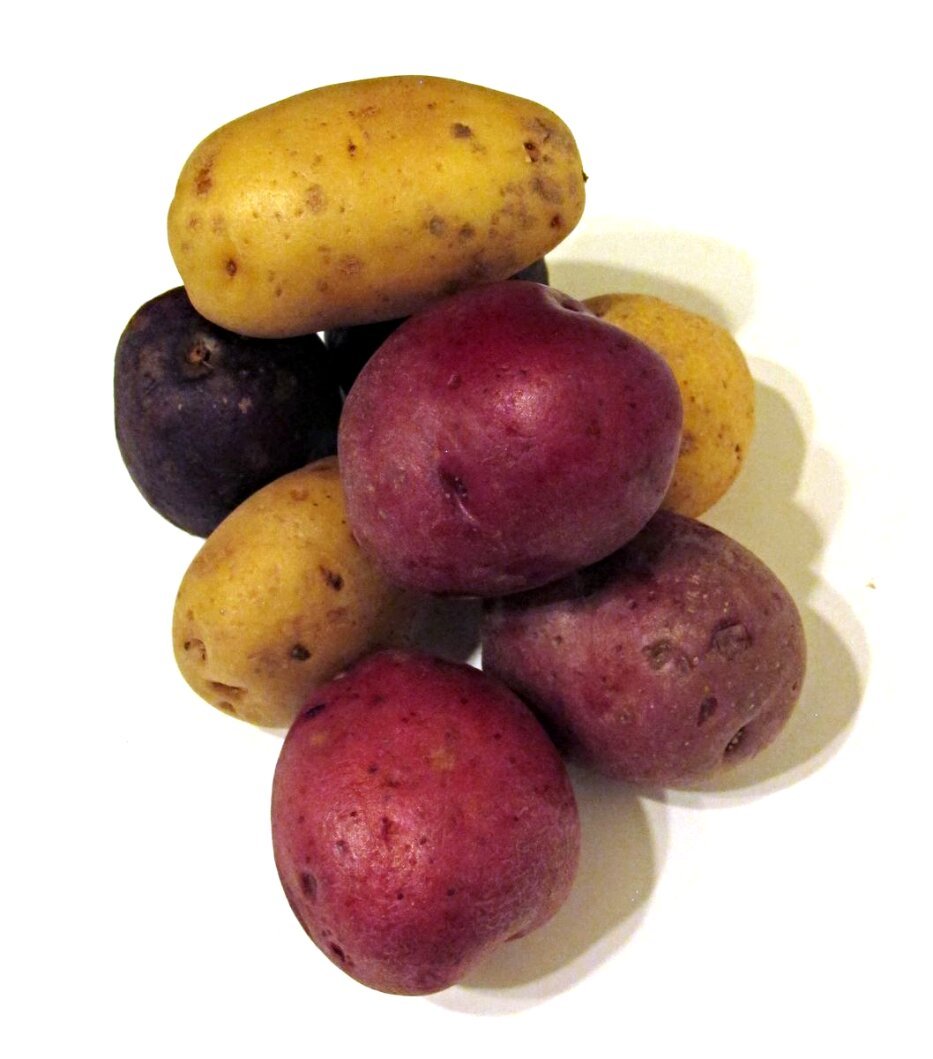

I'm researching potatoes in a project with Karlsson's Vodka.

In Sweden, vodka was originally made from grapes and grains. Then the potato took over as did a government monopoly on production (except for a little export product called Absolut). But when the country joined the European Union, that all changed.

In Sweden, vodka was originally made from grapes and grains. Then the potato took over as did a government monopoly on production (except for a little export product called Absolut). But when the country joined the European Union, that all changed.

Sweden has a strange relationship with potatoes and vodka.

