There are no legal differences between triple sec and Curacao, only a few practical and many historical differences. In summary:

There are no legal differences between triple sec and Curacao, only a few practical and many historical differences. In summary:

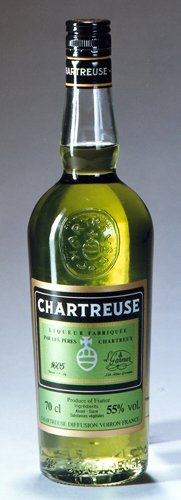

- Both triple sec and Curacao are orange-flavored liqueurs, and today’s triple secs are typically clear, while curacao is either clear or sold in a variety of colors, including blue.

- Curacao liqueur is not required to come from the island of Curacao nor use Curacao-grown oranges, and according to US law, both triple sec and curacao are simply defined as “orange flavored liqueur/cordial.”

- Some orange liqueurs including Grand Marnier use an aged brandy base, while most use a neutral spirit base.

In short, today there are no hard and fast differences between curacao and triple sec (other than curacao is sometimes colored), and bartenders should use what is best for a particular drink. But the history of how orange liqueur came to be known by these different names is interesting.

From the Caribbean to the Netherlands

"Curacao" liqueur refers to a liqueur with flavoring from oranges that grow on the island of Curacao, off the coast of Venezuela. These oranges are known as bitter oranges or Laraha oranges, with the botanical name Citrus aurantium var. curassuviensis.

These are a variety of sweet Seville oranges that changed in the arid island climate and are reputed to taste awful on their own, but the sun-dried peels of them are prized in making liqueur compared with traditional sweet oranges. Today, bitter oranges are still used in many liqueurs and some gins, though these are most often sourced from other regions including Haiti and Spain.

However the Senior & Co. company, based on Curacao since 1896, still produces curacao (in a variety of colors) made on the island with the island’s oranges. It claims to be the only brand that uses the island’s oranges.

The island of Curacao has been a Dutch island since the 1600s, and was a center of trading and commerce for The Netherlands. The dried peels of the island’s oranges made their way back to Holland where they were infused, distilled, and sweetened. The Dutch Bols company, which dates back to 1575, states that their first liqueurs were cumin, cardamom, and orange, though they don’t specify that the oranges in the first liqueur came from Curacao just yet.

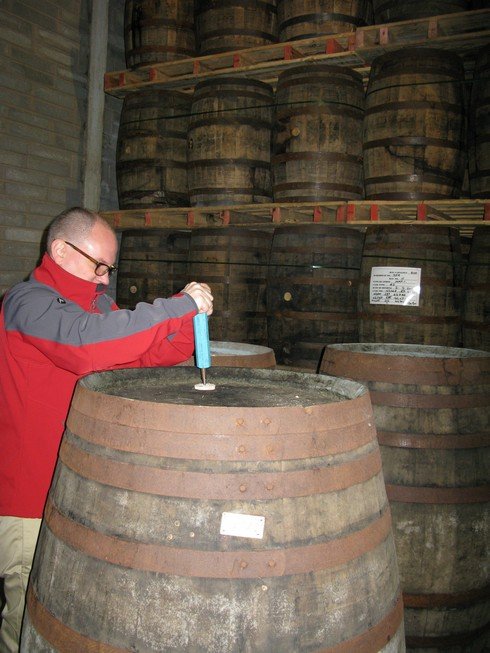

The base spirit for orange liqueurs changed many times over the years. According to Bols historian Ton Vermeulen, the earliest records of distillation in the Netherlands dating to the 1300s detail distilling grapes. The northerly climate isn’t conducive to grape-growing however, and by the end of the 16th century many distillers used distilled molasses (sugar from colonies was often refined back in the home countries, with distillable molasses as a secondary product). In the 1700s the Bols company has records of both grain alcohol and the molasses-based “sugar brandy” being used as base spirits. Grape brandy was seen as more refined, and according to Vermeulen, the “owner of Bols around 1820 would prefer to use [grape] brandy and if it was too expensive would use grain alcohol instead.”

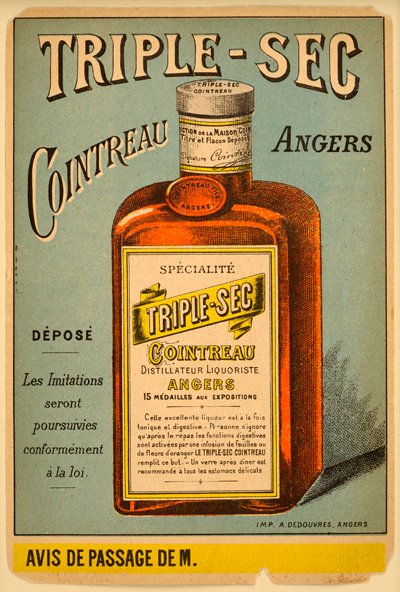

Column distillation that spread after 1830 allowed for any fermentable matter to be distilled to near neutrality and make a suitable base for liqueurs. The Netherlands and most of Europe switched to using neutral sugar beet-based spirit in the second half of the 19th century, after Napoleon heavily promoted the sugar beet industry in France. Today neutral sugar beet spirit is the base of Cointreau.

France and Triple Sec

The most famous and well-respected orange liqueurs on the market today, Grand Marnier and Cointreau, don’t come from Curacao or from the Netherlands, but from France, and it seems to be in France where Curacao liqueur evolved into triple sec liqueur.

