In the process of making powdered liqueurs for future use, I've been trying to figure out the best method to get liquids into solids. I'll be comparing the microwave to the oven to the food dehydrator, using Campari as my first liqueur in all of them.

In the process of making powdered liqueurs for future use, I've been trying to figure out the best method to get liquids into solids. I'll be comparing the microwave to the oven to the food dehydrator, using Campari as my first liqueur in all of them.

In today's post we'll look at using the microwave. As I learned the hard way, what you don't want to do is stick a liqueur in the microwave and turn it on high. It fizzes, splatters, and burns.

So I attempted to dehydrate liqueur using a low-power setting. In the process I learned something about microwaves, or at least the microwave that I own: Lowering the power doesn't actually lower the strength of the microwave energy, it only changes the length of time it blasts that energy into your food.

So at the lowest power setting (10 on my microwave), it blasts the liqueur with microwave energy for 10 percent of the time, or for 3 or 4 out of every 30 seconds. The rest of the time it's just turning on the plate. The "defrost" setting is level 30, which should tell you how low the setting is.

The One-Shot Method

Because I don't want to stand around the microwave pressing stop and start, I tried to find the setting that would allow me to cook down a liqueur to a solid.

After several tries and lots of hot boiled Campari I determined that I couldn't microwave on any power setting higher than the lowest setting of 10. After just a few seconds the liqueur would start to boil rapidly, then it settles down in the remaining 27 seconds. However, after it cooks down nearer to the end (all the alcohol should be boiled off, but the water is still trapped in the syrup) it seems to boil faster, and overflows and splatters after only the 3-4 second heat interval.

Thus it seems that my microwave is too powerful to effectively reduce the last part of the liquid liqueur to a solid.

The closest I've come (so far) to making this effective is cooking it on the lowest power setting for 60 minutes (which reduces the volume by half, close to the final volume of syrup) then finishing the drying in the oven at 170 degrees Fahrenheit as this is low enough that the syrup doesn't boil over.

However, at least in initial experiments, it takes a very long time to bake off the final water – more than 5 hours. And in this case, I may as well just stick it in the oven at 170 degrees Fahreinheit over night.

The Babysitter Method

As the 'set it and forget it' method of programming the microwave proved ineffective, I thought I'd try the hard way. I put the same 2 ounces of Campari in the microwave and heated it for short bursts until it boiled. Then I'd stop, wait for it to settle, and hit it again. The point was to prevent overboiling and burning.

Don Lee reported success with this method, using short bursts at the beginning and end of cooking, and longer cooking in the middle.

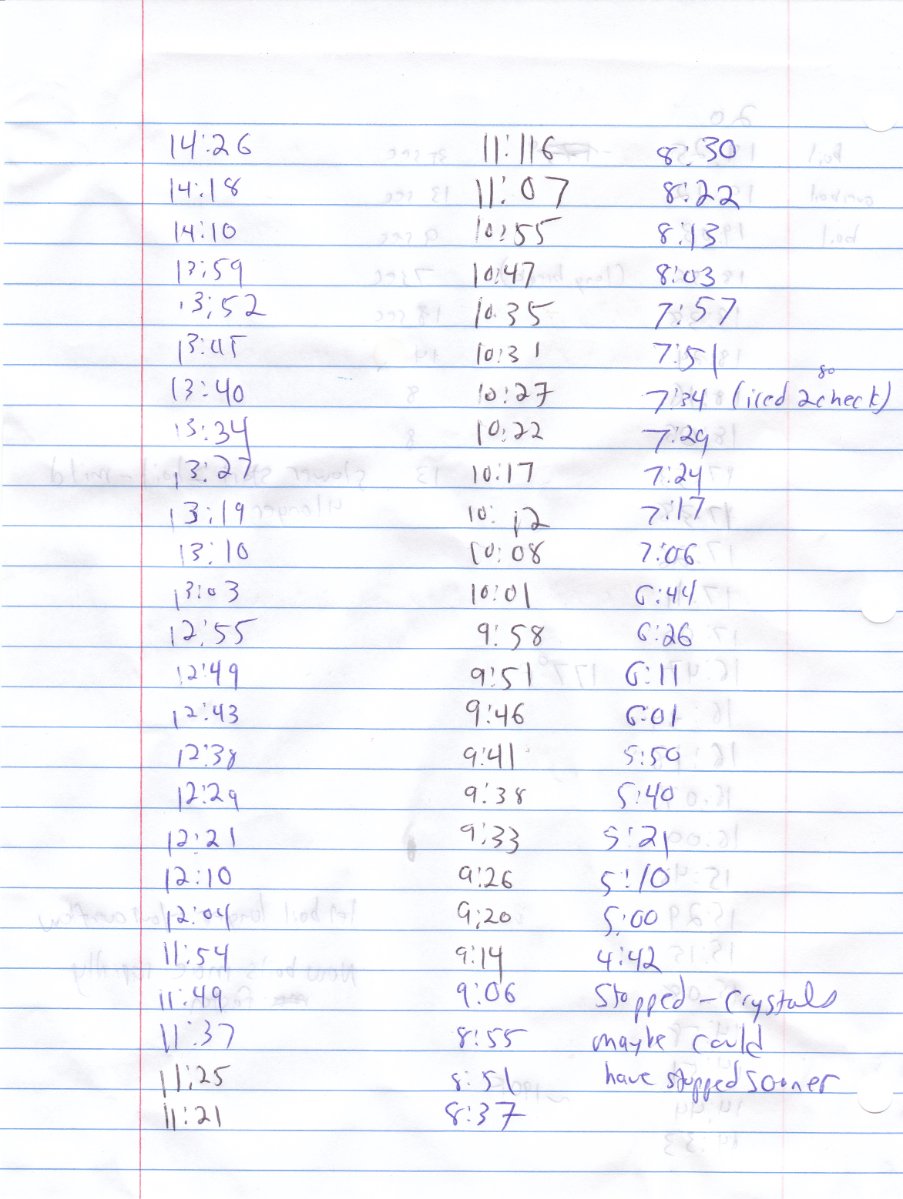

I begun with 20 minutes cooking time on the clock, then kept pausing the heating as the boil became violent. Initially I'd do it standing there babysitting the thing, but then as it was taking forever I'd send emails and such in between heating bursts, allowing it to cool more.

Unfortunately, this method allowed me no long bursts of cooking – it kept boiling over at 10 seconds maximum. More than 85 short bursts over several hours later, it finally chrystalized, though there wasn't all that much of it left.

In conclusion, with my microwave and using Campari anyway, this method is a pain in the butt and not worth the effort compared with setting the oven on a low temperature and letting it cook down overnight.

The Solid Liquids Project index is at this link.