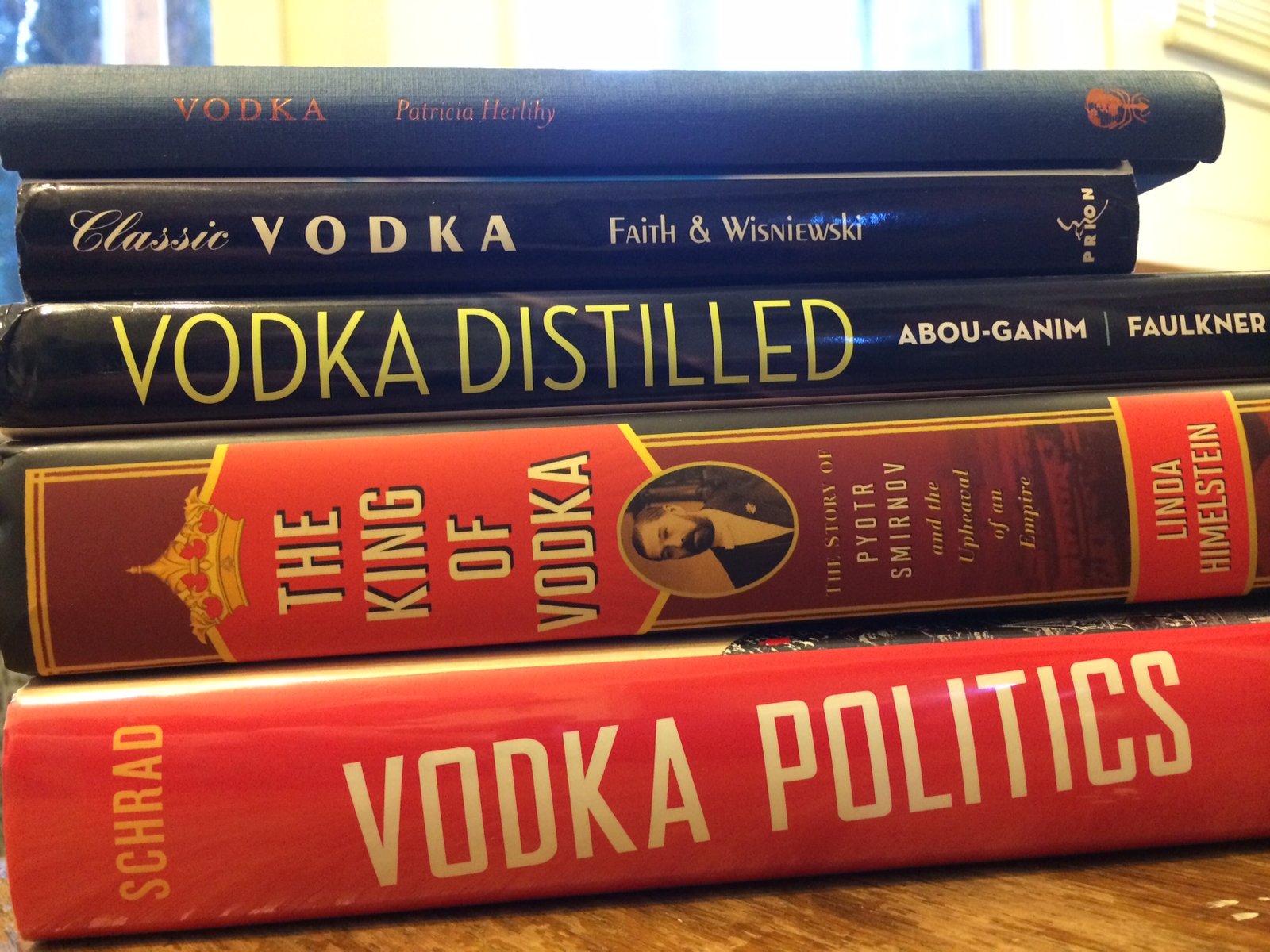

According to Nicholas Faith and Ian Wisniewski in their 1997 book Classic Vodka, distillation had reached Sweden by the 14th century, though this was used to make medicines. In the 16th century spirits became a luxury beverage, and in the 17th century they became a popular recreational drink for all classes.