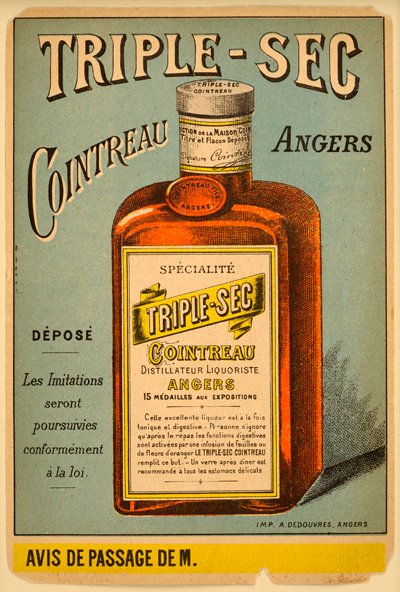

Cointreau initially produced a product called “curacao,” and then a “curacao triple sec” and then a “triple sec." According to Alfred Cointreau, the product labelling (and it seems the sweetness levels and possibly accent flavors) evolved over the years:

1859

- Curacao

- Curacao ordinaire

- Curacao Fin

- Curacao sur fin

1869

1885

Cointreau cites 1875 as the creation date of its orange liqueur, which is made with both bitter and sweet orange peels. Grand Marnier cites 1880 for its blend of cognac and orange peels. Both of these brands now shy away from the words “Curacao” and “triple sec,” on their labels.

The brand Combier claims 1835 as its creation date, with “sun-dried orange peels from the West Indies, local spices from the south of France, alcohol from France’s northwest, and secret ingredients from the Loire Valley – a formula that became the world’s first triple sec: Combier Liqueur d’Orange.”

But to what are the “triple” and “sec” referring?” The “sec” is French for “dry,” and the “triple” could point to several things.

Alexandre Gabriel, president of Cognac Ferrand, says that in conjunction with cocktail historian David Wondrich, they researched the history of triple sec and curacao and found a listing from a 1768 Dutch-French dictionary that described an infusion (without redistillation) of Curacao oranges in probably-grain spirit, but by 1808 recipes appear for redistillation of the oranges in spirit.

Gabriel’s theory is that the triple refers to three separate distillations or macerations with oranges. His Dry Curacao product is described as, “a traditional French ‘triple sec’ – three separate distillations of spices and the ‘sec’ or bitter, peels of Curacao oranges blended with brandy and Ferrand Cognac.”

By Gabriel’s definition, the ‘sec’ refers to the drier-tasting (due to bitterness) oranges from Curacao, independent of the sugar content of the liqueur. A contrary opinion comes from Andrew Willett of the blog Elemental Mixology, who makes a convincing argument that the ‘triple sec’ is a level of dryness from sugar on a scale from extra-sec, triple-sec, sec, and doux (‘sweet’).

Willett also proposes that the ‘triple’ could indicate three types of oranges: many French brands call for both bitter and sweet oranges in the recipe, plus some add an orange hydrosol (water-based orange distillate). That an early product from Grand Marnier was called Curacao Marnier Triple Orange could help support this argument. Willett concludes in another post that a “Curacao triple sec” is “Curaçao liqueur that is both triple-orange and sec.”

So “Curacao triple-sec” may refer to three distillates that include Curacao oranges, three types of oranges including Curacao in a very dry liqueur, or just a specific level of dryness from sugar of a Curacao liqueur. As mentioned, these differences and definitions are not meaningful today.

Curacao comes in many colors, but coloring of the liqueur is more traditional than one might imagine. It dates back at least to the early 1900s (when the liqueur was colored with barks) and some cocktail books including the Café Royal Cocktail Book from 1937 specify using brown, white, blue, red, and even green Curacao in various recipes.

Today, bartenders might consider each part of the liqueur in deciding which brand is appropriate for a particular cocktail: the orange flavor, the base spirit, the proof of the liqueur, and yes, the color. There’s a whole rainbow to choose from when choosing an orange liqueur.

Below Here is the Original Post that I updated with the above information. Please ignore it! It's just here for legacy purposes.

I tried to answer that question as best as I could in my recent post for FineCooking.com.

Four hundred years ago, the Dutch were some of the world’s greatest traders and, not coincidentally, great distillers. They’d preserve the spices, herbs, and fruit brought home on ships in flavored liqueurs and other spirits. Curacao was one of those liqueurs, flavored with bitter orange peels from the island of the same name. At the time, the liqueur would have had a heavy, pot-distilled brandy as its base.

Then the French came along (a couple hundred years later) and invented triple sec. The “sec” meaning “dry,” or less sweetened than the Dutch liqueur. The origin of the “triple” is still up for debate, but the two leading schools of thought are “triple distillation” versus “three times as orangey”. Triple sec was also clear, whereas curacaos were dark in color.

Today, triple secs are usually still clear (made from a base of neutral spirits), whereas curacaos may start that way and be colored orange, blue, and even red. Cointreau is probably the most recognized brand of orange liqueur in the triple sec style, and Grand Marnier, despite being French, is more in line with the Dutch curacao style as it has an aged brandy base.

Nerds: Do you think that's an accurate summation?

The full post is here, and it includes a recipe for the White Lady cocktail.

In the March issue of 7×7 Magazine, I have a story about Cocktail Snobs.

In the March issue of 7×7 Magazine, I have a story about Cocktail Snobs.