, grapefruit, jasmine, juniper, labdanum, lavender, lime, and sandalwood.

Liquidambar (Styrax): Has a very rich, sweet-balsamic, faintly floral, somewhat spicy aroma, with a peculiar styrene topnote and resinous, animalic, amber-like undertones; to be used most sparingly and has excellent fixative qualities. An important element in lilac, narcissus, jonquil, hyacinth, jasmine, tuberose, and wisteria bases; it also blends well with ylang-ylang, rose, lavender, carnation, violet, cassie and spice oils. Benign solvent (ethanol) extracted Resinoid.

Oakmoss: Has a heavy, rich earthy-mossy, bark-like and extremely tenacious fragrance with a high fixative value; blends well with virtually all other oils, including lavender and ylang-ylang. Used to lend body and rich natural undertones to all perfume types.

The Choice of Fixatives for Coit Gins

On the brand's website, they list that there are 10 botanicals in the Earl Grey gin. I asked if the three final fixatives were counted among them.

The fixative botanicals are counted separate as they are at so low rates and don’t contribute flavor. My mindset was when I provide the botanical number it is about botanicals that provide the flavor and you could identify in the gin spirit.

I asked if the fixatives in Coit gins are detectable flavors, or if they're purely functional.

It took many months once finding the 3 to achieve the absolute minimum required of each when working in conjunction with each other.

At these low levels if I increase a fixative botanical rate I can see a change in expression of the tea notes but cannot pick the characteristic of the fixative itself. So the rates at these low levels are very critical. Different rates will have different effects. Fixatives are very dynamic on their rate of use effect as to protecting the aroma, persistence of the aroma and subtly influencing the aroma it is working on to swing it from a slightly savory floral note to a slightly sweeter floral note.

All 3 fixatives originate from plants i.e. root, leaf, flower, bark, stem. I also tested many highly processed plant compounds and other non-plant compounds to see what worked best, but none of the alternatives were as good as the 3 I found. In Coit’s case I was fortunate with the 3 that I found, were all of plant origin and in alignment of my mindset of a natural, vegan friendly product.

I didn't get the vegan-friendly thing until I later read the fixative article in Distiller magazine linked above, which states, "Throughout the history of perfume, the most important fixatives have been heavy, animal-derived products. Musk from civets and ambergris from whales are among those derived from fauna, however, distillers tend to draw their fixative heritage from the flora side of things."

So all of that is very interesting, and nothing I'd spent much time thinking about previously. I hope you enjoyed geeking out with me.

Other Products

Worth mentioning is that Coit Spirits also has a bourbon on the market and potentially a fourth gin on the way.

The bourbon is as transparent as the gin. From the website:

Indiana Straight Bourbon Whiskey, High Rye, Four Grain, 49% ABV

Distilled and aged on site in Indiana at MGP

Unique for MGP is the 4 grain bourbon, the corn and rye provide the backbone, the wheat uplifts both aroma & flavor, and the barley harmonizes the three.

Straight Bourbon Whiskey, straight from the barrel, assembled, proofed and into the bottle. No charcoal or cold filtration. 49% ABV

And about that fourth gin we may see in the future:

I am also working on a truly indigenous gin to the Pacific Ocean and coastal Pacific Ranges of the West Coast USA. I am 2+ years into this recipe and 80% there but still working on the finish.

Some producers have a ‘local or native gin’ these usually contain botanicals that were never indigenous to their region with local but ‘introduced botanicals’ or cross bred sub species; for example a citrus developed/cross bred in Riverside so technically from the USA, but citrus as a species never existed indigenously in the USA in the first place.

So credit to those producers for being creative but it highlights the difficulty in a truly indigenous recipe that I am working as opposed to native or local.

I look forward to trying the gins (and bourbon) out now and the native gin down the line.