Vodka in Sweden was likely made from grapes, then grain. It became a bit too popular as soon as the price came down. In 1775 a law was passed forming a state monopoly on spirits production, but this was abandoned soon after. It would come again later.

According to the book The Vodka Companion: A Connoisseur's Guide by Desmond Begg, "Potatoes, a cheaper raw material than wheat at the time, were first used in distillation in the 1790s."

With the invention of the continuous still and other technological advances, potatoes became easier to use as raw material in the early-to-mid 1800s.

The Swedish Temperance Society was founded in 1837. In 1860 home distillation was forbidden in Sweden. Throughout the mid-1800s, different cities granted exclusive rights to sell vodka to certain groups of tavern keepers. These taverns closed early at night to prevent excessive consumption, and vodka was only served with meals. Profits collected from vodka sales were reinvested in the local community, and in Vodka Politics by Mark Lawrence Schrad, the author asserts that this system was responsible for curtailing excessive consumption throughout the country.

These local city-wide companies were eventually merged into the national retailing monopoly, the Systembolaget, which is still in place today. Vodka rationing – limiting individuals to a maximum amount- continued into the 1950s.

In 1917 Vin & Sprit was formed when the state liquor company purchased the largest rectifying company, giving it a monopoly on manufacture, retail, and importation of all alcohlic beverages. This monopoly lasted until around 1995 when Sweden joined the European Union. They kept control of retailing (Systembolaget) but sold off state-owned production.

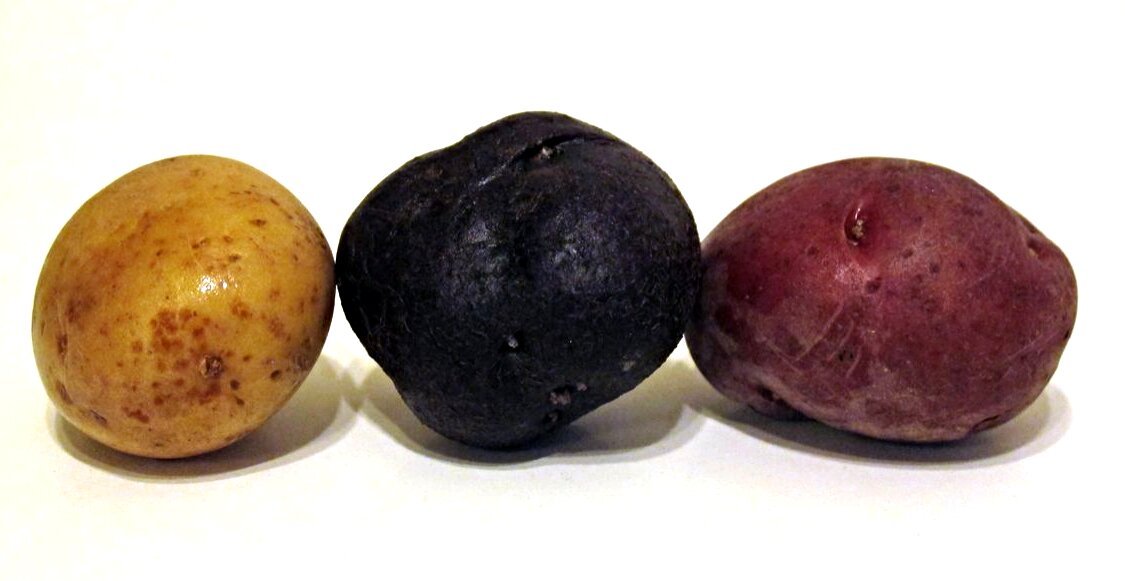

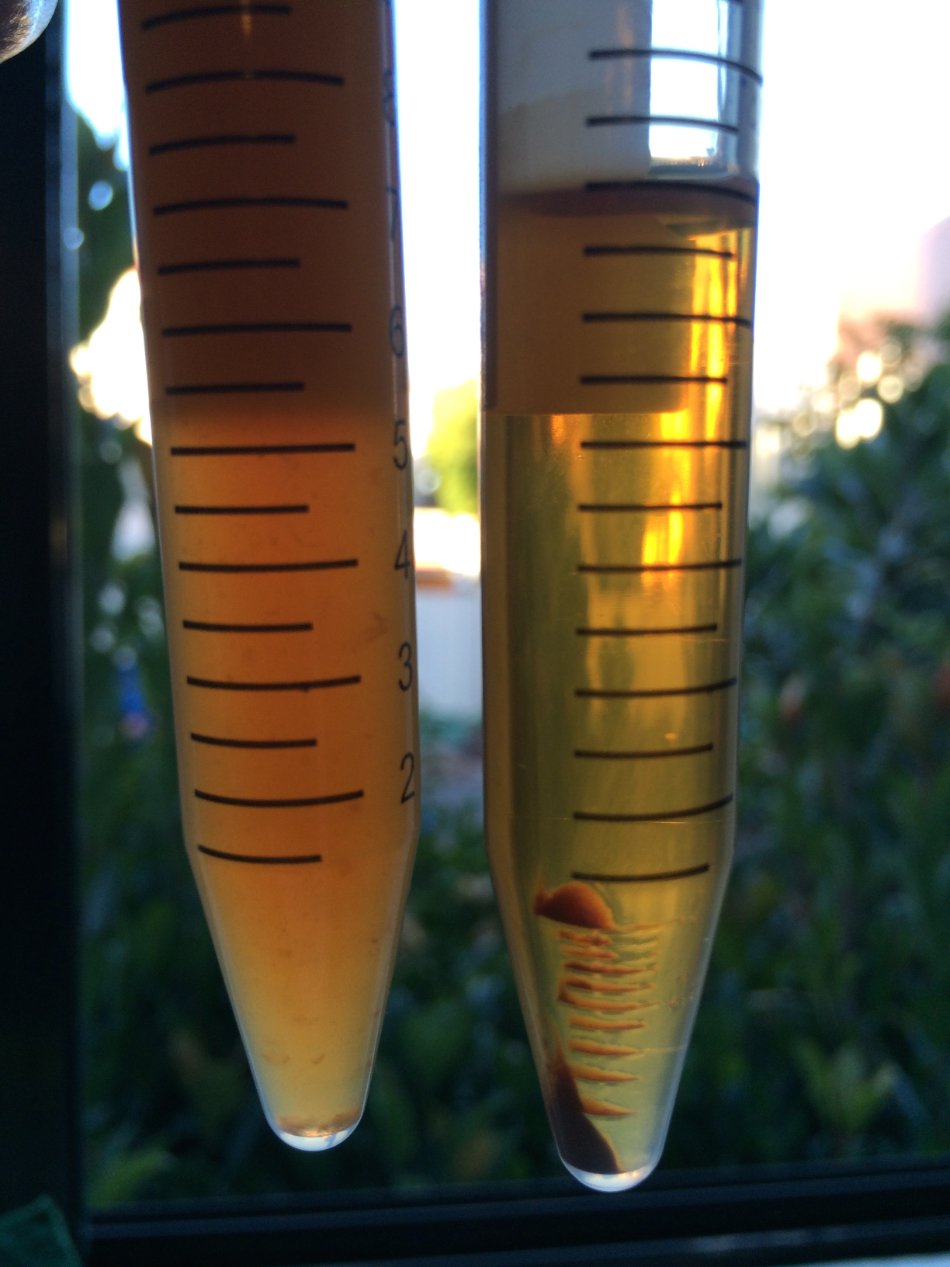

Peter Ekelund, the main creator of Karlsson's vodka, says that under V&S control all spirits were supposed to be made from potatoes as (it more like a compuslary agreement than a law). It was a farm subsidy agreement probably dating back to post-WWII. But these were ‘starch potatoes’ that had no real flavor.

That is, all vodka was made from potatoes, with one notable exception.

Absolut History

Absolut vodka was a brand dating to 1879, named for being "absolutely pure." The brand was resurected by Vin & Sprit for its centennial anniversary, and in 1979 was made from grains rather than potatoes.

According to Peter Ekelund, this was allowed because Absolut was solely an export product.

Obviously, Absolut was a huge success and in 1985 it was the largest-selling imported vodka in the USA.

But when Sweden joined the European Union they sold off V&S. Vin & Sprit was bought by Pernod-Ricard in 2008 for 5.69 billion euros.

Return to Potatoes (The Karlsson's Team)

When Absolut was created, this was a government product, so the people who created, blended, and exported the brand didn't take home a chunk of its enormous profits. But many of the same people who helped create it came back together to create Karlsson's, an heirloom potato vodka.

When Absolut was created, this was a government product, so the people who created, blended, and exported the brand didn't take home a chunk of its enormous profits. But many of the same people who helped create it came back together to create Karlsson's, an heirloom potato vodka.

The vodka is named for Börje Karlsson. He is the blender of Karlsson's and was the Head of Laboratory and Product Development of V&S Group during the development of Absolut.

The founder of the brand is Peter Ekelund, who had helped lead the launch of Absolut Vodka in North America.

The bottle designer is Hans Brindfors, the former Art Director of Carlsson & Broman who designed the Absolut bottle.

And they also reunited with Olof Tranvik, who introduced Absolut to Andy Warhol back in the day.

It's pretty cool that some of the same team who helped create the vodka that broke the mold of what Swedish vodka could be gathered to break it again in a return to potato vodka.

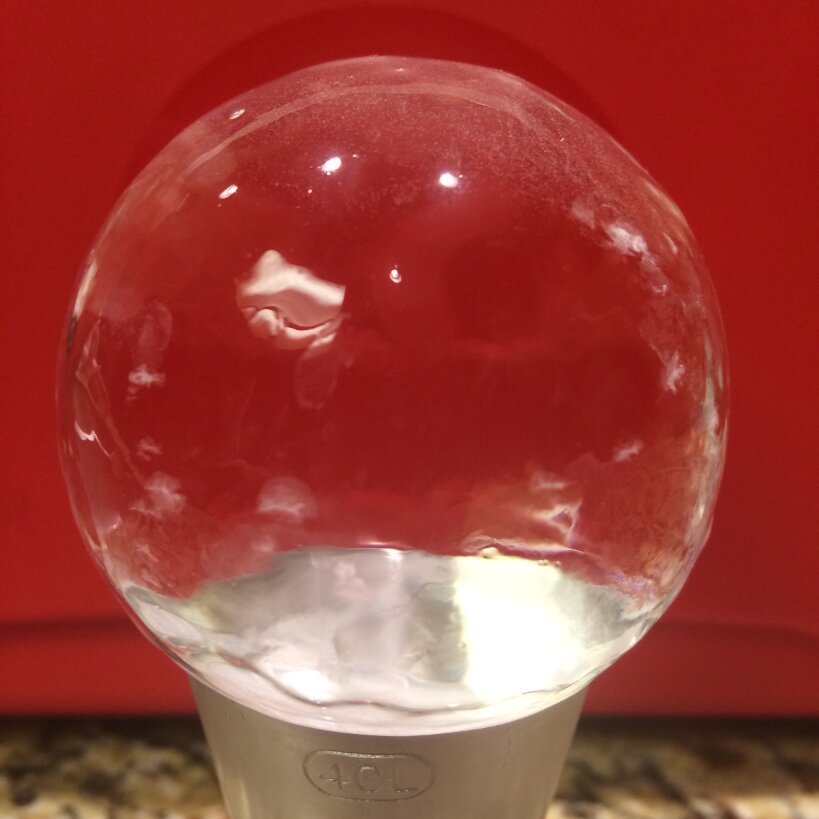

When they started making Karlssons a lot had changed since 1979: There were no distilleries left in Sweden that could distill from potatoes anymore.